The Artifact Small Format Film Festival is an annual exhibition presented by the Calgary Society of Independent Filmmakers (CSIF) that features films produced and projected on small-format celluloid (8mm & 16mm).1“Forces of Nature”, a selection of experimental films exploring nature and the environment, will be screened on the second day of Artifact 2019. The novel and unconventional aesthetic techniques in these films create new images of the Anthropocene, opening up different ways of conceiving, understanding, and transforming the phenomenon.

The term Anthropocene was popularized in the early twenty first century by Dutch chemist Paul J. Crutzen, who proposed a new demarcation of geological time characterized by a variety of human-induced impacts to the global environment. In its scientific usage, the Anthropocene primarily relates to the increased levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere released from human activities. The Anthropocene has also taken on significance as a literary term, an evocative shorthand for the entirety of human impact on the global ecological system, often linking the destruction of the environment to political, social, and economic forces and most prominently, the intensification of capitalism.2

What can experimental films offer towards our understanding of the Anthropocene? These films do not tell straightforward, linear narratives about the Anthropocene. Instead, experimental films can be non-representational in their imagery and can mobilize representational imagery in fascinating ways. The films that will be screened on the second day of Artifact are consciously constructed as celluloid works, they foreground and reflect on the materiality of the medium. Operating outside of the commercial cinema system, these films suggest alternative ways of receiving and evaluating cinema works as we progress further into the Anthropocene.

Experimental films can engage with the Anthropocene by complicating the traditional separation between “natural” and “human”. In cinema, this distinction is often inherent to the form of landscape cinematography. The landscape shot depends upon the conception that nature exists separately from, and at the mercy of, humanity. These shots often evoke a majestic sense of scale, ensuring that nature greatly outsizes any human presence in the frame. But in the Anthropocene, it is becoming increasingly clear that the concept of “nature” cannot be separated from humanity. Nature is not a passive vessel for human projection, or a victim of human exploitation; it possesses agency and forces human responses and adaptations. By complicating the typical landscape paradigm—adjusting, distorting, or inverting it—experimental cinema can push back on essentialized, romanticized views of nature.

In the short film Catherine (2018), Marcy Saude presents traditionally-conceived landscape shots alongside more destabilizing imagery. The rural North-English farmscapes are pictured with lingering shots of grasses swaying in the wind with rolling hills in the background. This romanticism is offset by images of a young woman of South Asian descent engaging in a series of banal and bizarre tasks. Initially, she works tilling the earth of a garden and resting outdoors beneath a tree. After several minutes, she begins polishing a rock on the ground, rolls several white discs down a hill, and dismantles and transports a wooden shutter across the landscape with a wheelbarrow.

By complicating the typical landscape paradigm—adjusting, distorting, or inverting it—experimental cinema can push back on essentialized, romanticized views of nature.

The contrast between the landscape shots and Catherine’s labour suggests a disconnect between the audience’s idealized vision of the landscape and the invisible labour of people who construct the landscape. This disconnect suggests that humans are not separate from nature, because nature is always being constructed in visible and invisible ways.

The materiality of celluloid also presents new ways of conceptualizing the Anthropocene. Unlike digital images, celluloid images are physical objects which exist in the world. They can be held, and have weight and volume; they are made from various materials and processes, and have an environmental impact. In contrast, it seems that digital images do not have these qualities; they don’t have weight or a materiality to them. They seem to have no environmental impact. However, digital images require a device, made of some material, to decode them. The Anthropocene itself is a phenomenon of information—of climate data, research, global networks, and communication. In this way, it also seems paradoxically weightless. As we begin to realize the impacts we have on the planet’s systems, we become less able to understand the impact of aspects of everyday life. Celluloid can help us reconceive the Anthropocene because it can remind us that all images have some material basis.

As an object, celluloid can be hand-processed. The process involves handling the roll of film—unspooling it and transferring it though chemical baths in a dark room. The result is an image which may include deep scratches, spots, discolorations, and other perceived “defects” but which are unique and sought-after as evidence of the process. These hand-processed films can transform the act of viewing into an embodied experience where the viewer is encouraged to imagine the texture of the image on their fingers.

Nisha Platzer and Malin Schmid’s Seed (2018) is an example of hand processing used in this way. The rough, mottled, hand-processed textures complement the close-up images of plants, water, and skin, creating a sensual exploration of layered textures. Seed’s enticing aesthetic extends an invitation for its audience to go forth and sense the world. In an increasingly digital Anthropocene proliferating with more and more digital objects, the physicality of celluloid textures re-grounds one’s perception of the world in the material.

The Anthropocene is also a phenomenon fundamentally concerned with time, extrapolating past trends into future risks, and demarcating geological time as it happens. Through techniques of time lapse, double exposure, and unconventional frame rates, cinematic time can be defamiliarized from its linear flow, and re-sculpted into new forms, reflecting the various temporalities of the Anthropocene.3

In Michael Lyons’ Porto Landscape (2018), a “city symphony” film set in Porto, Portugal, various temporal devices are used to complementary effects. Lyons plays with mixing different “speeds” of time, such as the accelerated speed of picturesque cityscape time lapses and the more leisurely pace exemplified by shots tracking shadows moving across surfaces. One compelling shot at a city park mixes two different frame rates of stop motion photography resulting in a wondrous “tree breathing” effect; the trees’ shadows travel along the ground, pause as if to let the people of the city speed about, and then begin to move as the people turn into single-frame specks. The combined effect of all these techniques decenters the human element by making “characters” of the city, trees, shadows, pigeons and cats.

In removing the impact of individual humans, the film imbues the other “characters” with a sense of life and agency. Focusing on the nonhuman helps us recognize and understand the various entities (“actors” to use the terminology of Bruno Latour),4affected by and affecting the direction of the Anthropocene. An ominous feeling coalesces at the conclusion of the film as forest fire smoke blankets the city; the climate system asserts its agency over the people. Lyons reintroduces the human element in one late shot, when maintenance workers work to clear the street of soot from these fires. These people are acted upon, and must react to, these new circumstances. Lyons filmed during the 2017 Portuguese wildfires that killed 66 people, and which were the deadliest in the country’s history.5Viewed through the lens of regular, perceivable human time, it is impossible to directly attribute the event to climate change. But in the expanded time scale perceivable by instruments and mathematical models, this disaster suggests a clear trend: the increasing frequency and intensity of forest fires.6As a medium capable of representing time in different ways, cinema is a vital tool which allows us to perceive the Anthropocene differently.

Exemplifying a different approach to time, most of Kathleen Rugh’s Winter’s First Moons (2018) utilizes double and triple exposure to playfully combine footage of the moon in a free-flowing choreography of shape and light. By showing the moon at different phases, Rugh subtly, and brilliantly, evokes the indeterminate, cyclical passage of time. The film becomes an index of the meticulous, patient work required for its production, a triumph of planning and openness to chance.Winter’s First Moons (and to a certain extent, all experimental cinema) is effective because it opens the viewer up to, and prompts the viewer to understand, the artistic process. This process is informed by the (metaphorical) act of “recycling”; the moon “re-cycles” as it passes through its phases and Rugh’s process “re-cycles” by rewinding the film back to a previous point in time to re-expose it. Rugh’s one-woman process stands in stark contrast to the enormous expenditure of money, material, and labour typical of the Hollywood-style narrative. Perhaps Rugh’s film presents one small step towards outlining what it means to create ethical art in the Anthropocene; it makes us aware of the other possible ways we can construct and receive cinema.

Just as globalization and informatization accelerate the accretion of carbon in the atmosphere, digital tools accelerate the proliferation of quick editing and fast cuts. But the materiality of celluloid re-contextualizes these image flashes as products of labour, creative work, and process. The hyper-edited and quickly-cut sequences of Joshua Wisman’s Native Elegance of the Soul, or Like, Whatever (2018) and M. Woods’ Mechanomorphic Nostalgia (2018) employ rapid editing in context with their celluloid materiality. While each uses rapid editing to different effect, both films foreground the painstaking work involved in editing them.

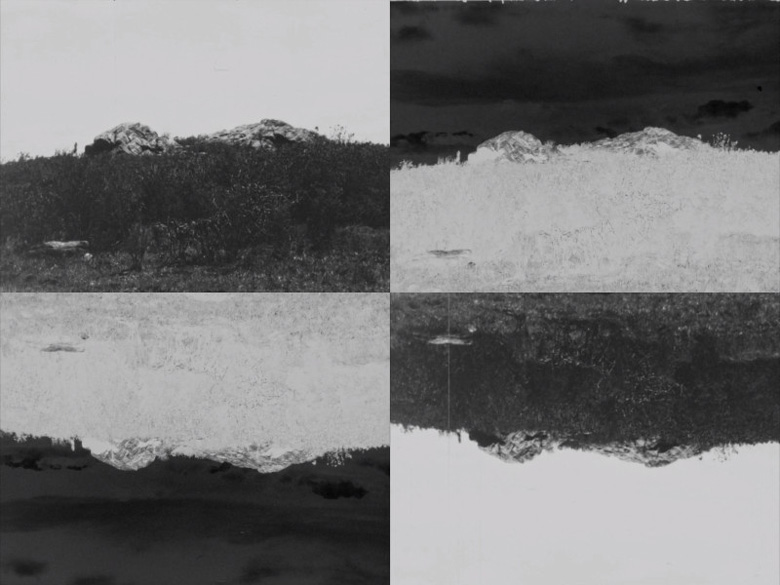

Native Elegance of the Soul, or Like, Whatever is framed as a walk through the Appalachian landscape. However, through rapid edits, such as, cutting out every second step as Wisman walks with the camera, the stereotypical tranquility of such a walk is transformed into jerky, kinetic nervousness. The film rapidly intercuts between various negative (inverted-light) and positive images of typical forest landscape imagery. In these negatives, the bright sky begins to look like the ground, and the dark ground begins to resemble the sky. Sometimes, the images are filmed upside-down, bright sky on bottom, dark forest on top, and then further inverted.

Like Catherine, Native Elegance of the Soul mobilizes the form of the landscape in order to deconstruct it, blurring and confusing the distinction between land and sky, image and inverse, up and down. A viewer paying attention to process, however, will also realize the sheer amount of labour these effects took. The intercutting of negative and positive images means the reel was processed twice, the matching image physically located in each reel twice, with each cut requiring the editor to line up each piece to attach them together with tape or glue. Wisman’s film suggests that there is pleasure gained from artistic labour and that it can be an alternative path to emotional fulfilment than the conspicuous consumption of late capitalism.

In contrast, Mechanomorphic Nostalgia stimulates violent sensory overload by projecting two reels of film simultaneously. This splits the viewer’s attention, forcing the viewer not only to consider the entire rectangle of light as a whole, but also to interpret each square’s visuals. Several techniques are further layered upon this base: scratching and colouring directly onto the film material, intercutting inverted negative imagery, double exposure of said inverted imagery, and rapid editing. Numerous images recur in the chaos: oil wells extract their fluid from of the ground, concert-goers party at a music festival, and found-footage from a racist minstrel cartoon plays out.

As a film animated by a sense of rage at “the wake of Election Day 2016”,7the labour of making this film becomes both oversaturated and de-emphasized. So much work had to go into every second of these abstract images, but the result is far too detailed to comprehend at once. The labour becomes almost banally invisible, evoking the emotional exhaustion of the Anthropocene; ecosystems are threatened with ever greater danger, all the while we become increasingly numb to proclamations of environmental collapse. We feel responsible for tackling environmental catastrophe and for paying the bills. Of all these films, Mechanomorphic Nostalgia is the most propulsive with rage as its artistic labour simulates a cathartic “acting out” at the systemic injustices propelling our Anthropocene forward. Its emotion is more potent because it’s printed on celluloid.

Sandy McLennan’s The Last Skate (2018) is a nearly opposite film, but one which is no less radical. McLennan abstracts the horizontal landscapes of a frozen Canadian lake, destabilizing this nostalgic icon of Canadiana. The film is structured around a skate on a lake, an act threatened by the reality of climate change. As we hear the scraping sound of “the last skate”, the hand-processed images look as if they’re disintegrating. The horizon lines decompose into foggy, ghastly streaks, as if receding from memory before our very eyes. Several double exposures, combining images of the horizon, the ice, and the trees together. Throughout, McLennan foregrounds his process of operating the camera while skating by continuously running the sound of his scraping skates underneath most of the imagery. The film is simple, hypnotic, and beautiful. In the program description, McLennan characterizes the spectral landscapes as a consequence of “cameras failing miserably/wonderfully in the cold”.8

Making an “environmental film” in the Anthropocene is an exercise in reconciling contradiction since filmmaking is an incredibly consumptive endeavour. Creating films expends energy in the frenzied pitch of production and in the material manufacture of its necessary components. Cameras and sensors require the extraction of common and rare earth metals. Props, set decoration, and specialized camera equipment may all be derived from petrochemicals.9Even if film aligns itself with environmental precepts or purchases carbon offsets, the specter of its environmental impact continues to influence one’s reading of it. We need to realize that art has a vital role to play in imagining alternative images of the world that reckon with the central concerns of the Anthropocene in our everyday lives. As a preeminent medium of popular art, moving images must figure into this project. Film has a role to play in decentering the human, as seen in Porto Landscape, or grounding our perception in the material, as in Seed. As Catherine and Winter’s New Moons demonstrate, film can also prompt us to think about how the aesthetic experiences around us are constructed.

Making an “environmental film” in the Anthropocene is an exercise in reconciling contradiction since filmmaking is an incredibly consumptive endeavour.

Maybe the most radical notion that The Last Skate and all process-driven cinema contributes to this project, is that of failure as a valid aesthetic strategy. Perhaps it is possible to “fail wonderfully”. The looming crises of the Anthropocene should force us to evaluate all art in some way as process-driven art. In doing so, we can find value in the pleasures of modest, small-scale artmaking, reveling in its imperfection, unexpected outcomes, and artistic failure, but also its sense of discovery, experimentation, and a pleasure taken from artistic labour-in-itself.

Experimental film, such as those screened at Artifact, might help recalibrate our hierarchies of film criticism and reception to be more receptive to values such as these, and less receptive to values of perfection, spectacle, or clarity, which often come at the price of outsized ecological impact and reinforce structural inequalities. If we can use art to recalibrate our society towards values such as kinship and community, ecology and equity, perhaps then, we can imagine a more equitable Anthropocene.

The 27th Artifact Small Format Film Festival takes place in Calgary from March 7-9, 2019. “Forces of Nature” will be screened on March 8 at 7 pm. For further details, see https://artifactfilmfestival.com/festival/

Kevin Dong is an independent filmmaker, programmer, and cinephile-at-large based in Calgary, Alberta. He is currently the Programming Coordinator for Calgary Cinematheque. He is also producing his first feature film through the Telefilm Talent to Watch program.