The venerable tabletop roleplaying game (RPG) Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) has enjoyed plenty of favourable publicity as of late, thanks to Stranger Things (2016-ongoing) and celebrity fans like Vin Diesel and Joe Manganiello. But this was not always the case. D&D’s early years were steeped in controversy, misinformation, and hysteria, tracing back to the 1979 disappearance of James Dallas Egbert III, a student at Michigan State University. His family hired a private investigator to try to find him, who learned that he participated in D&D sessions in the steam tunnels under the university. D&D was relatively new at this point; its first official products, created by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, were released in 1974. Egbert had attempted suicide in those tunnels, alone and unrelated to the game, but survived. He fled to Louisiana before eventually being found, and committed suicide by gunshot a year later.

The tragic Egbert case left a long and twisted trail, and this article will discuss some some strange filmic offshoots of that hysteria: the obscure Canadian film Skullduggery (1983) and the better known made-for-TV movie Mazes and Monsters (1982). Oddly, these two films have a cast member in common: Canadian actress Wendy Crewson.

Though D&D was actually a pastime for Egbert and played no role in his mental illness, wild speculations spread. Novelist Rona Jaffe's Mazes and Monsters (1981) inspired by the Egbert case. In 1982, the suicide of another young gamer, Irving Pulling of Virginia, prompted similar speculations. His mother unsuccessfully sued TSR 1, D&D’s publisher, and founded the advocacy group Bothered About Dungeons & Dragons (BADD). In 1985 BADD petitioned the Federal Trade Commission to require warning labels on roleplaying games, citing nine allegedly RPG-inspired suicides (though this was comparable or lower than the rate of suicides in general).

Other criticisms had a more religious character, accusing D&D and similar games of not simply warping vulnerable young minds, but of actually promoting Satanism, human sacrifice, and all manner of demonic practices. with some accusing the game of being “nothing less than an occult tool that opens up young people to influence or possession by demons.”2 Perhaps most famously, in 1984, Jack Chick released Dark Dungeons, one of his infamous religious comic series Chick Tracks, a hilariously overwrought and sensationalistic story of two young college students drawn into demon-worship through D&D.3

In 1985, 60 Minutes ran an anti-D&D story.4 Joseph Laycock, a Religious Studies professor at Texas State University, has authored a book-length study of this phenomenon. Laycock notes:

Conservative evangelical critics . . . effectively rewrote Egbert’s suicide, adding a connection to Satanism where none existed . . . In the 1980s, moral entrepreneurs continued to frame their attack on role-playing games in both religious terms as a “cult” and in medical terms as a form of brainwashing. But a new claim came to dominate discourse about fantasy role-playing games: that these games were actually designed to promote criminal behaviour and suicide because they had been created by an invisible network of criminal Satanists.5

D&D was not the sole target of such allegations; it was one front of the much larger “Satanic Panic” of the period.6 A similar target was heavy metal music and allegations of Satanic subliminal messaging via backmasking7, a topic that even reached the U.S. Congress in 1985. Possibly the most devastating phenomenon were the allegations of Satanic ritual abuse (SRA), where families were torn about by false memories and wild allegations. For example, the CBC podcast Uncover exposes how the Satanic Panic even spread to Martensville, Saskatchewan.8

By the later ‘80s, anti-D&D hysteria had died down, but TSR itself was cautious enough that the words “devil” and “demon” were all but banned in new products, replaced by the coinages “baatezu” and “tanar’ri.” The same cautious attitude prevailed behind the scenes. Game designer and author James Lowder describes placing a copy of the Chick Tract on his office door only to be sharply warned to remove it and fielding many phone calls from concerned citizens.9 The hysteria was on the whole not bad for D&D on the level of sales as it provided reams of free publicity. In 1984, a low-budget film initially called Ragewar changed its name to The Dungeonmaster, a name suggestive of D&D.10 Newspaper ads had to note that the film was not endorsed by or associated with TSR. Clearly there was some monetary value in hitching a ride on the controversy.

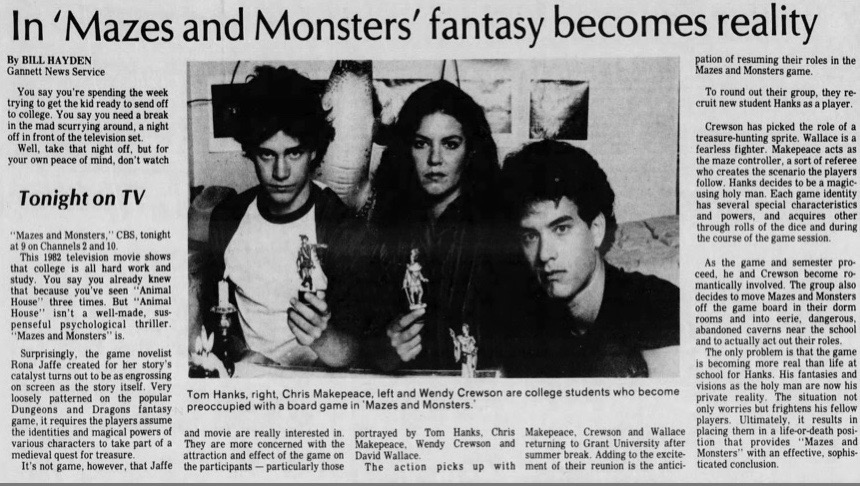

The Mazes and Monsters novel was adapted for CBS in 1982, shot in Toronto, and stars a young Tom Hanks, then known as the star of the TV sitcom Bosom Buddies (1980-1982). Hanks plays the Egbert-analogue Robbie Wheeling, a young college student whose mental health problems manifest as a delusional level of overinvestment in the game. He is drawn back into it by well-meaning fellow students, who decide to leave the tabletop behind and stage their campaigns in a local system of caves. Robbie starts to lose his identity within his character, the holy man Pardieu. He eventually flees to New York City, where he mistakes subway trains for dragons and stabs a mugger thinking him a fantasy monster. He plans to fly from the observation deck of the World Trade Centre. This suicide is prevented by his friends, who are able to find him and manage his delusions using their knowledge of the game. In the closing scene, Robbie’s friends visit him at his parents’ house but find him still in trapped in his Pardieu persona.

Today it is striking how non-hysterical Mazes and Monsters is. Its TV movie glossiness makes it appear neutered and anodyne. Its score is especially saccharine. The other gamers are depicted as occasionally eccentric but generally well-adjusted, friendly and loyal, and Robbie clearly has mental problems peripheral to gaming. Robbie’s friends manage to save him because of their knowledge of the game, while the police ignore their advice. It is also noteworthy that Robbie’s delusion leads him not into the demonic but its opposite: he fancies himself a figure of holy purity and breaks up with his girlfriend in order to pursue a vow of chastity. He imagines the world around him, especially the grimy early ‘80s NYC, as a sinful landscape populated by demons.

Robbie’s delusions ironically resemble those of D&D’s critics. Mazes and Monsters was never fully forgotten but received a cultural revival due to Hanks’ stardom and its rediscovery by prominent Internet reviewers. The game reviewer Noah Antwiler (AKA Spoony) reviewed it in 2010, granting it an exposure to a new generation for whom it played as a hilariously over-sincere curio from a vanished age.11

"Masquerade, theatricality, artificiality, performance, the blurring of reality and fantasy: all topics relevant to the anti-D&D hysteria."

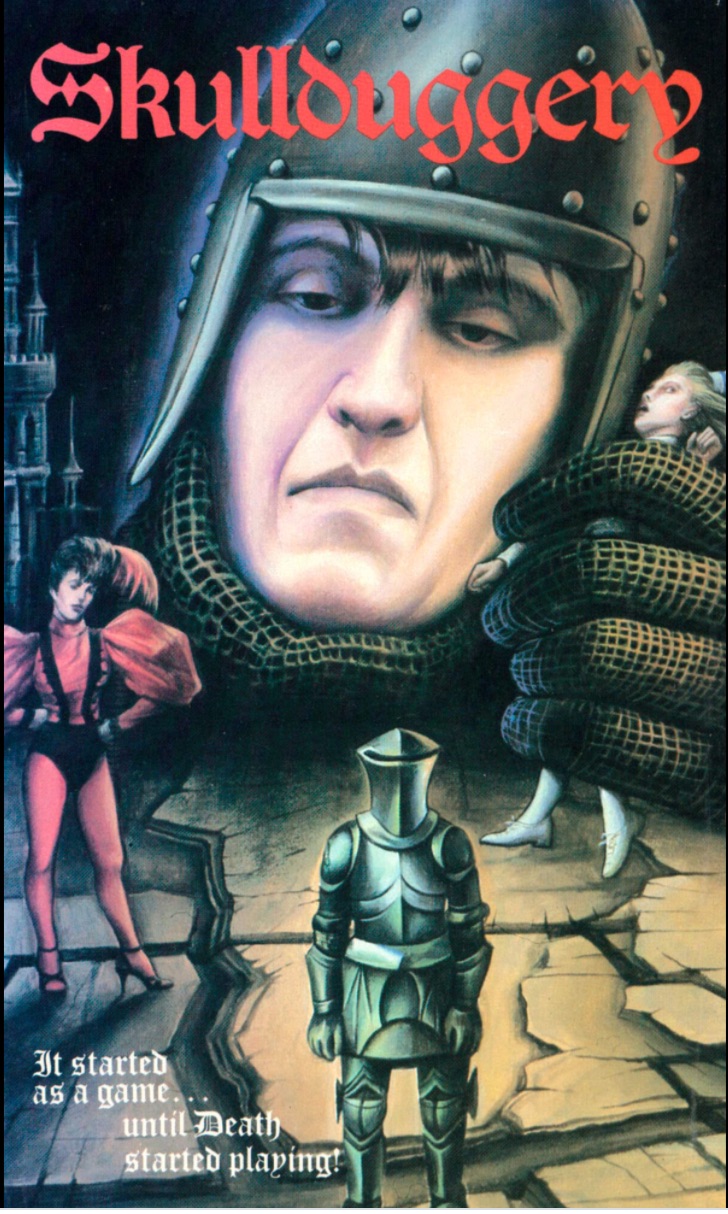

Far, far less known is the Canadian film Skullduggery, one of only two films directed by Ota Richter. It was allegedly shot in 1979 and went unreleased for four years.12 If this was the case, it was significantly ahead of the curve in exploiting the anti-D&D hysteria. Its French title was even Jeux de Rôles (role playing game). Where Mazes and Monsters was a hand-wringing social issue drama, Skullduggery is a horror film, at least to the extent that it slots neatly into any genre. By almost any measure it is a bizarre film that takes on a hallucinatory affect for being highly disjointed and tonally inconsistent.

Frequently kitschy but rarely comedic, Skullduggery might be classified, extremely charitably, as an art film/horror film hybrid.13 It has many inexplicable moments. For example, a nurse is introduced having a sexual tryst behind a scrim, only for it to be revealed that her lover is a doctor wearing a gorilla costume for reasons that are never explained. Later, fleeing for her life into a cemetery, she looks into a mausoleum only to see a Liberace lookalike playing a piano. She runs away, apparently as horrified by the pianist as by the murderer. On another occasion, the police chief is introduced with an assistant named Watson; the chief even says, “Elementary, my dear Watson” without a trace of irony.

Skullduggery has elements of a slasher film and of a demonic possession film but regularly swerves into other genres with little warning. It even becomes a teen comedy for a few minutes. A key early set piece is an amateur stage competition, which perhaps provides some explanation for its episodic quality and its stilted performances and stagy direction. The opening putatively takes place in medieval Canterbury but looks exactly like a cash-strapped stage production’s version of medieval England. Its figure of evil, a jester doll, is repeatedly seen bathed in a red spotlight. Presumably it’s meant to be simply glowing yet it casts visible shadows. There is also the recurring figure of sinister magician who performs his tricks directly to the camera. Insofar as anything holds Skullduggery together, it is masquerade, theatricality, artificiality, performance, the blurring of reality and fantasy: all topics relevant to the anti-D&D hysteria.

The film centres on yet another troubled young man, Adam (Thom Haverstock). The difference from Mazes and Monsters is that he is legitimately being manipulated by supernatural forces. He is introduced talking to his fellow gamer, a nurse named Barb (Crewson), about how their RPG experiences have been bleeding into reality. She describes hallucinating a dagger in place of a scalpel during an operation, and Adam agrees that “It’s hard to say where the game begins or life ends. Sometimes I feel like one of those figurines on the board.”14

Adam, who works at a costume shop owned by Barb’s father, is the inheritor of a curse placed on one of his ancestors by the Devil himself, sometimes referred to as “Dr. Evel” (David Calderisi). Adam starts to identify himself with the warlock character from his D&D-ish game and goes on a murder spree. First, he induces a heart attack in a woman playing Eve on stage by hallucinating a snake constricting her. He also stabs a fortune teller over an uncharitable tarot reading. Then the killing really starts, and he racks up a body count that would shame the most prolific of slasher villains.

Some of his crimes are directed by the Dungeon Master-equivalent, Chuck (David Main). He instructs Adam to kill a powerful young sorceress so he murders a nurse and presents a scrap of her clothing to the group as evidence of his success. The nurse had at first tried to seduce him with a cringe-inducing incest-themed roleplay. Much of Skullduggery has a similarly misogynistic feel. At one point, Adam comes upon two men attempting to rape a woman at a party, but rather than coming to her rescue he spears all three of them to death on a single long pike. Repression and internalized loathing of sexuality is a quality Adam shares with Robbie in Mazes and Monsters, but this time it is not explicitly a characteristic of his warlock character.

"Moral panics become available to laughter as they vanish in the rear-view mirror, but they are replaced by others, equally ridiculous and equally devastating."

Skullduggery’s third act more fully resembles a slasher film15, similar to Terror Train (1980). Adam murders his way through a costume party while repeatedly changing his own attire, at one point even dressing as a giant bunny. However, Skullduggery does not really provide the “final girl” element of the slasher formula16, since Barb survives but plays no role in Adam’s defeat. The film instead climaxes with a protracted gun battle with police in the costume shop’s storeroom It ends with Adam’s apparent death, upon which his body is replaced by the puppet.

The film’s final scene returns to the gaming table. They have brought Adam’s knight costume to the table and Chuck says, “We shall give Adam one final honour. He will share this game with us one last time.”17 They roll some dice using its gauntlet, and they come up six-six-six. One of the players says, “Here’s still with us. He is present, I can feel it.”18 Chuck reaches across the table but the gauntlet comes to life and drives a dagger into the chest. The costume collapses to the floor and Chuck falls backwards, taking the tablecloth and the gaming materials with him. When they peel the cloth off of him, it’s revealed that the now-dead Chuck is actually Dr. Evel. Is Adam finally getting revenge on the Devil for cursing his ancestor so long ago? If so, the weight of the moment is obfuscated by the fact that Dr. Evel’s corpse points a middle finger at the camera, like a metafictional “fuck you” to the audience for daring to expect any coherence. The final credits are scored with an upbeat, Polka-flavoured ditty.

On one level, Skullduggery resembles the most bizarre claims of D&D’s critics, since its Dungeon Master-equivalent is a Satanic figure who issues commands to kill that Adam carries out in real life rather than in the game. But in the film’s overall incoherency, gaming is just one Satanic motif among many. As the website Canuxploitation! aptly notes, “Dr Evel controls Adam through a variety of ways, including stage magic, and Adam's inability to distinguish between fantasy and reality really stems from an ancient curse. So blame the game for ruining teens if you want to, but you'll also have to turn off that Doug Henning special.”19 Skullduggery seems to exist to answer the question: “Can a film that is wildly overstuffed and bizarrely incoherent also be crushingly dull?” The answer is yes.

There is a temptation to talk about the anti-D&D hysteria and related witch hunts with a tune of bemused sarcasm. D&D survived all this hysteria and bad press, and now these campaigns against it feel quaint. Moral panics become available to laughter as they vanish in the rear-view mirror, but they are replaced by others, equally ridiculous and equally devastating.