Against an ominous and jarring soundtrack, a man says, “So I went to a psychiatrist and he told me that I was a woman trapped in a man’s body.” On the next screen, we see actor Leslie Neilson reacting with surprise as he discovers that the woman who has just undressed before him has a penis. Her body is shown, complete with flaccid penis and breasts, as a shadow upon the wall. Neilson covers his mouth and runs away as if he is about to vomit. On the third screen, the camera pans across a body lying on the floor, wearing high heels, boxer shorts, and what looks like pyjamas, and a robe. The camera stops on a trans woman’s face. She appears to be in a great deal of anguish and, as the subtitles indicate, she is crying. A wig, seemingly torn off her head, lies beside her in a dishevelled pile.

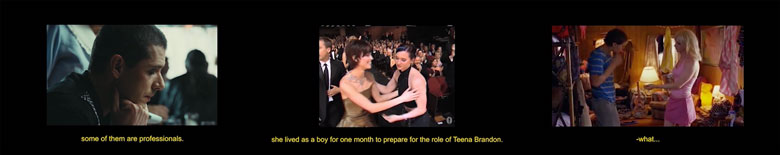

These are some of the first images and snippets of dialogue from B.G-Osborne’s ten-and-a-half-minute 2018 video installation A Thousand Cuts. Appropriated clips of representations of trans people played by cisgender actors from 48 films, 34 television series, and one music video are interspersed between three monitors. While the source materials range from as early as 1953 up to 2015, the majority of the clips are from the 1990s and the 21st century.

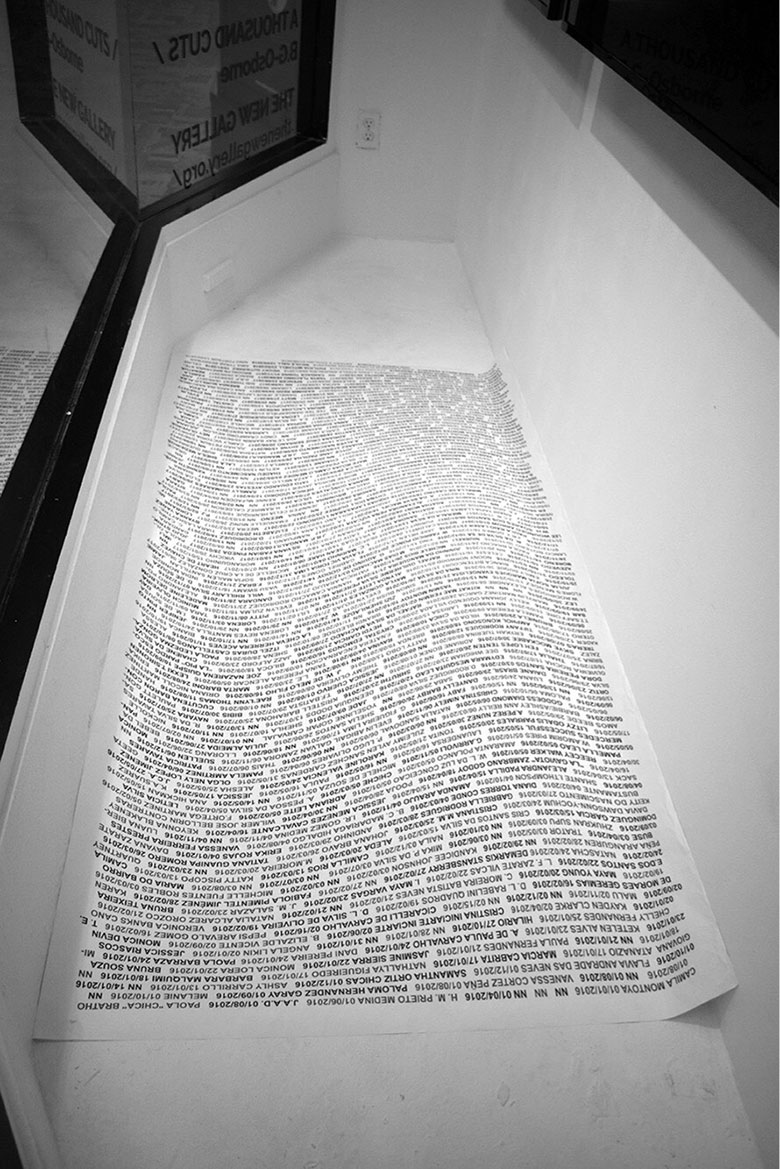

The installation also included a list of all the documented trans people who have been murdered in the last two years.1About including the list, Osborne said, “I wanted to contrast the misrepresentation of trans people with the often-harsh reality of trans existence: a reality that is seen as normal to cisgender people due to our misrepresentation in film and television.”2The length of the list is devastating.

In their artist statement Osborne asserts, “the work confronts transgender cinematic tropes and the erasure of transgender people in mainstream media…A Thousand Cuts creates new meanings through a crescendo-like composition ranging from humorous to violent.”3The work is certainly disturbing and it is meant to be. It acts as a mirror of the rampant transphobia and violence against trans people in our contemporary societies. According to Osborne, “The title of the work comes from the phrase Death by A Thousand Cuts, which refers to a slow, cumulative process in which bad things keep happening until the point of destruction. I drew a connection between this phrase, anti-trans violence, and the physicality of film as a medium.”4The appropriated clips demonstrate how trans characters within popular culture are far too often inappropriately represented as punch lines, threats, deviants, unnatural, and dangerous.

A clip from an episode of the TV show Friends shows a woman performing on stage. The scene cuts to her son Chandler who says in an angry and sarcastic tone, “And there’s Daddy!” The laugh track blares as his fiancée Monica looks utterly shocked. In the film Zoolander 2, in response to a gender non-binary model saying that they are not “defined by binary constructs”, actor Owen Wilson says: “That’s cool. I don’t like labels either. But I think he’s asking do you have a hotdog or a bun?” Many of the clips poke fun at the idea of transitioning and gender reassignment surgery. The straight cis male characters seem to be particularly obsessed about whether these trans women still have penises or whether they have had bottom surgery, which is presented as necessary to become a “true” woman. In a number of clips straight cis men are either disgusted or become violent upon discovering that the women they desire have not “fully” transitioned.

Edmonton trans writer and artist Alexa Thompson discussed her reactions to A Thousand Cuts, “A lot of the examples played it for comedy. Either it's funny because men are worth more than women, so, he is debasing/embarrassing himself by presenting as female. Or the transgender character (often unintentionally) ‘tricks’ the lead into thinking they are a ‘real woman’. Nothing that follows that moment is ever good. Another common reason for a transgender or non-binary person to show up was to indicate they are psychotic. An obvious sign of mental illness.”5Thompson said about the negative impact of these types of representations, “I've had issues with how transgender and non-binary people have been portrayed in film and television forever. It prevented me from exploring who I truly was, and resulted in some behaviour that was damaging to myself, and others.” Some of the clips in A Thousand Cuts express both transphobia and homophobia. In one clip a man becomes violent towards a trans woman. He screams at her, “Why didn’t you tell me you were pre-op, you should have told me! I don’t want a girl with a dick, ok? I’m not gay, ok. I’m not into that.” There is also a great degree of horror expressed in many of the clips at the idea of “having it cut off.”

All of these mainstream representations of trans characters fail to recognize that genitals do not necessarily equate with gender. There are certainly many trans people who actively choose to not have bottom surgery and yet they are still just as much of a man, woman, or gender non-binary person as anyone else. The 2018 documentary Beyond the Opposite Sex (not included in Osborne’s mashup), Arin, who identifies as a gay trans man, chose to have top but not bottom surgery. He says “I never changed, I just confirmed. I confirmed who I was when I transitioned.”6Ari is asked, “So you haven’t fully had your surgery?” and he responds, “I don’t like to use the word fully because for me there was a point where I was like, I’m just going to be okay with it. Someone can be with someone because you are a male not because of what’s in your pants.”7In one of the last clips in A Thousand Cuts, a young man reaches into the skirt of the young woman he is making out with. He withdraws, confused, and asks, “What is that?” She responds, “It’s what I have to work with.” These are the last words spoken in Osborne’s compilation.

This is not your average video mashup. Unlike more typical, easy viewing mashup compilations, the editing in A Thousand Cuts is purposefully not seamless and the supposed humour is presented with a critical edge. The movement between the different clips is frenetic, chaotic, and unsettling, quickly jumping from one clip to another. The clips overlap at times to such an extent that it becomes difficult to take in the dialogue and images on all three monitors at once. The music is often foreboding, destabilizing, and suspenseful, similar to a horror movie soundtrack. Rather than constructing an easy to digest narrative, there is an overflow of information and it takes a few viewings to unpack the details. This overwhelming viewing experience is very effective in that it replicates the bombardment of misunderstandings, misconceptions, and dehumanizing representations we see about trans people in the media every day. Osborne said, “The creation of A Thousand Cuts has been a slow process, and I do not consider it ‘finished’. I have spent two years on-and-off acquiring video footage, editing, synching, subtitling, talking about the work with peers and strangers, and brainstorming larger installations.”8

Thompson praises Osborne’s work, “I never felt that I saw someone like me represented on screen until I saw Sense8.9A Thousand Cuts shows just how rare a truthful portrayal is. This work made me angry, sad, helpless, and empowered. I had to start and stop it a couple times to compose myself. It is an incredible work that encapsulates a large part of the trans experience, using imperfect source material to create an experience that is truthful and gutting. For empathetic cisgender people, I think this would function as a bit of a ‘transgender simulator’. I can see why it made people uncomfortable. Being transgender is uncomfortable. I had high hopes for A Thousand Cuts, and they were surpassed. After three viewings, I still tear up at the last line.”

"Trans people are still being murdered at a seriously alarming rate, misrepresentation will continue to happen in mainstream media, we will try to take back our image and tell our own stories, cisgender people will keep being offended, and we will keep fighting."

Infuriatingly, A Thousand Cuts was censored in September 2018 by Arts Commons a multi-purpose arts facility, who oversee the 15+ window exhibition space in downtown Calgary where it was displayed. According to the New Gallery website, “The reasons cited being that the work contained ‘a lot of swearing and nudity’ that had garnered ‘a lot of complaints from concerned patrons.’”10From multiple viewings, the only nudity I saw was the illusion to a naked body as a shadow on the wall in the Neilson clip and the inclusion of swearing was an integral aspect in the meaning of the work. Arts Commons programming director Jennifer Johnson, stated, “We think it [the artwork] carries a valuable message and has been created with love and care…This was simply not the appropriate venue for the piece.”11In their letter in response to the censorship Osbourne said: “It is ironic that a video compilation that highlights the far-too-common act of cisgender actors being permitted and feeling entitled to play trans characters in film and television, is too offensive when looked at through a critical/ trans-lens...Trans people are still being murdered at a seriously alarming rate, misrepresentation will continue to happen in mainstream media, we will try to take back our image and tell our own stories, cisgender people will keep being offended, and we will keep fighting.”12

The New Gallery, who selected and exhibited the work, offered a number of accommodation options such as “the placement of a QR code in the vitrine allowing viewers to access the video on their phones, placing a copy of an open letter Gilmer-Osborne wrote about the video in the vitrine, turning down the volume on the video, and running the video only after school-group visiting hours end at 3 p.m.”13The Arts Commons refused these options and offered to show the work for one night only at an alternative venue. This option was not amenable to the artist or the New Gallery. Five Calgary artist-run centres have since announced they will no longer be programming work with Arts Commons or in the 15+ Window spaces.14Osborne states, “If you/your organization censors work by a trans artist (and it has been noted that they have censored work by a trans artist before me), then you/your organization is transphobic, or at the very least displaying transphobic behavior. A Thousand Cuts did not warrant this censorship, but it solidified the notion that a lot of people are scared of trans bodies/representation when it is in the hands of trans people (even though the video compilation had no actual trans people in it!)”15

The video work, A Thousand Cuts was installed at three alternative venues: the University of Calgary Art Department (Calgary, AB), Latitude 53 (Edmonton, AB), and Left Contemporary (Windsor, ON). For more information and statements, go to http://www.thenewgallery.org/a-thousand-cuts/.

B.G-Osborne is a Transmedia artist from rural Ontario, currently working in Montreal. Their work focuses on exploring and interrogating the potential of gender-variant embodiment to serve as both a tool for gender deconstruction and revision. They graduated as valedictorian from NSCAD University in 2014 with a BFA in Intermedia. Osborne’s ongoing projects seek to address the complexities of trans representation and violence, mental illness, and family secrets/stories. They place great importance in showcasing their work in artist run centres and non-commercial galleries throughout Canada.