In the title story of her 2014 collection of short stories God Loves Hair, Vivek Shraya writes: “I just want the chance to put on my mother’s velvet emerald-coloured dress. … I step into the dress and close my eyes. I let her Estée Lauder scent envelop me and feel her like a current of electricity, both warm and fierce. I become her. I am beautiful.”1This scene reverberates in her 2016 photographic series of diptychs titled Trisha.

Shraya, a trans woman of colour, has remarked that her body of work, which spans albums, books, films, and photo essays, is often informed by the oppressions she confronts as she moves through the world: racism, transphobia, misogyny, and biphobia among them. Shraya notes that Trisha emerged not out of a need or desire to delve into and make art out of trauma, but instead a longing to meditate on her mother’s femininity, how this femininity has been modelled for her, and how she can embody it herself.2

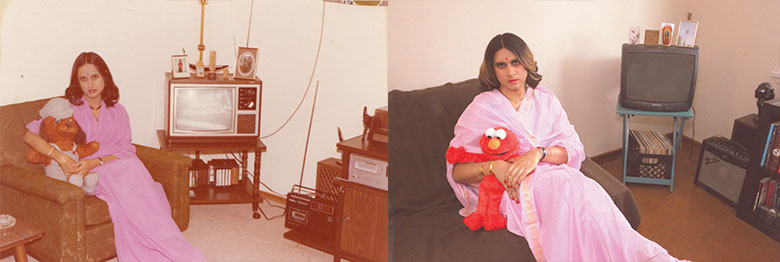

Trisha is comprised of nine diptychs, each one setting a vintage 6” x 9” photo of Shraya’s mother in conversation with a 24” x 36” photo recreation that sees the artist taking on her mother’s attire, expressions, posture, and gestures to honour the femininity that Shraya long admired in her. Shraya embodies her mother, recreating photographs taken of her before the artist’s birth.3

Shraya notes that Trisha emerged not out of a need or desire to delve into and make art out of trauma, but instead a longing to meditate on her mother’s femininity, how this femininity has been modelled for her, and how she can embody it herself.

The Trisha project was conceived of by Shraya and photographed by longtime collaborator Michelle Campos Castillo, a Salvadoran artist and illustrator based in Edmonton.4Though Trisha wasn’t born from the desire to challenge, unpack, or explicitly explore a particular social issue, Shraya nonetheless picks up on threads of past projects in a lively network of care that radiates, at least in part, from the subject of some of these projects: her own mother.5

Her admiration for her mother is particularly clear in the series’ second diptych, which captures Shraya’s mother in a green floral sari—one that evokes the emerald dress from the passage in God Loves Hair—looking at the camera from a brown couch. This is a pose which Shraya seemingly slips into effortlessly with her own green wrap and jewelry. It is striking to see the degree to which she has managed to inhabit her mother’s pose and expression. However, while Shraya aims to recreate the poses and outfits in the series, she does not seem to strive to replicate them exactly. This photo of her mother, seated and resting her hand on her stomach, is shot from a closer range than the recreated photo. Her expression is both seductive and defiant. Shraya’s recreation makes more space for her own body in the frame. This suggests to me that this is not simply a recreation, but a statement about the artist’s desire to embody fully a femininity modelled by her mother, and to do so with command.

Four of the photos from the series were shown recently at Christine Klassen Gallery in Calgary as part of a photography exhibition titled “The Female Lens.”6Co-curated by Heather Saitz and CKG, Trisha was exhibited alongside the work of eight other artists: Lori Andrews, Elyse Bouvier, Haley Eyre, Rocio Graham, Julya Hajnoczky, Dona Schwartz, Heather Saitz, and Diana Thorneycraft.7It is thanks to some exceptional curatorial work that the exhibition successfully rejected the idea of a single perspective of womanhood.8In the Trisha photographs we see the unifying thread of the entire exhibit: the interest in and insistence on subjectivity.

In the third diptych in the series, Shraya’s mother is draped in a pink robe, her arms wrapped around a stuffed animal. Shraya’s recreation alters slightly, and therefore personalizes, the photo. Instead of a dog, Shraya is holding on to a stuffed Elmo, and displayed atop the television, alongside a photo and a candle, is a Mariah Carey cassette. Shraya makes clear once again that this not simply a project of duplication, but a way for her to explore and render visible how her mother’s femininity has come to bear on her own representation of self. Like her mother, Shraya looks seriously at the camera. She is a woman influenced by her mother but whose subjective experiences have shaped her into someone also separate from her mother. There is a resemblance, but they are not identical. The photographs in Trisha investigate their respective femininities and subjectivities.

One of the pleasures of following Shraya’s multimodal art practice is how I can see her thoughts moving between projects, reshaped, and reframed across genre and form, to be seen, heard, and felt again from an entirely new angle. Her recent nonfiction bestseller I’m Afraid of Men, lauded as one of 2018’s must-read titles, had its start in a song on her Polaris Prize longlisted album Part-Time Woman. Themes and concerns from her film and book project on queer representation What I Love About Being Queer reverberate through her first novel She of the Mountains.

One of the pleasures of following Shraya’s multimodal art practice is how I can see her thoughts moving between projects, reshaped, and reframed across genre and form, to be seen, heard, and felt again from an entirely new angle.

The Trisha series also began in other projects. First evoked in God Loves Hair, photographs of her mother were spoken into being during the 2015 “Family Ties Tour” where Shraya toured her short film Holy Mother My Mother.9She says she would present a slideshow that included the photograph of her mother in the green sari: “Whenever I showed this picture of my mom in a green sari looking very sultry, I would make a comment about how interesting it was to see how much I now look like my mom. When you tour, you say the same things over and over again. By the fall, I was like, ‘Maybe I want to explore this more.’ It was touring Holy Mother My Mother and talking about the resemblance I was starting to see between my face and my mom that inspired pursuing it more deeply.”10

In a talk at the Annenberg Space for Photography in 2016, Alok Vaid-Menon, a gender non-conforming performance artist, writer, and educator, remarked that for trans and gender fluid and non-binary people merely being visible does not necessarily allow space for the acknowledgement of their subjectivity, and can instead perpetuate objectification and risk.11They argued that images of trans and gender non-conforming folks often circulate without the spectators of these images calling themselves to confront the reality of how trans and gender non-conforming people move through the world. Vaid-Menon stated that when people turn to art to assert themselves outside of white, cisgender narratives, subjectivity is at play; an exploration of what it means to shape one’s own story.12

Trisha is an interesting space in this regard, given that Shraya enacts and cultivates subjectivity in complex ways. There are two immediate and visible subjects of Trisha: Shraya’s mother and Shraya herself. Shraya is shaping her story in conversation with a story of her mother. To move through Shraya’s exploration of gender, identity, parental-child relationships, and ultimately of individual subjectivity, one must look not only to the photographs of Shraya, but also to those of her mother. The ways in which Shraya’s meditation on womanhood and identity in Trisha hinges on a conversation between mother and daughter reminds us how subjectivity can also be the result of recognizing and synthesizing the stories of those we carry with us.

By conceiving of the project, selecting which photographs of her mother to recreate, and writing an accompanying essay, Shraya plays both creative director and author of the project, narrating these found photos, and weaving her mother’s story with her own. She then renders this visible by stepping in front of the camera, casting herself as her mother, and creating a project that moves between her own experiences as a woman while exploring her mother’s experiences of love, joy, motherhood, and misogyny. “My story has always been bound to your prayer to have two boys,” Shraya writes in the accompanying essay. “Maybe it was because of the ways you felt weighed down as a young girl, or the ways you felt you weighed down your mother by being a girl. Maybe it was because of the ways being a wife changed you. Maybe it was all the above, and also just being a girl in a world that is intent on crushing women. So you prayed to a god you can’t remember for two sons and you got me. I was your first and I was soft.”13

In this essay Shraya acknowledges how her mother’s encounters with misogyny, and her negotiations with gender, are interlocked with her own and how these stories have come to bear on Shraya’s sense and presentation of her own femininity. Trisha is a space for Shraya to explicitly connect her mother’s story with her own, and render visible the ways each of their lives have been shaped by these forces. Shraya also writes about those stories that she doesn’t have access to, from a life that came before she did, that nonetheless impacted her: “I remember finding these photos of you three years ago and being astonished, even hurt, by your joyfulness, your playfulness. I wish I had known this side of you, before Canada, marriage and motherhood stripped it from you, and us.”14

This comment harkens back to her 2015 short film Holy Mother My Mother, a project shot in India during the 2013 Navaratri festival. According to Shraya, the film was meant to be about the festival and her mother’s relationship to it. Instead, Shraya shifted her direction to make space for her mother to offer her subjective experience of motherhood, one that was marked by both joy and sacrifice. In the film, Shraya’s mother says through tears, “Mother India reminds me of a cow that just goes on giving all the milk to all the children. She never drinks it herself. … There’s nothing left for her. She’s just giving and giving.”15Shraya recalls, “There’s so much in the film that’s not in the film. A lot of the heart in the film is the sound of her crying and what she is saying with her tears as opposed to what she is actually communicating. When she starts talking about Mother India and what Mother India has been through, I know she is talking about herself.”16

“I remember finding these photos of you three years ago and being astonished, even hurt, by your joyfulness, your playfulness. I wish I had known this side of you, before Canada, marriage and motherhood stripped it from you, and us.”

Holy Mother My Mother emphasizes Shraya’s ethics of care. Through her own words, her mother’s experience is represented in a way that attends to and honours the gaps in communication. Like Holy Mother My Mother, Trisha leaves space for her mother’s photographs to speak for themselves. She does not use the essay component to write over the photographs of her mother, or to offer an analysis of them. Instead, she gives them room to stand for themselves, and then stands herself beside them, as both a reflection and an evolution.

Trisha explores the indelible effect Shraya’s mother has had on her, creating a visual palimpsest that overlays Shraya’s life and experience over her mother’s. Shraya notes that the project was a transformative, cathartic exercise that allowed her to visualize and make sense of her mother’s, and her own, experiences of womanhood and misogyny. She said that after first looking at the Trisha photographs, she could see “only the differences between me and my mother, not the similarities, which contradicted the intention behind the project. But over time it’s become clear that this is a project about those differences as much as it is about the similarities between me and my mother. Those differences are essential to who I am, and reflect the ways that I have resisted some of the forms of misogyny that my mother experienced, and that I inherited.”17

Indeed, Trisha opens up this space of resistance for Shraya, serving as an opportunity for her to embody a femininity that was forbidden of her, to refuse a misogyny left to her by a white heteropatriarchy and by her mother’s prayers for sons and not daughters. These photos are spaces of refusal and resurgence. The artist adorns her body in her mother’s femininity, while simultaneously allowing her to embody her own. Both Holy Mother My Mother and Trisha inspire conversations about motherhood, childhood, womanhood, and what is lost or negotiated in the spaces between these identities. For me, several questions emerge from these projects including: what of your subjectivity is lost, is given up, when you are a woman moving through this world? What can be gained, held on to, protected, and used in the service of care?

Trisha gives visual space to how Shraya is beholden to her mother for demonstrating not only love and familial devotion, but a resilient femininity that she can draw from and mould into her own, in spite of the compulsory gender performance and misogyny levelled at her. In the Trisha essay, Shraya writes about how important her mother is to her: “I modelled myself—my gestures, my futures, how I love and rage—all after you. I was right to worship you. You worked full-time, went to school part-time, managed a home, raised two children who complained about frozen food and made fun of your accent, and cared for your family in India. Most days in my adult life, I can barely care for myself.”18She said that even Campos Castillo remarked that she felt that Trisha was the project that Shraya has been circling for years.19Care takes time and attention and Shraya has taken care with this project, circling it and only landing when she felt safe to touch down.

Shraya discusses how the photos she is recreating are mediated: “I suspect that many of the vintage photos of my mom are the ones that my dad took,” and then asks what it means to reframe the narrative in the way it is presented in Trisha.20Indeed, the first photo of the series is of Shraya’s mother standing, arms crossed and serious, looking up at a wedding photo of her and her husband. In the photo, presumably taken by her husband, there is a visible distance between her own individual, subjective self and the representation of herself as wife. In Shraya’s recreation she wears the same camel trench coat, her arms folded like her mother’s, staring up at the photo of her parents, the first two people who passed on expectations of gender to her. She looks at the same photo her mother did but from an entirely different subject position. What can be said in the space of a photo? What might the legacy of a photograph be?

Trisha is a project interested in the layers of mediation that exist in constructions of narrative, of photographs, and of identity. This diptych captures both Shraya and her mother as subjects who are also gazing. Perhaps this is what Shraya is contemplating—a history of representation mediated along gender lines, that positions her, as it does all of us, simultaneously as the inheritor and creator of her subjectivity—as she looks up to her parents’ wedding photo, now hung in a contemporary frame.

Trisha was exhibited at the Christine Klassen Gallery in Calgary from February 22 - March 16, 2019, as part of the group exhibition The Female Lens, co-curated by Heather Saitz and CKG. Programmed in conjunction with the Exposure Photography Festival.

Vivek Shraya is an artist whose body of work crosses the boundaries of music, literature, visual art, theatre, and film. Her best-selling new book, I’m Afraid of Men, was heralded by Vanity Fair as “cultural rocket fuel,” and her album with Queer Songbook Orchestra, Part‑Time Woman, was nominated for the Polaris Music Prize. She is one half of the music duo Too Attached and the founder of the publishing imprint VS. Books. A five-time Lambda Literary Award finalist, Vivek was a 2016 Pride Toronto Grand Marshal, was featured on The Globe and Mail’s Best Dressed list, and has received honours from The Writers’ Trust of Canada and The Publishing Triangle. She is a director on the board of the Tegan and Sara Foundation and an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Calgary. For more info, go to: vivekshraya.com