what is the point to analyze

life when life itself seems to be

such a careless and unpredictable

performance?June 13, 2016

↩

Cradled by my phone’s heartbeat, I spent hours on the couch, staring

at the different ways in which the world (or rather my uneven

experiences of it) reflects its textures inside the murky surface of this

wi-fi network that now, like a mental IV pump, infuses my

thoughts with bizarrely random and sometimes paranoid

streams of news coverage, Facebook posts and outbursts of personal

gestures that comment on, as they rearrange details from the recent

Orlando nightclub shooting in Florida. Next to this endless

precipitation of images, one thing is clear—that the more I think about

these events, the more unable to write I feel: I don’t know anymore if

what I am unable to write is a text that performs itself critically, and

vigorously critical of its criticality, or if something deeper from inside

me had snapped in such a way that criticality—or the labour that one is

prepared to invest in their attempt to, to, to change what they want to

see changed in the world; if the idea of an activist textual action, at this

present moment, has renrendered itself to be counterproductive to

reaching any sort of sensible resolution. (with this I wonder if it is

possible to change the world through one’s absence from it, and if so,

how can this inaction, act in the world ? aaand.. can passivity be

performed as a form of political action ? )- ↩

- ↩

- ↩

- ↩

- ↩

- ↩

Although I was five years old at the time, one of my earliest childhood memories is marked by

the crackling sound of bullets as they dug their way through the walls of the nearby apartment

buildings where I grew up, in Bucharest, during the 1989 Revolution. Today, having lived in

Canada for a large chunk of my adult life, looking back on these events with a somewhat detached

perspective, I see the 1989 Romanian revolution as part of a larger political moment that had began

to change the East-European reality with the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 10, 1989, and

which continues to unfold to today, as member nations of the former Eastern bloc struggle to

find links between their own regional identities and a larger, western, globalized context.

What makes this specific memory a pivotal event for me however, is how the experience of the

revolution, at the time, made me recognize the possibility that reality could become something

that is not always experienced in the same way by everyone, even if the circumstances that frame

our experiences of reality in a given moment, are the same.As I re-walk through the images from that day, I remember being gathered together with other

local children from the neighbourhood and then brought to, uh, to an upper floor apartment with

darkened windows where we were told to begin playing a series of imaginary games, the same

games, or rituals, that we usually played with each other when on the street, but now

within, ah, the enclosed perimeter of this strangely un-lived apartment; a gesture which

communicated, nonverbally, this concept that our play should figurate the shape of its

own outside-of-the-current-reality reality. And that is exactly what we, as kids, did,

nonverbally, but also very consciously and deliberately, perhaps to satisfy ourselves, but

also to satisfy the others; the others that were there with us, and the others that were on

the other side, downstairs, outside of the apartment, trying to permanently shift a larger

political reality. I don’t remember the exact games we played, but I remember feeling like

I was under the spell of this strange combination of feelings that at any moment could

have slipped from that almost artificial excitement that one surrounds themselves with in

order to fit-in when amongst an uninvited group of bodies, towards this abrupt physical

fear that something irreversibly “bad” can suddenly take place.Years after I first enacted these mental moves as a way to subvert my perception of reality,

↩

which, witch, witch, which as I learned later, were performing simultaneous temporalities

through which I could then proceed in parallel and invisibly towards places and worlds from

within these spaces that were themselves far away from the reality that referenced them, I find

myself continuing with seeking their views, but now as they make up working surfaces (here I

imagine a catalogue of rare, Bauhaus-style desks with stark, clean, modern lines that exist

invisibly and on-demand through the kind of-of-of imagination one gains access to, from

and because of writing) sssuuurfffaaaceeessss—surfaces from where to write and to think from,

surfaces that through their open architecture(s) give me, or the character that plays me in

the writing position from where I write them from, the, the, the choice to in a sense

“direct” how these influence what I write and how what I write performs in real-time, my

staging of someone—a character, a man—actually, many kinds of men and women and

other non-non-non-human things and objects, each with a different voice and a, a, a, a an

ann individual style of speaking and thinking; a self-multiplying double image if you'd

like, that stamps its desires on the world, and in the world, on my behalf as it follows, or

thinks with and-and-and-and-through the lives of other people // and then how in turn,

these images themselves, collapse into unmoored situations / thought precipitations,

themselves erected, erecting in the world: this world and their world simultaneously.

Performatively acting out of a textual version of reality without words and through other

characters or the satellite ideas of those characters that live life, or versions of their life

on, on—my behalf, is something that I seek and occupy with a great deal of pleasure

because, be-be-because once one is cornered in this way of living, like-suddenly-beingsucked-

inside-their-smart-phone-screen-and-then-directed-to-the-insiiide-of-a-paralellworld-

app there is no other option but to construct separate, more fulfilling lives that live the one

that you dddon't want to live any longer, on your behalf./ city of angles

something I wrote for myself the other day on a piece of paper that now rests

crumpled somewhere at the bottom of my backpack, like a textual totem that I’m

keeping to remind my future-self of why I need to write, and how I need what I

write to continue walking:You search for hours and hours—until you hear their voices.

First, you walk to the places where you saw them the day before,

and then if they're not there, you go to the places where

you imagine they might be.

Some places are out of the way

while others, if you have spent years to search for different angles

like you wanted to when you wrote this note,

have, by now, become familiar to you.Sometimes you've seen them sitting on a bench in a train station,

and sometimes they're lying down

underneath the, the, the same tree from the park

that you pass through each day.

And then, when you don't see them,

they're probably just flying above,

at a distance from where you and your problems

appear as only an insignificant dot

in a landscape filled with many other,

more important emergencies.When you do find them, they'll usually make you smile.

And then, with them, you start to write

because writing to you is never really a solitary act.But right now, as I'm writing this note to my future self, to you,

I, i, i, i—still think of them, the angles, as my reader

and I don't knowwww if I'm supposed to share

what I write for them with others.

So far, they’ve never said a thing

about who else should read my thoughts.

But then I don't know if the others are, actually real.

Or if the angles are not [real].

I just don't know. So I walk because I don't know.

And I don't know if I want to know that the angles are not real.My grandmother used to search for angels in her neighbourhood in Bucharest. Sometimes

she would take the bus and stop by at all the cemeteries and churches from along the way

(which, if you are in Bucharest, there are many... almost too many, perhaps as many as

the number of Starbucks coffee shops we might encounter in our walks in downtown

Calgary. Perhaps as a way to map out the material and spiritual experience of walking in her city,

she would collect small things that made their way into her life along this invisible

pilgrimage. Sometimes through these trips, she would meet others that were also in

search of angels, and then they would exchange information, the coordinates of specific

walking trails and other phenomenological sites and stories that they needed to be aware

of. Looking back, I always thought of this way of walking, which in a sense is a

performative interpretation of the city as a site for shared, unorganized spiritual

experience, as a kind of portal for making an exit from reality without actually

abandoning it—something that is close to a survival mode that perhaps is related to how

my grandmother's generation of women had to think about their day-to-day life, as they

searched for ways to subvert and soften the rigid regime that communism had imposed on

them throughout their lives. And this ritual of simultaneous withdrawal from, while also

being present in reality, is something that I have come to develop and then put to use

many times throughout my own life as I transitioned from one form of the then-extreme

East-European communism to it’s chaotic interpretation of democracy and capitalism and

then later, to the not-so-radically-different & institutionally disguised North American

infrastructures designed to recycle present-day versions of democracy and its utopian

ideologies into the self-destructive and never-ending expansions of the neoliberal

metanarrative that, and much like a different kind of subversive ritual, also seeks to direct

its own stylized stagings of reality—as if the condition of consciousness today was a

sculptural and malleable surface that is attached to, to, to interchangeable price-tags and

profit-driven values.

It is at thiss collapsing point, between what things once were and the

way their remains

(re)animate themselves through our

realization that history is itself a material

practice that embodies simultaneous temporalities

and spaces whose agency is coded directly and

invisibly in the lived present, where I

place my experience of “Portal”, a recent project

by Sandra Vida that showed this summer at Emmedia

in Calgary. Set in a black-box environment, and

from a formal perspective, Portal was an immersive

experience that is both an installation and a

performance, as it asked the viewer to use their

own imagination to move through, with, and inside a

roving bricolage of projected images and sound

samplings. Conceptually, the project directed

attention to the metaphoric potential one might

gain through movement as their own body

penetrated the projection screen to, to, to in a sense,

individually choreograph the image (or its

psychological state)—a collaborative, dance-like performance

that in a way transformed the viewer’s

role in, in, in the installation from that of being a passive witness to a

a hands-on collaborator. Complementing this

thought that a work of art is never really finished

as it continues to mutate through the individual

experience of each viewer, the video in turn,

presented organic abstractions of shapes and forms

that were reminiscent of self-spreading virus

formations and sites of infection, perhaps also to

reinforce the idea that art, within a culture of

domination (as Bell Hooks pointed in this

summer’s issue of Artforum “at this particular

point in time when our political struggles risk

commodification in ways that diffuse their radical

intent”// art cannot, itself, risk being appropriated (or

infected) by the things that undermine its radical potential to highlight what we usually

take for granted.

But, unlike other activism-inspired projects that

we so often see and experience today, either in person

or over the internet, what Portal offered differently, is a quieter and softer call to action; a

plea that doesn’t prescribe us with its

own, often-aesthetized-and-later-commodified set of

ethical guidelines for what we should do and then

how to do this, but it rather gently

reminded us that as individuals, despite living in

a globally-unconnected-but-connected-multicultural-and-multinational-

chaos still have the agency to

cause positive changes in the immediate visible or

invisible world(s) from around us, and perhaps this

is more effective and empowering when we perform our agencies as

individuals that can push themselves to have an

outside perspective on what’s going on from the

inside of our own lives. Thinking alone in ways that are optimistic, at a time when we’re

always together is perhaps the most radical thing we can do today… and yes, there is

definitely an unarguable strength in acting and working together towards a shared cause

(I'm thinking of Wafaa Bilal’s 168:01 project that showed recently this summer at the

Esker Foundation in Calgary, which proposed the reconstruction of the Bayt al-Hikma in

Baghdad, but I think that on

a different scale, small, almost-invisible and disorganized gestures that come from

individual impulses to better the world are as effective, and we should not forget that

there are also positive aspects to individual forms of agency, which at some point could,

in a sense, collapse and spread virally (going back to Vida's performative videoprojection)

to form a yet-to-be articulated starting-point for a new kind of shared

activism that happens unannounced and from within the inside of multiple struggles

rather than from an overarching political meta-narrative that is easily catalogued and

interpreted (to borrow from Susan Sontag’s famous essay “Against Interpretation”, 1966)

within an already established cannon that interprets what is, and how activism should be

organized.https://static1.squarespace.com/static/54889e73e4b0a2c1f9891289/t/

↩

564b6702e4b022509140783b/1447782146111/Sontag-Against+Interpretation.pdf- ↩

- ↩

* * *

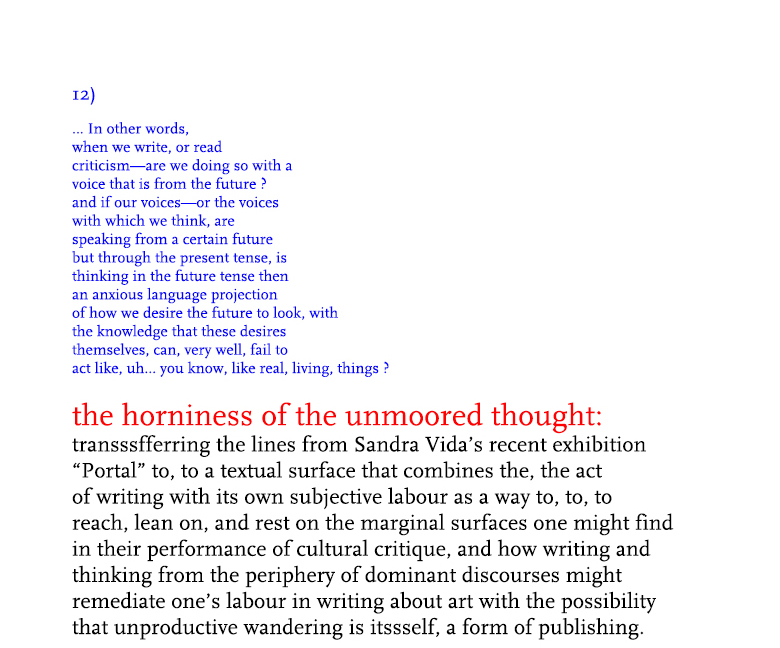

With transferring the lines from

Sandra Vida’s Portal to a “living"

text-based format that is more

interested in the experiential

and material side of the labour used in

writing about art than in the final

textual packaging of criticism,

I’m wondering if spending time to

think about a work of art without

trying to print it in concrete

terms, is, is in a sense, a way of writing

that on the one hand is unproductive within

a conventional publishing context, but then

productive as an artistic form where

the idea of criticism itself, is not just a "backdrop" for

other ideas,

but also a kind of aesthetic that

can be related to the everyday, and

then practiced daily, as a way of life.

↩

// http://astronomy.nmsu.edu/aklypin/AST506/Violent.pdf

Sign up to be notified when our next issue is released, or follow us on Twitter.