The process of investigating a film’s production and pre-production is sometimes a sad one, for that feeling of what might have been. So it is with Alien Thunder (1974, also released as Dan Candy’s Law), which could, even should, have become an acknowledged classic of Canadian cinema. The talent was certainly there—screenplay by the legendary prairie writer W.O. Mitchell, a cast including Donald Sutherland, Chief Dan George, Gordon Tootsoosis and Jean Duceppe—and it was impressively resourced, apparently the most expensive domestic Canadian production to date. But Alien Thunder was beset by production problems, did poorly, and largely vanished from memory.

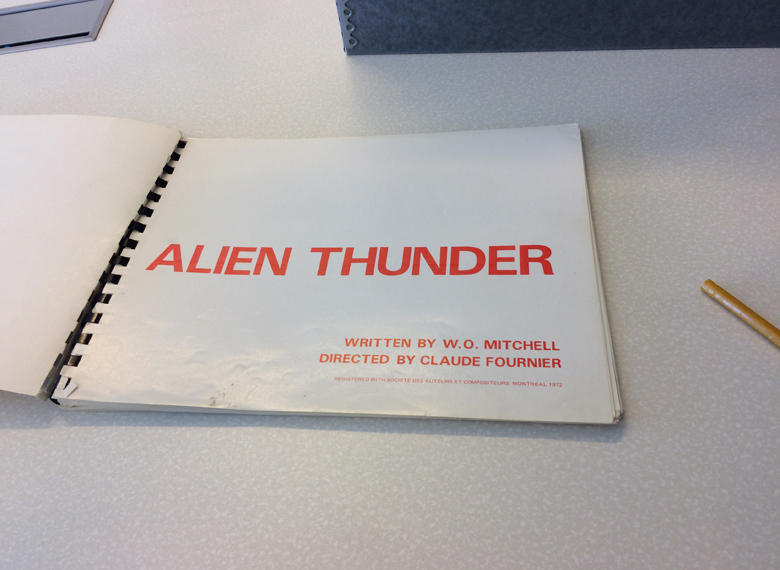

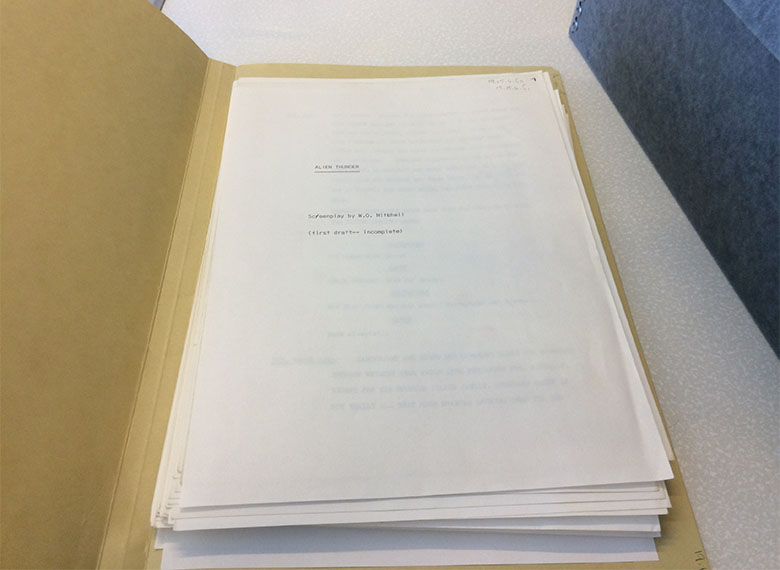

The W.O. Mitchell Archives at the University of Calgary hosts numerous drafts of the screenplay, extensive correspondence between Mitchell and director Claude Fournier, and even has a glossy, coil-bound treatment designed to persuade potential investors. Mitchell’s files, and especially his correspondences with Fournier, brim with an infectious enthusiasm for the project. In developing the script, Mitchell collected dozens of articles about the history of the NWMP/RCMP, and carefully researched myriad contextualizing subjects ranging from guns and chewing tobacco to Mountie uniforms and Cree marriage ceremonies. But Mitchell removed his name from the finished film, stating that “the script was drastically changed and my work was all thrown out. I didn’t even recognize it.”1Only occasional passages of his dialogue remained.2More of an interesting curio than a lost masterpiece, Alien Thunder nevertheless deserves attention for a variety of reasons, not the least for the fascinating true story it tells.

The film is based on real events in the 1890s, when Kitchi-manito-waya (Almighty Voice), a 20-year old Cree man, was arrested for slaughtering a government cow or steer and confined at Duck Lake, Saskatchewan. Almighty Voice was the son of Western Saulteaux Sinnookeesick (John Sounding Sky) and Natchookoneck (Spotted Calf, Calf of Many Colours), daughter of Willow Cree chief Kapeyakwaskonam (One Arrow). Born around 1875, just before One Arrow signed on to Treaty 6 and created the One Arrow First Nation reserves, Almighty Voice was part of the first generation to grow up in the reserve system.

Alien Thunder is not a story of square-jawed derring-do on the part of heroic Mounties. Instead it brims with Vietnam-era (and perhaps more relevantly, post-FLQ crisis) cynicism and anti-authority sentiment.

In 1885, One Arrow, Sounding Sky, and others from their band supported the North-West Resistance led by Louis Riel and Gabriel Dumont. Hundreds died in this violent five-month battle that was eventually won—using the Canadian Pacific Railway to transport reserves—by federal Canadian troops in the Battle of Batoche. Following Batoche, dozens of Métis and First Nations leaders were tried on various charges in an effort to squash additional anti-government sentiment. Louis Riel, six Cree, and two Assiniboine warriors were executed, and the legal marginalization of the Métis and Plains tribes in the West continued.

In October 1895, a decade later, Almighty Voice was arrested. In some accounts, the cow he slaughtered was the property of nearby settlers, in others it was government property; by Almighty Voice’s account, it was his father’s. He was arrested by Sgt. C.C. Colebrook and taken to the NWMP detachment at Duck Lake. In most tellings, guards joked that Almighty Voice would be hanged the next morning for his crimes; taking the claim literally, he escaped the next day, probably simply walking out when a guard fell asleep.3Almighty Voice swam over the icy South Saskatchewan River, collected his wife, Small Face, at the One Arrow First Nation reserve and continued travelling. After tracking Almighty Voice and Small Face for the next few days, Sgt. Colebrook was fatally shot by Almighty Voice when he and his Métis scout confronted him.

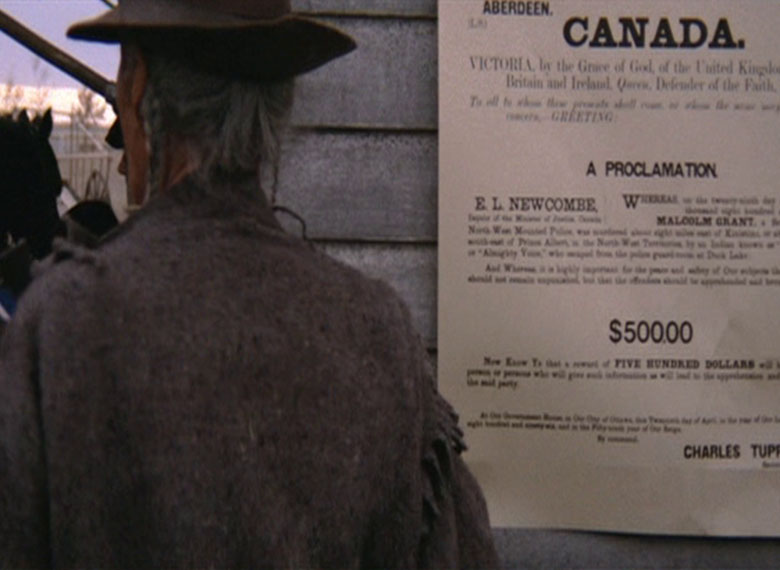

Almighty Voice was a fugitive for 19 months; though rumours circulated that he fled the area, he was actually hiding nearby, sheltered by the Cree. During this time, the NWMP started to fear that he was becoming another symbol of resistance among the local Indigenous population. Despite a $500.00 reward, he was never turned in by members of his band. Finally, in May 1897, word reached the NWMP of his whereabouts. They soon cornered Almighty Voice, his brother and one other Cree man, in a poplar bluff in the Minichinas Hills.

The three Cree men were surrounded both by the NWMP and deputized settlers. Gunfire was exchanged and Almighty Voice and his companions held their ground, fatally shooting two NWMP officers and the postmaster from Duck Lake, who had been recruited to help in the skirmish. A request for reinforcements reached the Commissioner at a police ball celebrating Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. Concerned that Almighty Voice’s status as a folk hero would inspire an uprising like the North-West Resistance, the NWMP chose a spectacular show of force, allowing for civilian volunteers to be made special constables and bringing in a 9 pounder gun and 7 pound cannon.4 NWMP and civilian volunteers numbering about 100 bombarded the poplar bluff intermittently throughout the rest of the day, killing Almighty Voice and his companions in the process. By the end of the affair, three Mounties and one civilian had died, three were wounded, and the three Cree men were killed.

Though the Canadian prairies have provided the landscapes for a great many American Westerns, domestic Canadian Westerns are a rare breed indeed.5Alien Thunder is a far cry from the lengthy tradition of (largely American) films about the NWMP/RCMP that died off by the 1960s, with late entries including Saskatchewan (1954, also O’Rourke of the Canadian Mounted). Alien Thunder is not a story of square-jawed derring-do on the part of heroic Mounties. Instead it brims with Vietnam-era (and perhaps more relevantly, post-FLQ crisis) cynicism and anti-authority sentiment. Building a fictionalized narrative around the historical story of Almighty Voice, Alien Thunder focuses on a composite character named Dan Candy (Sutherland). One of the first generation of settler children raised on the prairies, Candy is a loquacious NWMP sergeant. He helps apprehend Almighty Voice and later makes the joke that triggers his escape from prison. After the death of his partner, Sgt. Grant6(Kevin McCarthy), Candy craves revenge against Almighty Voice and runs afoul of his superior officer, Inspector Brisebois (Duceppe),7in his single-minded pursuit. August Schellenberg was originally listed as playing Almighty Voice but the role ultimately proved the acting debut of another great, Gordon Tootoosis; the father, Sounding Sky, is played by Coast Salish actor Chief Dan George with the same gravitas he brought to Little Big Man (1970) and The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976). Much of the film is consumed by a cat and mouse game as Candy tracks Almighty Voice across the prairies but finds himself lured into traps. Despite his desire for revenge, Candy is appalled by both the bounty taken out against Almighty Voice and the excessive force the NWMP eventually unleash against him and his companions. He tries unsuccessfully to persuade them to surrender as the massacre begins to unfold. The final standoff is one of the film’s most effective sequences, successfully conjuring up both tragedy and carnivalesque bizarreness, as the townsfolk put on their Sunday best and march through the prairie to watch the slaughter.

Filmed largely in Duck Lake and Batoche, Saskatchewan, near where the historical events unfolded, Alien Thunder was a troubled production. Interviewed for Cinema Canada in 1976, Fournier described inconstant investors and a production budget ballooning from $1, 100, 000 to over $1,600,000 due to legal fees; he also pointed to Sutherland’s contractual script approval as a source of frustration.8Consequently, the film feels simultaneously well budgeted (large, intricate sets, including a full-scale recreation of a prairie town, many extras) and threadbare, almost incomplete.

Mitchell’s screenplay provided a sweeping portrait of prairie life in the 1890s, featuring a large, diverse cast of characters (early drafts included Doukhobors and Chinese migrant labourers), an early-narrative trip across the Montana border to chase fugitives, and plenty of details about the cultural lives of colonial, Métis, and Cree communities and their entanglement. But because subplots from Mitchell’s screenplay never got off the page, characters like the widowed Emilie Grant (Francine Racette, whom Sutherland later married in real life) are introduced as significant only to become inconsequential later on. The Indigenous characters especially suffer; Métis scout Napoleon Royal (artist Sarain Stump) is a compelling presence but has a small fraction of his intended role, and a reduced part leaves Small Face (Ernestine Gamble) as just the kind of largely silent and passive Native American female so sadly common in Westerns. And without the planned denouement where Candy quits the NWMP over the mishandling of Almighty Voice’s case, even its protagonist’s character arc feels truncated.

As sympathetic as [Alien Thunder] may be to the Cree, they are, as the native peoples of the Americas tend to be in Westerns, reduced to supporting players in their own story.

The single most baffling omission is a scripted scene where Sounding Sky explains the origin of his son’s name. He says that he heard thunder when Almighty Voice was born, but also had a premonition that he would also die to the sound of thunder. This prophecy is fulfilled by the sound of the cannon—not the thunder that belongs to this land, but alien thunder. In context of Mitchell’s screenplay, Alien Thunder is a poetic title; shorn of explanation in the finished film, it is simply inexplicable.

Traces of Mitchell and Fournier’s attention to historical detail make it into the finished film, often in understated ways. When we see the poster declaring a $500.00 bounty against Almighty Voice, it is a modified version of the real proclamation, held in the Glenbow Museum’s archives. While the call for reinforcements reaching the Diamond Jubilee Ball did not get past the script, the image of a trainload of Mounties arriving in dress uniforms constructs a memorable surreal visualization of the police overreach. It is also pleasant that the 1.93 metre tall Donald Sutherland is noticeably too tall for the interior sets, which were obviously built to period-appropriate scale. But it is unfortunate that fears of Almighty Voice inspiring an uprising, as well as fresh memories of North-West Resistance, play little role in Alien Thunder, since the “unsettled” state of white habitation in the prairies is such an important context to the story.

Fournier’s talents as a director sometimes outweigh the film’s difficulties. The closing two-minute series of wordless tableaus of different onlookers’ reactions to Almighty Voice’s death, culminating with a moving composition of his family watching from a nearby hill, is especially sad and powerful. There may be no better film than Alien Thunder for conveying the “flavour” of pioneer life on the Canadian prairies in the late 19th century. It is not the only latter day retelling of the story of Almighty Voice; Rudy Wiebe’s short story “Where is the Voice Coming From?” (1974) and Daniel David Moses’s play Almighty Voice and His Wife (1992) are perhaps the best known. Though it laudably uses Indigenous (and principally Cree) actors and some of the Cree language, Alien Thunder is ultimately a film about Mounties and settlers; as sympathetic as it may be to the Cree, they are, as the native peoples of the Americas tend to be in Westerns, reduced to supporting players in their own story. Today, as the prairies are regularly reminded that colonial violence and systemic injustice are by no means things of the past, the story of Almighty Voice is ripe for revisiting on screen by an Indigenous filmmaker.

Thanks to Archives & Special Collections at the University of Calgary.