THE STUDIO: THE OFFICE

One houses a particularly nebulous type of labour, while the other is designed specifically to execute tasks. In the studio, where process is a goal unto itself, completion isn’t necessarily a precursor to success. In the office however, where labour is directly translated into tangible product and capital remuneration (not cultural capital, mind you—the real stuff that pays the rent and puts gas in your car), tasks are generally required to be complete, in the most concrete sense of the term. Speaking about the process for “Real failure needs no excuse,” currently on view at Calgary’s Esker Foundation, Marilou Lemmens reflects that “if you don’t have a goal when you act, there isn’t an end for an action. It can continue forever.”1

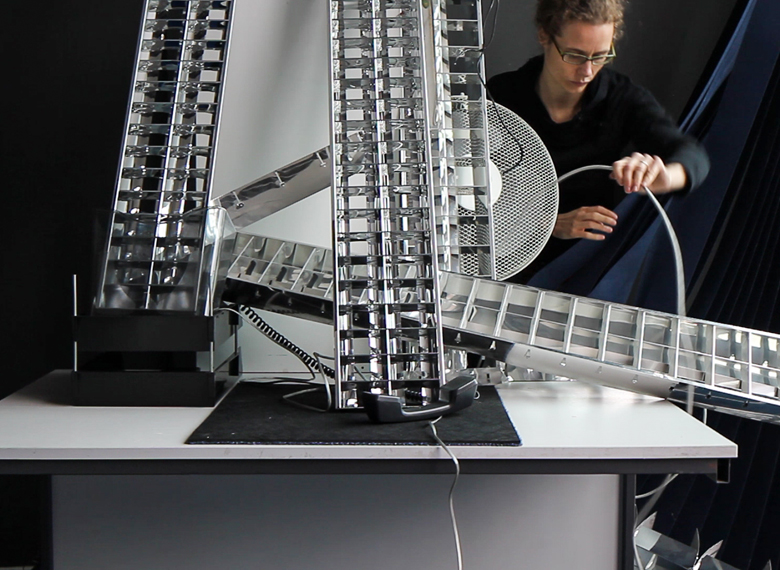

In this 2012 piece, Lemmens moves into an abandoned Glasgow office and adopts it as her studio, conflating the two breeds of working spaces. Sporting tennis shoes, jeans and an intent look of concentration, she balances and adjusts discarded office debris according to some unknowable logic, one that defies the conventional purpose of office supplies in favour of the experimental process of formal composition. She’s definitely working, but as the arrangements are modified and re-modified, it’s clear that this labour has neither a goal nor an end in sight.

PROFESSIONAL INSTABILITY: FUNNY IN CONTEXT

The work itself isn’t new, and neither are the artistic interests at play. Richard Ibghy & Marilou Lemmens have been focused on labour, (non)productivity, capitalism and related notions of workplaces, collaboration and goals in their studio practice for more than ten years.2

Yet, the exhibition of this work in Calgary is markedly timely, with Calgarian office occupancy rates sitting at a notable low—20% vacancy as of spring 2016.3 My favourite Calgarian radio ad this summer is staged as a casual conversation: one speaker has been unemployed for some time but is learning to see their situation in a positive light. Their extra time and severance package has allowed them to start the small business of their dreams! Like this ad, Ibghy & Lemmens’ work isn’t a joke, but it is a little bit funny. Richard Ibghy notes that there is a humourous quality to engaging with “fax machines, file cabinets, etc.”—materials and objects that are designed specifically for “maximizing productivity”—in a manner that essentially eradicates their original purpose.4

This broadcasted optimism voices an internal process that many un- or underemployed Calgarians are undergoing after watching their careers collapse alongside gas prices. Being forced to face the precarity of traditional professional success is putting us in a place, collectively, to reconsider how we determine the value of different types of productivity.

WORK WORK WORK WORK WORK5

Comparing creative labour and capital labour is a fun exercise because much of the vocabulary overlaps, even though the experience of people working in these two realms is so radically different—the motivation for why so many cultural workers get asked, “but what do you DO?”6

Work is a physical or mental activity undertaken to achieve a purpose or result; or, the same, but as a means of earning income; or, something done or made, ie. what an artist produces. Labour is also work, especially hard physical work; or, to make great effort in any context.

Canadian writer Sheila Heti published a book in 2010 titled How Should a Person Be? that functions as a blueprint for how young white artists go about surviving in late-capitalist Canada, which (as a member of that specific social sect) is in turns both comforting and horrifying—like an episode of Girls for cultural workers.7 Woven through the narrative is a disturbingly accurate description of the young artists’ lifestyle: the struggle to produce creative work on a deadline, juggling eccentric selections of part-time jobs, drinking at gallery openings, the erratic sleep schedule that accompanies all of this. Now, anyone can read this book and get an idea: this is a version of what artists do. What their work is, and what they do FOR work, and how that difference plays out in day-to-day life.8

A job is a paid position of regular employment. Capital is financial wealth in the form of money or other assets, eg. What you receive for working a job; or, a valuable resource of a particular kind—eg. Cultural capital: embodied, objectified or institutionalized social symbols that symbolize cultural competence and authority, or, what well-educated cultural workers earn in spades.9

CULTURAL CAPITAL IN THE “CULTURAL CAPITAL”

Back in 2012, Calgary was named the “Cultural Capital” of Canada, which came as a surprise to cultural workers trying to pay Calgary rent prices with their “cultural capital.” National titles aside, the general social climate has not historically been the most supportive of those choosing to work in arts and culture, especially while more lucrative career paths were so readily available.

Popular opinion claims Calgary has been experiencing an oil-and-gas related recession since 2015, and those career paths are now just as unreliable as the arts-and-culture route. Perhaps smart artists should start promoting themselves as self-employed entrepreneurs, as per the previously mentioned radio ad. A start-up spirit and innovative individualism are, after all, pillars of the Western Canadian settler value system. Aligning ourselves accordingly should get us through until the Calgary Economic Development’s plan to diversify our economy through the arts, specifically the Calgary Film Centre and the National Music Centre, gains traction, and careers in the arts gain local popular recognition.

A REAL JOB

A major reason that Ibghy and Lemmens have chosen to focus so intently on non-productivity in their studio practice is to disrupt the enormous external and internal pressure that cultural workers face to be hyper-productive…“not only during the time that they’re at work, but also outside of work, which raises a lot of questions about quality of life and being able to enjoy moments during which they are not being productive.”10 This mirrors output expectations experienced in other economic fields, both for creative research and output, and more problematically, for administrative labour and traditionally “productive” tasks (eg. grant writing, budgets, copy for statements or bios, web development), which, when performed independently of a job, end up going unseen and unpaid. Perhaps a video of an artist filing their paperwork is what Calgary really needs to see.

Have you heard the one about the arts administrator who left their long-time job running a local theatre company to work as a project manager for Encana? They cashed in their cultural capital for the real-deal variety, and now what? I don’t aim to critique that choice so much as express genuine curiosity. How is the exchange rate between the two fields in Calgary these days?

A VALUABLE JOB

Does getting paid for doing the thing we are critiquing have to cancel out the value of what we produce, or, why does monetary capital have to negate cultural capital? “Real failure needs no excuse” is primarily concerned with critiquing productivity, and so is not explicitly geared towards addressing this question, but it is one that is raised as we consider the hierarchies of labour implied in the piece. Preferring to highlight conceptual and formal merits of artistic work, while minimalizing other forms of labour that go into supporting it—whether that’s arts administration, the labour of technicians, or the labour done by artists in service or maintenance jobs in order to support themselves—only recreates the hierarchies of value that exist between cultural labour and corporate labour, or between service and business–oriented labour.

Performative artist Mierle Ukeles wrote in 1969 that “the culture confers lousy status on maintenance jobs = minimum wages, housewives = no pay.”11 As a mother, her work was produced from an experience of domestic maintenance, and is almost always read from a feminist perspective of invisibilised feminine labour, but as this quote indicates, her practice also touches on invisibilised labour performed in the public sphere, and those who typically perform it (working classes, recent immigrants— in short, those with less capital, financial or cultural). As part of the larger reconsideration of what constitutes “valuable” work in Calgary, this poses an opportunity for cultural workers to intentionally align our cultural capital with our sources of monetary capital, and those who share in that source of income. To marginalize that type of labour in our own lives is to marginalize those for whom this constitutes their entire working lives, which is not only unkind, but lousy cultural practice to say the least.

THE OFFICE: THE STUDIO

Additionally, maintenance and service work is often repetitive or meditative, and allows for deep observation of spaces or people, which can make for rich artistic fodder—not only for emerging artists, but also for artists who support themselves in this way long-term; perhaps for their entire careers. Observation of the office space is Lemmens’s main task in her performative exercise, employing her artists’ eye as she mines the environment for materials. The decontextualized and abstracted use of corporate tools is, at first, mostly comical, the formally engaging qualities of the materials and arrangements become more apparent as we exercise our own powers of observation over the length of the video.

Warm wood panels contrast nicely with a cobalt-blue carpet. Textiles exaggerate gestures when draped over the performer’s body. There are large scenes—entire rooms arranged and the process documented as we witness all the different ways cubicle walls can interact with one another. Doorstop; raw pine, whiteboard markers. Smaller compositions include a tabletop study of a printer balanced on leftover break-room marmite, a cable artfully arranged; Lemmens’s temporary arrangements make formally effective studies.

The cuts in the documentation video accelerate, erratically, to some comical apex that never comes, continuing on instead in a banal loop. Lemmens takes a lunch break; and why shouldn’t she? Despite and because of her excellent labour as an artist, the arrangements shift and collapse. And why not? Why should we expect anything other than collapse? And why not take a moment to laugh a little at the underlying instability of our every day practices, the ultimate failure of even our best professional efforts?

GOOD ONE, GUYS

In a time when Calgarians are feeling vulnerable around the definitions of their labour and employment, the Esker sets an example for effective mainstream cultural programming by holding space for critical reflection on the current cultural climate. The Esker has their eye trained on engaging and relevant Canadian artists, while still maintaining a grasp on their immediate surroundings—something that is encouraging.12 Perhaps we are entering a time where interested Calgarians can refer to their cultural institutions to inform them through such moments of vulnerability, as we reevaluate not only the hierarchies of fields of labour, but also our understanding of financial vulnerability, the importance of community and culture in our everyday lives, and how our work plays into all this.

I’m optimistic that our city’s institutions, large and small, are working to continue building our cultural identity, and toward intertwining Calgary’s reevaluations with current national and international conversations.We are hard workers, and I’m excited to see what permanent or ephemeral projects we can produce—so long as we take care of ourselves in the process.

Richard Ibghy & Marilou Lemmens' Real failure needs no excuse is showing at the Esker Foundation from May 28—August 28, 2016.