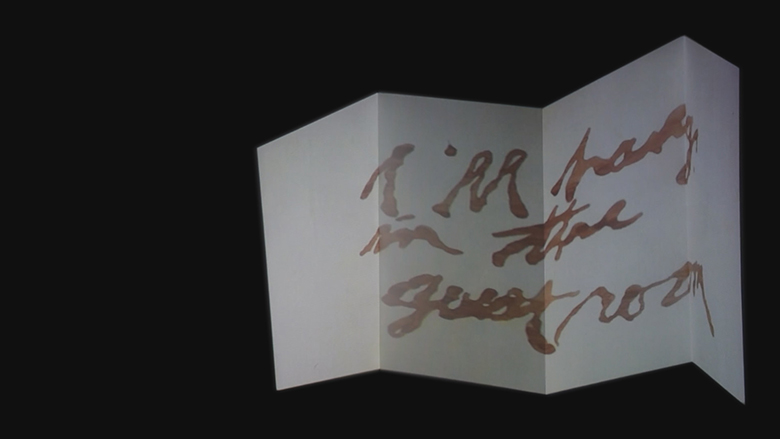

It’s the end of November. Nicole Kelly Westman, Ashley Bedet, Areum Kim, and I drive out to Wayne, Alberta in the dead of night. A map of the site, drawn for us by Nicole, sketches out the trail we will follow, identifies important landmarks and hurdles to be avoided, and strings together a narrative that we will enact together. I keep the drawing and think of it as a coded message, a mnemonic device, and a premonition of what is yet to come. Crossing the Rosebud River nine times in the dark, we arrive to find that we are the only guests booked into the Rosedeer Hotel. Alone and left to our own devices, we cautiously explore the second floor, seeking out any evidence of the ghosts that haunt the halls of the over one hundred-year-old building. We are looking for signs of a woman that was brutally murdered by a group of miners, or so we are told, but we are also hoping that we don’t find any.

A door that leads to the third floor of the hotel is closed with a rusty padlock. We peer through the windowpane and someone points to a piece of cloth that has been pinned up as a window covering. It is moving ever so slightly. Nicole recounts for us second-hand stories about the hotel, saloon, and former coal mining town; how Wayne used to be called Rosedeer, but was changed to the name of the man who was receiving mail for the hotel after being consistently confused with Rosebud, Red Deer, and other towns; how the mine hired members of the Ku Klux Klan to drive out communists, and they burned crosses on peaks within the coulees. The region was nicknamed “Hell’s Hole,” and the saloon was affectionately called the “Bucket of Blood.” The last stop on the train line, Wayne was the dumping ground for stragglers and bootleggers, who were then stranded in the valley until the next train arrived four days later. That first evening, we find ourselves outside and we start a fire near the river, but don’t last long, our ears pricked by the cries of coyotes and the crunch of snow just outside of the fire light.

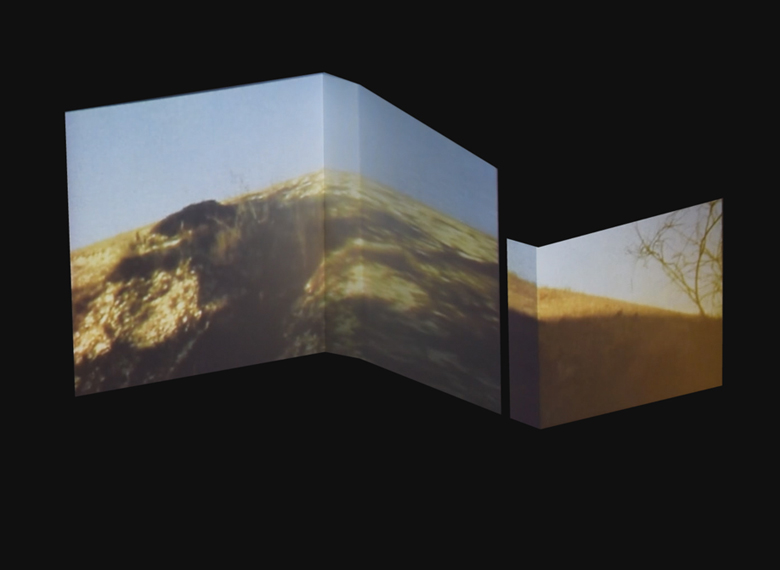

The following day, we drive and walk the valleys of Wayne, Nicole collecting and adhering pieces of the past with the present on Super 8 film, way-finding through intuition and by connecting us, her protagonists, to the land and its many spectres. Nicole is shooting four rolls of Super 8 to be incorporated into her forthcoming visual and media arts installation at the Eric Harvie Theatre at The Banff Centre, Banff. The installation, which is titled Rose, Dear, is a continuation, a third chapter, of two other multi-year projects that address the context of mining, one relating to Pine Point and the other to British Columbia’s Centre of the Universe. For Rose, Dear, Nicole captures a series of non-linear vignettes: a woman treads up a gravel road and passes through an overgrown graveyard, a group of deer scatter and disappear over a mesa, two women flag down and enter an unknown automobile, one walks across a frozen river and through a set of blinding high beams. Through sequences that feel like dreaming, Nicole captures iterations of the landscape, fragments of disconnected narratives, compiling a textured and layered embodiment of place, time, and the spectres that haunt them.

Narratives relating to the cultural, historical, and physical spaces of mining are not unfamiliar territory to Nicole. A family history steeped in the mines of Pine Point, Northwest Territories, Nicole has inherited a wealth of knowledge and understanding about living and dying in these kinds of places; a familiarity with the ghosts of industry and commodity. These same ghosts haunt the hoodoos and coulees of Wayne, terrain marked by natural resource exploitation, deserted save for the declining communities and largely seasonal tourists whose numbers wax and wane as time passes.

An industry that is known for its uncertainty and volatility, for busts and for booms, mining and natural resource extraction significantly alters the landscapes and communities it implicates, often unravelling them into economic collapse. Such is the case with Wayne, Alberta. At its industrial height, Wayne was at the epicentre of coal mining in North America, with a population of almost 3000 in the early twentieth century. Now, decades after the mines were closed in the 1950s, Wayne is a shadow of its former self. Just some thirty residents remain, accounted for in that old-fashioned way popular of ghost towns, on a swinging sign that marks the limits of the community. About ten kilometres southeast of Drumheller, across eleven narrow wooden plank bridges, and deep in the heart of the Alberta badlands, Wayne is mostly deserted, sparsely populated by farmhouses and abandoned machinery, with the last bastions of its industrial past looming in the shapes of the Rosedeer Hotel and Last Chance Saloon, relics of a wild west mentality. The walls of the Saloon record time like the strata of the badlands themselves: lined with newspaper clippings that recount local mythology, objects mined from the homes and lives of previous owners and residents, and a few stray bullet holes. Deep time and human time coexist here in an unsettling way, spectres of absence haunting what has been extracted, what has been left behind, and what has always been.

A visiting artist once told me that the badlands reminded him of a lunar landscape. Another friend has remarked how they relay a sense that, really, the earth is just a big rock, and how miniscule and human that makes her feel. To me, descending into the valleys of the badlands feels like time travel. Layer upon layer of sedimentary rock; textures and tones that demarcate geological time; deposition and erosion, deposition and erosion.

Ostensibly without its own purposes or meanings, the earth is instead framed in relation to the purposes and meanings of capitalism, industry, and progress.

In 1788, James Hutton’s Theory of the Earth expanded contemporary understanding of geologic time through the careful cataloguing of strata and the positing of some of the core tenants of geology. Hutton identified the natural actions that we see in present time (rivers, volcanoes, waves, etc.) as the primary forces that slowly sculpt the earth’s surface over millions of years, creating mountains, valleys, canyons, continents, and seas.1 Hutton unearthed a geologic time that can be plainly observed in the landscape of the Alberta badlands. Descending the steep slopes into canyons of remarkable depth, deep time is delineated through layering, tonal variation and hues that change with the movement of the sun. Seams of sandstone, mudstone, and coal, interlaced with shale, count backwards 70 million years. An unfathomable timescale, the rolling coulees of auburn and copper, which carve jagged lines across the horizon, and the monochromatic hues confuse the senses, and depth, scale, and time slip easily away. It feels natural to yield to the seductive pull of the curves and valleys and to forget that just below the surface exists another narrative, the legacy of coal mines long abandoned.

Mining and extraction imitate geomorphic processes, they take away and they put back, though their means are much quicker and more drastic than geologic time. In 1994, earth scientist Roger Hooke set out to measure and assess the impact of human activities like mining and agriculture on the earth’s surface. His findings had a significant impact on our understanding of how humans shape the world around us and instigated much debate on the topic of anthropic modification of the landscape and subsequently, our climate. Hooke determined that over the last 100 years, humans moved more sediment than classical geomorphic processes. As a geomorphic agent, human activity had eclipsed natural earth processes and moved more earth than glaciers, plate tectonics, wave action, and wind processes combined.2

An anthropic force, human activities subvert geologic time. The timescales of human experience, economics, sociology, and geopolitics, work like nimble fingers to undo and to accelerate geologic time. Situated within the language of mining and those human activities that drive its over-utilization, the earth’s surface is coded as resource, as tool. Ostensibly without its own purposes or meanings, the earth is instead framed in relation to the purposes and meanings of capitalism, industry, and progress. Extraction proceeds as exploitation, creating new landforms, making visible geologic time, unearthing ghosts in the process.

Temporality and the making visible of time are notions of particular relevance to the Super 8 film system, Nicole’s primary method for documenting our time spent in Wayne. Super 8, even more so than photography, requires time as a prerequisite to existence. While the act of photographing produces a representation of a time, a space, and a place, film is a medium perceived in time. While both media share time lapses of documentation, exposure, and presentation, the projection of film invites an experience of time that is self-conscious, and that contains a sense of unfolding temporality. Developed in the 1960s, Super 8 shoots on an 8-millimeter width film stock at 24 frames per second, capturing only 3 minutes and 20 seconds per cartridge. A physical and conceptual limitation, shooting Super 8 requires planning, intuition, and luck. Without the luxury of playback or any guarantee that it will turn out as expected, film creates suspended time, distended until the moment it is developed and reviewed, long after the initial impulse to record has passed.

Affective, overly saturated, and grainy, Super 8 captures a fragile and detached apparition of the world, bound inherently to the apparatus of filming, the videographer’s subjectivity, and a perceived past. The low resolution, the glitches and textures, and the dreamy painterly quality connects Super 8 film to the realm of nostalgia and consequently, to a psychological purpose of signifying and suppressing time by connecting to lived time: an authentic past to a present. For Super 8 film shot in the present day, the authenticity of this signification is a simulacrum, a constant loop between now and then, an ephemeral timelessness. For Nicole, this contradiction is key, connecting our lived bodily experiences of the land to its infinitely entangled past iterations and echoing the slow patient movement of geologic time through photographic tools of yesterday.

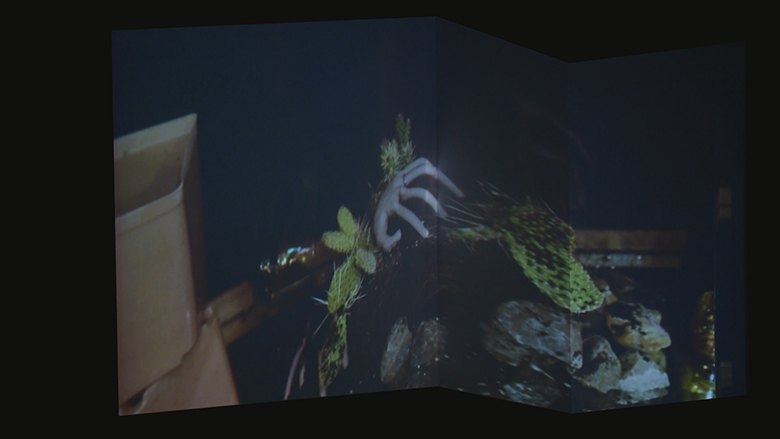

Rose, Dear is a compilation—of moments, concepts, and relationships—executed through a moving collage of digital and analogue film techniques including Super 8 and digital footage, animation, and slide film; an archival chromogenic print of historic Wayne on loan from the Rosedeer Hotel; a hauntingly crescentic audio composition; and sculptural elements that reference physical and conceptual relics of film and photography. Objects and performative actions are tasked with both divining and initiating dialogue between the past and the present. Ancient rocks are carefully arranged, prickly pear cacti are lovingly caressed by clay hands, a geode is broken and its precious orifice examined. Far from submitting tacitly, however, like the landscapes where they originate, their task is to reveal their own narratives, their own hauntings.

Our task, winding throughout the various gestures included in Rose, Dear, feels like reclamation, like making visible the ghosts that are conjured in the course of industry, capitalism, and exploitation. Momentarily captured on Super 8, we are the women who haunt. We haunt the curves and bends of the landscape, we haunt spaces damaged by physical and conceptual injustices, we haunt geologic time uprooted through industry. A riposte to the parallels between climate crisis, global economic models, and the ongoing exploitation and disempowerment of women and others, we carry out performative actions for making visible the tensions of fractured places, of places of oppression. We cultivate a reciprocal relationship with the hills and valleys, we acknowledge the ghosts that live here and we add our own, entangling our actions with those fashioned and disturbed by place, time, and industry. A poetic interference in the narratives of abandoned places, Rose, Dear offers intra-active methods for communicating with their ghosts, in the hopes of both reciprocity and revelation.

Rose, Dear opens to the public on February 10th, 2016 and runs until June 5th, 2016 at the Eric Harvie Theatre—Lobby West, at The Banff Centre, Banff.

Nicole Kelly Westman is a visual artist of Métis and Icelandic descent. She grew up in a supportive home with strong-willed parents—her mother, a considerate woman with inventive creativity, and her father, an anonymous feminist. Her work culls from these formative years for insight and inspiration. Creating work that exists beyond the binaries of a specific medium, Westman finds inspiration through the plumbing of archives and through deep research. She has had the pleasure and privilege to be curated into exhibitions by remarkable females including: Ginger Carlson, Peta Rake, Kristy Trinier, and cheyanne turions. Westman holds a BFA from Emily Carr University and is the current Director of Stride Gallery, Calgary.