In the conventional dark box, a video projection predictably illuminates the rear wall. Viewers watch a withered leaf suspended by a scarcely legible spider’s web in an Amazonian rain forest. Comic and improbable as this image appears, one quickly projects onto this found puppet-like apparition the sentimental sympathies associated with the antics of Chaplin or Keaton. Like other viewers, I sat transfixed as the leaf repeatedly regains its equilibrium from the subtle buffeting of air currents. A large part of its fascination is the way in which the leaf oscillates between being a still and moving object of the camera’s, and our, gaze.

This is less an exhibition of photographs than an exploration of the scopic imperatives that underlay the history and practice of photography. While all representational art relies on mimesis, photography privileges observation at its essence; through composition, selection, the manipulation of scale, it stops and focuses the roving eye, working against cognitive tendencies to observe, identify, assess, and dismiss the overwhelming quantities of observed visual information. Photography once had the inherent possibility of arresting the viewer’s wandering attention, now largely lost by the dizzying ubiquity of photographic images. Colin Miner seems to take up the challenge of Behaviorists’ clocking of the few seconds museum visitors actually spend looking at most works of art, through a series of somewhat Brechtian distancing or alienating effects (Verfremdungseffekt) that startle the viewer into a more meditative response.

This effort to make strange is heralded in the entrance to the exhibition, where the corkboards along the narrow entrance corridor have been ‘curated’ by the artist, who carefully reorganized the random invitations to other gallery exhibitions, and arranged the extra pushpins in what appear to be astronomical constellations. If the Medusa-like freezing of the camera’s action is a recurring theme of the project, it is signalled by the exhibition title, His dreadful glance—a phrase from Sten Nadolny’s The Discovery of Slowness, a novelization of British Arctic explorer, Sir John Franklin, and a meditation on “slowness” of vision, thought, and speech.1 This phrase greets gallery visitors, almost invisibly, in white laser-cut vinyl lettering mounted on the white wall at the end of this entrance passage. Only after having consulted the exhibition checklist handout would most visitors return to ‘discover’ this occluded warning.

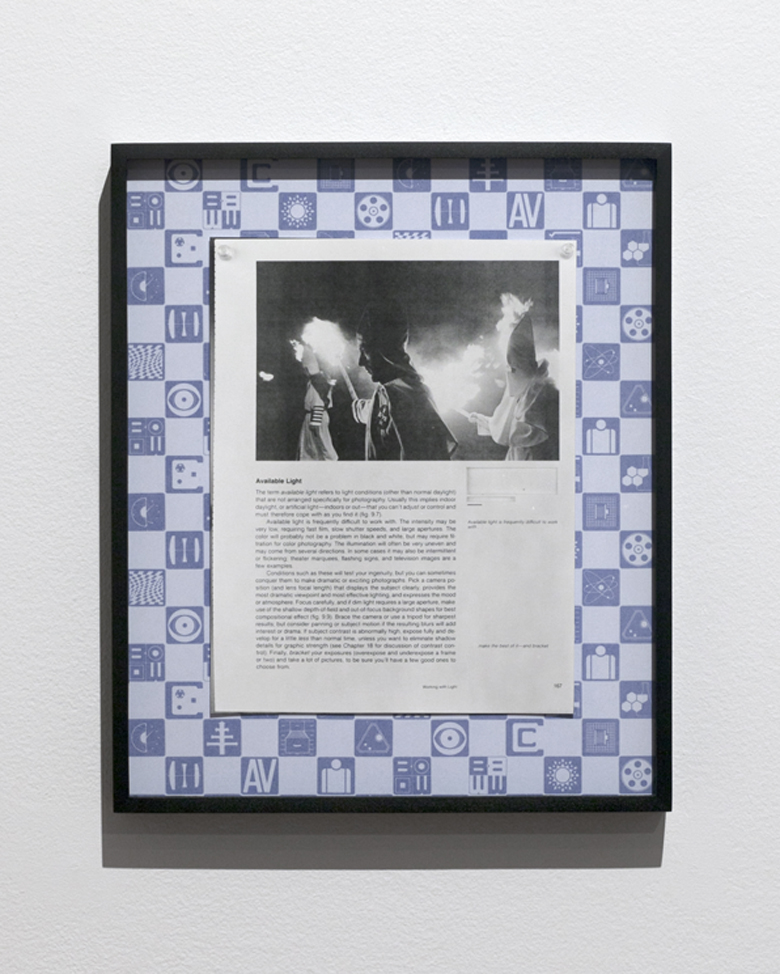

Directly ahead of the viewer on entering the exhibition is a framed page torn from a photography manual defining and explaining the use of available light. The page is illustrated with a photograph of a nocturnal KKK torch lit march. This floats on a pattered blue paper covered with repeating emblems… atoms, a film reel, camera bellows, an eye, etc. rendered as high-modernist glyphs. Is this the endpapers or cover of the photography handbook from which the page is torn? The mid-century glyphs contrasted with the KKK rally image evoke ambiguous memories of the past century. The notion of “available light”—the apprehension of the observed image—seems to be a metaphor for disclosure, occlusion, and even criticality, as pertinent to the other works in the installation as it is in this piece.

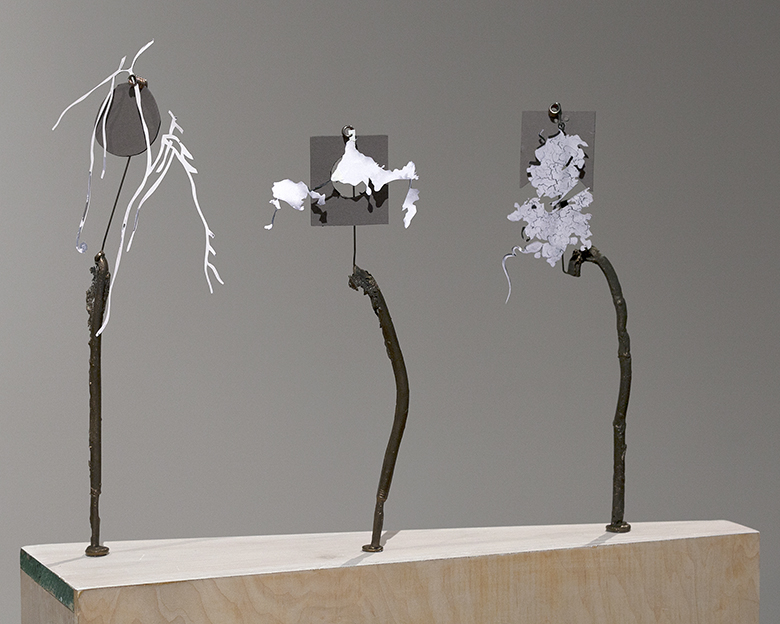

Two untitled works—Untitled (unravel - front) and Untitled (unravel - back)—resembling rayographs present fragments of twigs and vegetal debris. While appearing to be contact prints, they are digital ink jet prints, trifling with the viewer’s art historical assumptions and punning the digital transformation of photography’s legacy dating back to Fox Talbot’s botanical contact prints. A chest-high plinth of birch plywood stands off-centre in the space. Mounted on the plinth are bronze casts of twigs, listed as 4. Untitled (smudge) on the checklist. These rather solid twigs in turn support wires from which paper cut-outs in the shapes of lightning and clouds tremble in subtle response to one’s steps on the floor. As one moves around the ensemble, the solidity of the plinth is visually undermined—the panel one expects to find on the reverse side found absent. An unexpected hollow reveals the forms construction, compromising any expectations of a consistent form.

Photography once had the inherent possibility of arresting the viewer’s wandering attention, now largely lost by the dizzying ubiquity of photographic images.

These pieces and the eleven mostly small-scale components of Miner’s installation comprise a witty and thoughtful oscillation between the ephemeral clutter of the studio with the high art signifiers of ‘finished’ works. This delightful and thoughtful installation presages a high standard of Neutral Ground’s renewed commitment to its exhibition programming. As I stand to leave, almost tearing myself away from the repeating loop of the withered leaf projection, I am puzzled why I have found it the exhibition so entrancing, lyrical, amusing, and even oddly heroic.