“We talked for hours and my hand slipped into hers. It felt so natural, so sweet, and tender...And we kissed. I thought, ‘Wow! You can kiss a girl!’She asked me to stay at her place for a few days. We slept in the same bed. I had never made love before. We woke up late the next morning. Our cheeks were flushed and our eyes sparkled.”1

Written, animated, and directed by Canadian Abenaki artist Diane Obomsawin, I Like Girls (2016) tells the stories of four queer women and their first loves: “For them, discovering that they're attracted to other women comes hand-in-hand with a deeper understanding of their personal identity and a joyful new self-awareness.”2Originally published as a graphic novel called J’aime les filles in 2014, the animated version is whimsical and heart-warming.

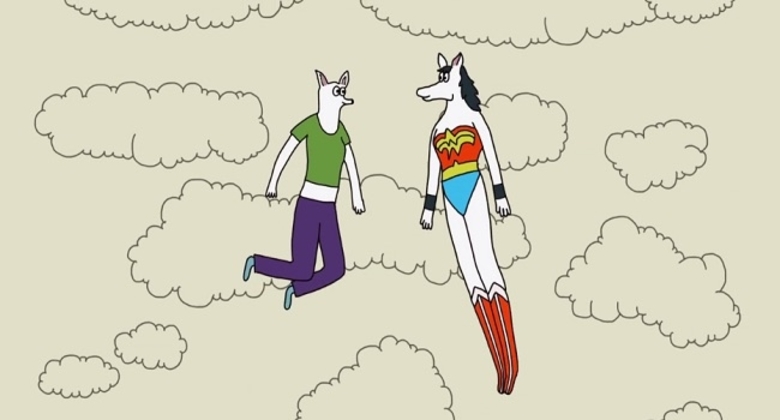

Using voice overs to narrate these lesbian experiences, Obomsawin draws the characters as a variety of humanoid dogs and horses. Mathilde recounts, “My first girlfriend was like half horse, half Wonder Woman. It was love at first sight. We were in heaven. We held hands and kissed where ever we went.”3Typical of Obomsawin’s animation, she imparts a sense of humour to tell biographical narratives, often about growing up, that focus on the small idiosyncratic moments and memories that make up a life.

In I Like Girls, when Marie goes to live with her girlfriend’s family, her mother shows up to take her away: “She sent me to live in a farm in Ontario to get me away from my girlfriend. I pinched the baby, I threw my [cigarette] buts on the floor. Anything to get out of there. But instead they gave me a cow to milk.”4We last see Marie sitting on a wood stool glumly milking a cow.

Diane, another woman in the film, says: “I liked girls but I didn’t know it. Until I had this dream about Greta Garbo. She leaned over and kissed me.I knew I was ready to meet a woman and it happened. I fell in love with Josephine.”5Obomsawin interprets this moment as two anthropomorphised dogs kissing in a stage wagon as they move through what looks like the deserts of Idaho.Her creative animation choices add a wonderful layer of quirkiness that makes you laugh or ponder more deeply what is being said.

Obomsawin discusses the film’s creation on the NFB blog. Inspired by hearing Quebec novelist Michel Tremblay’s realization that he was gay when he was sixteen, Obomsawin says, “Since I was curious and could recall similar stories from friends about their same-sex attractions, I called them and asked: ‘What’s the first memory you have of you being attracted to a woman?’In the end, ten of my closest friends told me their incredible stories that I adapted them into comics.”6When the graphic novel was adapted into an animated short, she says “we chose four [stories]: the most romantic, the funniest, the saddest, and the most autobiographical.”7

Estonian-born artist Chintis Lundgren, who now lives in Crotia, describes her work as having a “light, absurdist tone along with distinct anthropomorphic characters.”8Manivald (2017), is the story of a young male fox coming to terms with his gayness. An unemployed fox lives with, and is very reliant upon,his mother, sharing a simple life together. She does all the domestic chores, cooks for him, serves him coffee, and he plays the piano.

“You’re not going to feel like you are outed or shamed or misgendered. You can truly feel like you are with your community and you are being yourself and no one is there to make you feel unsafe.”

Their quiet life changes when Toomas, a rather buff and sexy wolf, comes over to fix the washing machine. The deep bass music that accompanies Toomas amplifies his sexy appeal in a humorous way. Manivald stares attentively as Toomas twirls his tools and leans over the washing machine, taking particular notice of his large fluffy tail. As there is no spoken dialogue in the film, Toomas returns Manivald’s desire by winking at him seductively.

Manivald’s mother appears equally enamoured by the wolf’s physique. She draws and sculpts him as Toomas poses provocatively for her. At first it seems that Toomas is only interested in Manivald. They get it on in his locked bedroom to a funny montage of horses running, the two holding hands and skipping across a field, and a champagne bottle popping.

Manivald has a new-found swagger and confidence until he discovers Toomas in his mother’s bed. This prompts him to move out and go looking for Toomas only to discover he has a wife/partner and kids. While I enjoyed this cute story of a fox finding independence and a greater sense of self, I found the character of Toomas implied some negative stereotypes about bisexuals. He is shown as being untrustworthy and is willing to sleep with anyone, even his new lover’s mother. Given that Toomas the kids at the door and the fact that he doesn’t invite Manivald into his house, the implication is that his queerness is hidden from his wife. In my opinion, this is some pretty tired biphobia representation that could have been avoided.

After the setback of finding his lover with his mother, Manivald embarks on a new life by joining a travelling band. Despite the potentially biphobic representation of Toomas, it was cheering to see Manivald find his joy as a piano playing troubadour with a group of other seeming outcasts.I hope his next dalliance ends on a far less bittersweet note!

In A Short Film about Tegan & Sara (2018), Asian-Canadian artist Ann Marie Fleming9draws stick figures on brightly coloured backgrounds to illustrate the career of Calgary born musicians and identical twins Tegan and Sara Quin. As the synopsis states, “Their remarkable journey over the past 20 years has often intersected with notions of identity—as artists, as individuals, as sisters, as queer women, and as leading activists in the LGBTQ community. Their musical progression parallels and amplifies their commitment to bringing the marginal to the mainstream.”10

My first impression of the stick figures was that they lend a sense of openness to the animation, that these two women could be anyone, thus potentially making their story more accessible to all viewers.I was pleased to see that this was also Fleming intention: “My animation is a very simple style. I feel like keeping it simple makes is more universal as well as making it possible for people to identify with the characters no matter where they find themselves or what they might be saying.”11

Tegan and Sara’s songs are used as a soundtrack to the twins’ voice over narration. Tegan says, “I’ve actually been thinking a lot about growing up in Calgary lately...It was a great place to grow up...I perceived [Calgary] to be quite open minded and alternative.”12They discuss their collaborations on creating music and their strong bond as sisters. Teagan states, “Whatever I create it is just better when Sara collaborates with me on it...I’m better with Sara” and Sara responds, “I’m with Tegan. I’ve got her back.”13

The animation draws attention (forgive the pun) to the duo’s Safer Spaces Program,which aims to make their shows a safe space for everyone: “You’re not going to feel like you are outed or shamed or misgendered. You can truly feel like you are with your community and you are being yourself and no one is there to make you feel unsafe.”14They have also established the Tegan and Sara Foundation to redistribute money from their tours to organizations for LGBTQ+ girls and women.15The “three pillars of our organization are health care, representation, and economic justice for self-identified women and girls in the LGBTQ+ community.”16

‘What’s the first memory you have of you being attracted to a woman?’

They talk about how the importance of openly discussing being queer. Tegan notes, “My visibility as a queer person has becoming increasingly important to me, especially as I get older and I find it important to talk about my identity with people. I love being gay.”17Sara responds, “I am so glad that I am queer and so happy that I am a woman...Being a twin, being a musician, these things have led to such a cool life.”18

The film was commissioned in celebration of Tegan and Sara winning the Governor General’s Award in 2018. Fleming says about the twins, “I think they’re incredibly authentic women. What the film is trying to do is make what is still marginally normal. To be able to expand the conversation to introduce their ideas of tolerance to an audience that maybe hasn’t heard them or doesn’t know them...I wanted to be able to do something simple and lovely to be able to expand their message. Their work ethic and commitment are amazing.”19

Canadian animator Shira Avni’s ten-minute animated film John and Michael(2004) celebrates the lives of two gay men with Down’s Syndrome. Typical of her work, the film addresses“questions of difference and social justice in ways that gently break down the viewer's habitual barriers [and] involves photography as well as clay-on-glass animation and painting, back-lit to create the shimmering effect of stained glass in motion.”20For clay painting animation,a type of stop motion animation, the artist paints each frame with clay by hand. The clay is moved around the surface like wet oil paints and then filmed frame by frame. In this film, the clay on glass animation’s combination of glowing light and dense dark areas is perfect for the subject matter.

We hear the story from a third person perspective about how the couple initially grew up together in a group home. One night they pushed their beds together during a thunderstorm and had their first kiss. They became boyfriends and lived together as partners. We see moments from their daily lives including John’s morning routine, the small things you notice when you live with someone. Sadly, their relationship ended John died of a heart attack at the age of 32. We see Michael leave his body as a bird in flight. Michael struggled after John’s death but is comforted by the memories of the times they had together: cuddling, dancing, giggling, and gazing at the stars.

Canadian documentarian and artist Lynne Fernie’s21seventeen-minute Apples and Oranges(2003)is the longest of the five films I have selected and was created with a children’s audience in mind. As noted in the synopsis, “this short documentary with interspersed animated vignettes is designed to raise children's awareness of the harmful effects of homophobia and gender-related bullying.”22

It begins with a live action scene of elementary school children who have been asked by their teacher to compile lists of the bad names that people say to each other. A number of the words they come up with are homophobic slurs including faggot, gaylord, gay boy, homosexual, tomboy, and dyke.

Students then come up to the front of the class, read their lists amongst a mass of giggles, and discuss strategies for dealing with bullying. They paint pictures of particular incidents of bullying. One student’s drawings hows a girl being bullied because her moms are lesbians. This drawing gets transformed into an animation by Fernie that expands upon the incident.

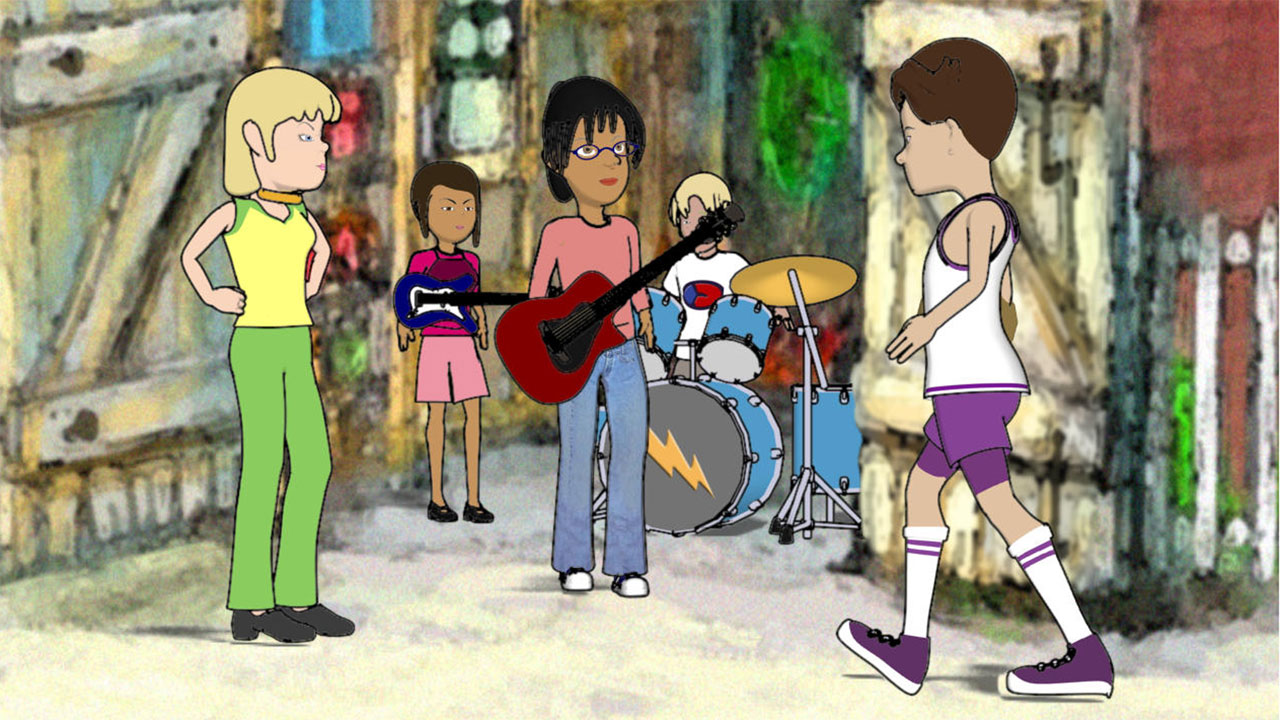

Cindy, a popular blond girl, makes fun of Anta for having two moms. In the next sequence, a talking cat tells Anta to get even and she decides to “make Cindy pay” and laughs maniacally.23She tries a couple of spells that backfire and result in Cindy teasing her even more. Her last attempt at revenge leads her to being suspended from school. With the help of her moms, Anta realizes she isn’t taking the right approach to the situation. She decides to write and perform a song about how “it is not cool to be cruel”24at the school’s battle of the bands. We see Anta’s moms in the audience cheering her on and the song wins the competition.

The film switches back to the classroom and a discussion about the student’s perceptions of gays and lesbians. One student points out that “It is okay for a girl to be a tomboy but it’s not okay for a guy to be a tomgirl.”25Another student draws a story about a boy called Habib who gets upset when his friend comes out as gay. In this animated section, his friend responds by calls Habib a homophobe. Another friend comes along and explains the term to him and says, “Just because someone is gay, doesn’t mean they have to be gay with you.”26Habib sees the errors of his ways, apologizes to his friend, and they resume their friendship.

The film ends with the teacher asking the class to compile positive words for, and attitudes about, gays and lesbians such as happy, respect, and treat them as you want to be treated. The students gleefully rip up their lists of bad words. Apples and Oranges does a great job of raising awareness by bringing issues of homophobia and bullying to a younger audience. Focusing on specific instances and how they were resolved is a particularly useful approach for this type of educational animation.

One of the main tenets of the NFB’s animation division is auteur animation which focuses on creating the artist’s vision. As former NFB chairperson Tom Perlmutter stated, “The kind of auteur animation that the NFB does is almost impossible to do in the private sector, because there is no financing or business model for such high-end creative work.”27Head of the English animation division Michael Fukushima says of the NFB’s approach to animation, “We have a legacy of filmmaking that we very consciously respect, and so there is a kind of filmmaker, for sure. We’re looking for auteurs; we are generally art-driven as opposed to content-driven, so poets rather than novelists, short-story writers versus journalists. Those are my short hands.” This auteur (rather than market based) attitude allows the NFB to champion animation projects that would be difficult to make elsewhere including all five of the films about queer identities that I have discussed here.

Stayed tuned for the second installment about NFB animation with a focus on feminist animated films in Luma Quarterly’s November issue.

If you are interested in creating an animation project, check out the NFB’s Hothouse apprenticeship program: https://www.nfb.ca/playlist/hothouse/