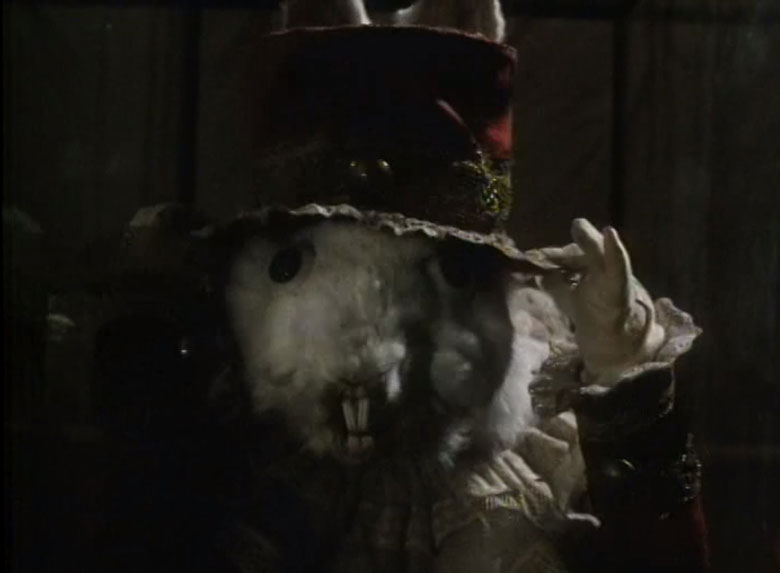

Dolls, string, keys, tins cups, taxidermy, glass eyes, wooden mushrooms for darning, and socks make up the cast of characters in Czech animator Jan Svankmajer’s 1988 feature length film Alice. It is as if these objects, similar to those found in junk drawers in many homes, came alive through the process of animation.

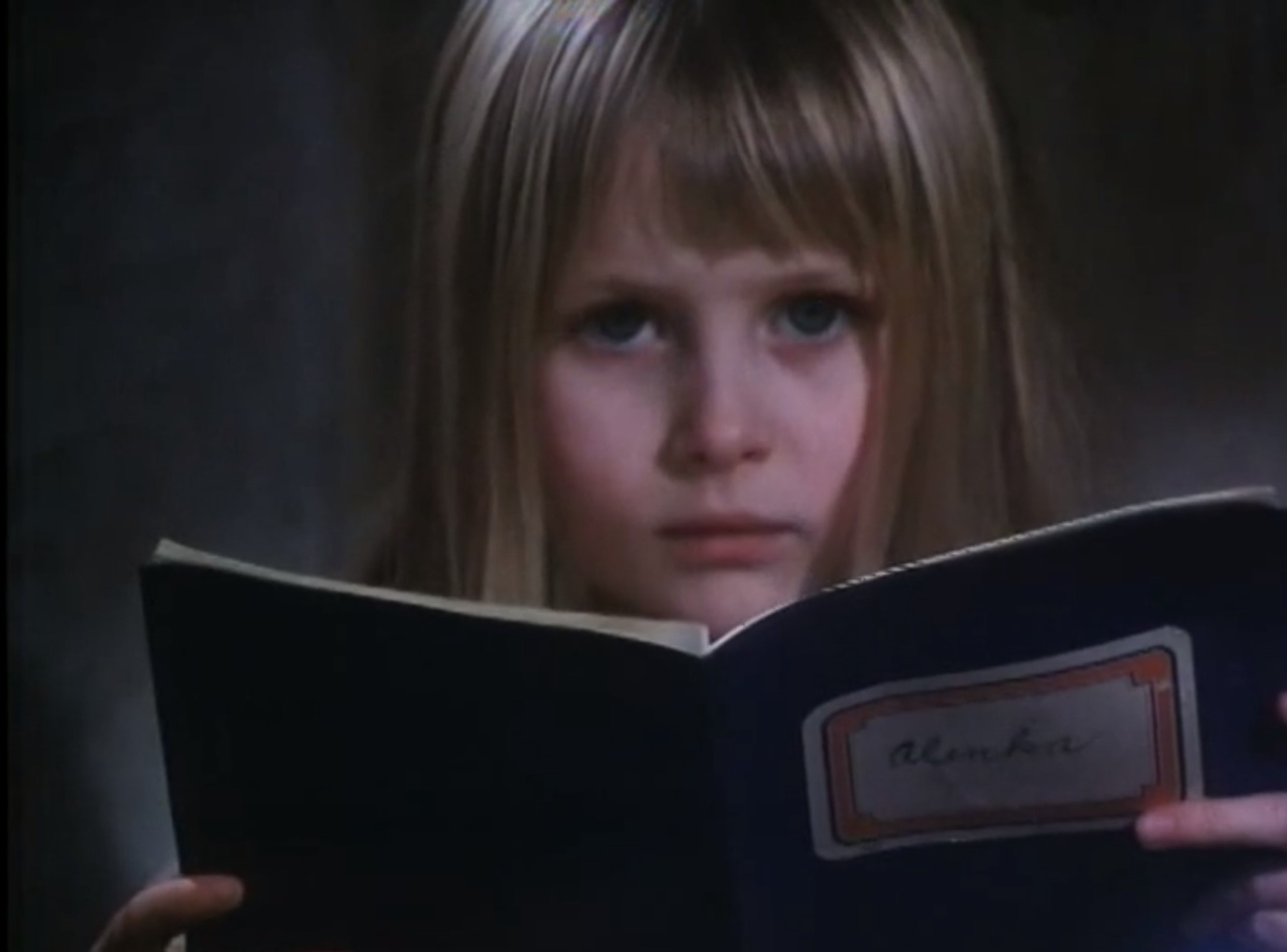

The character of Alice (Kristýna Kohoutová) appears uncomfortable in the real world. The film is an expression of frustration at a system that forcefully tries to fit a person into a certain shape or box. She doesn’t feel as if she belongs, so she violates the social norms of her house. Throughout the film, Alice is confronted with creatures telling her she doesn’t fit in, or that she is doing something wrong. The opening sequence establishes this, as Alice, distracts herself by throwing stones into the middle of a river. When she attempts to touch a book resting on her companion’s lap (perhaps she is curious of how the pages feel when she flips through them) a hand slaps hers away, and she sulks. Rather than hold the book, she must remain at a distance. Look but don’t touch! But Alice wants to play.

Alice is a blend of live action and stop motion animation. Stop motion and traditional drawn animation are both created out of many independently produced frames, drawn or assembled. In drawn animation, the figures are animated on one or more flat planes. In cel animation, for example, there is a background layer, and various panes of glass on which the animators add drawn or painted figures, perhaps even other layers of background to add the illusion of depth. Stop motion, which often includes the orchestrated movement of three-dimensional objects, does away with the planes and is closer to live action in its use of space. The stop motion animator can build sets and sculpt the figures and actors. In Alice, Svankmajer both creates and uses found figures objects including socks, string, glass jars, glass eyes, taxidermy animals, and dentures. In earlier works, he only used clay, allowing for complete and utter control over the figures’ shape and appearance. The use of an assortment of found materials in Alice transforms the characters in unsettling, uncanny ways.

Svankmajer describes a dream “as an expression of our unconscious, uncompromisingly pursues the realisation of our most secret wishes without considering rational and moral inhibitions, because it is driven by the principle of pleasure.”

In the second scene of the film, we see a collection of domestic tools populating the shelves and floor of a house. Alice explores, what we can only assume to be, her own house. She witnesses a taxidermy rabbit pull nails from its paws and smash its glass tank with scissors. The rabbit runs off into a flat, brown, outdoor area with a side table standing in the middle of it. The shot of the rabbit makes the outdoor space appear within the house itself. From this moment, Svankmajer clarifies that this house knows no bounds. The side table turns out to be the entrance to Wonderland, and Alice climbs inside an impossibly small drawer. The household objects repopulate the world of the drawer, animated and alive. Just imagine if, instead of farmhands in makeup and costumes in The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy skipped across the yellow brick road with a set of kitchen utensils with glass eyes, a stuffed cat covered with seams, and a man made of various squash wearing a straw hat and overalls.

Calgary’s Giant Incandescent Resonating Animation Festival (GIRAF) screened Alice on November 23, 2018. A loose adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s 1865 literary classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Svankmajer’s film shares the author’s concern with nonsense. Both feature scenes of a baby morphing into a pig, the mad tea party, and the red queen’s croquet game. Alice, unlike the original text, keeps dialogue to a minimum. Carroll’s Alice comments “Curiouser and Curiouser” about the spectacles she witnesses.1In contrast, Svankmajer’s Alice stares silently, as if she were resisting these wonders, denying them their strangeness by refusing to comment on them. At most, she calls to the rabbit to wait, and later defends herself when she’s accused of eating a plate of tarts. However, Alice herself supplies all the other voices. Whenever another character speaks, Alice performs their lines, and narrates with a close-up of her mouth saying “said the white rabbit,” “said the mad hatter,” “said the caterpillar,” and so on.

Svankmajer’s film is a free adaptation, opting to rely on visual nonsense rather than the original’s verbal nonsense. Carroll’s Alice strives to get home in the end, back to Dinah and the poem she must memorize while Svankmajer’s Alice wanders with only a small goal, to follow the rabbit, and ignore her school homework. Svankmajer includes his own surreal scenes, such as a pile of leaves flying into a drawer after Alice delves into the rabbit hole, loaves of bread which spontaneously sprout nails, and the trial of the tarts being scripted with booklets identical to Alice’s homework.

Alice shares only a few aspects with the well-known 1951 Disney film adaptation, which also mixes in some of the characters from Carroll’s 1871 sequel Through the Looking-Glass, such as Tweedledee and Tweedledum. Svankmajer stays strictly within the events of the original Adventures novel, aside from his own additions. Disney’s Alice character enjoys going through Wonderland, with wide eyes and delight, she sings with the flowers and listening to the story of the Carpenter and the Walrus. Svankmajer’s Alice always has an expression of indignation and determination on her face. She is a rebel, not a tourist.

Svankmajer’s Alice chases the white rabbit without an end in sight. This chasing of desire ties into the Freudian notion that dreams are about wish fulfillment. Where many filmmakers represent Carroll’s story as a fairy tale, Svankmajer sought to portray Alice as if she is wandering in a dream.2Svankmajer pursues the creative potential of dreams in most of his work. He remains a member of the Czech Surrealists, which he joined in 1970, to this day.3The aesthetics of dreaming, are his specialty. Take Svankmajer’s 1971 short film Jabberwocky, his first Lewis Carroll adaptation from the poem of the same name, consists of a reading of the original poem, with a series of events that seem tangential to the poem’s content. We see non-linear, surreal images such as erratic trees blowing in the wind, a wardrobe that skirts around the forest, and a schoolboy uniform dancing without the aid of a boy to wear it. These images are odly are fitting, as Jabberwocky’s first line reads “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves / Did gyre and gimble in the wabe”.4Who really knows what those two lines mean? Because of the made-up words, Svankmajer’s guess is as good as any.

Svankmajer’s Alice always has an expression of indignation and determination on her face. She is a rebel, not a tourist.

Svankmajer describes a dream “as an expression of our unconscious, uncompromisingly pursues the realisation of our most secret wishes without considering rational and moral inhibitions, because it is driven by the principle of pleasure.”5Thus the unsettling process of breathing life into the figures in Alice is like dreaming. Similar to the stop motion animator picking up a darning tool to create a mushroom, dreams re-appropriate material gathered throughout a person’s life, and transform them into new narratives. Svankmajer’s figures look as if they are so tentatively constructed that they might fall apart at any moment: the white rabbit’s eyes threaten to pop out of their sockets, the caterpillar’s dentures are held tenuously by the frayed edges of a hole, and the skeletal animals which aid the rabbit have limbs clearly taken from other animals. The figures are collages in the open. Svankmajer makes no effort to hide the seams, and so calls attention to the falseness of the world, creating a sensation that the viewer, and the dreamer, could wake at any instant.

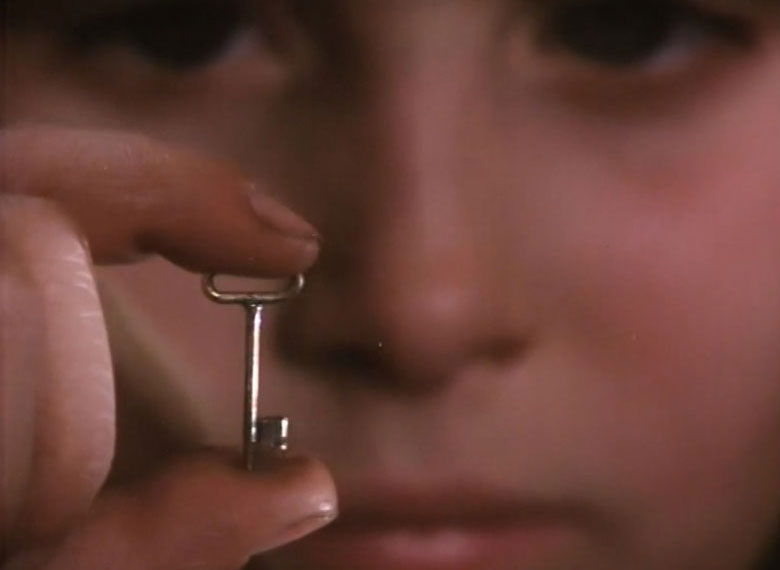

The Victorian-looking kettles, large brass keys, stopwatches, archaic playing cards in the film are all objects we still use often, but versions of which that have faded into obscurity. Svankmajer’s fascination with the sense of touch is seen all through his career, as with his art experiments with touch6and Alice is no exception. The sound design of the film and the objects work together to evoke tactility. Since stop motion does not have any sound whatsoever, all the sounds present in the film are added after the fact. Without a soundtrack per se, the film’s soundscape has a richness that does wonders. The cracks, thumps, and snaps; the clicking of the clocks; the grinding squeak whenever the rabbit moves; the thumping of drawers closing; the tin pots ringing; all contribute to the film’s rough texture. The viewer is encouraged to look for how he pulls off the magic tricks onscreen. Viewers know that socks cannot slip from a person’s feet and burrow a hole in the floor, yet we are led to believe it to be true when Svankmajer shows us exactly that. In this sense, Svankmajer alienates us from a sphere of life that is most familiar.

The film reflects the life of children in a sincere way: how, as kids, we wander a world which does not behave as expected, with constant surprises around every corner.

Since Alice proclaims at the beginning that this is for children, it challenges them to see everyday objects as more than what they appear to be. Perhaps the darning mushroom really is also a mushroom. Maybe the socks are caterpillars too. There is an internal, bizarre logic to the filmaker’s decisions as well. Why is the rabbit full of sawdust? Well, he isn’t dead, that’s certain, so it must be because he eats sawdust. This is the sort of play which Svankmajer invites: a re-imagining of the world we see day-to-day, opening it up to new possibilities. The film reflects the life of children in a sincere way: how, as kids, we wander a world which does not behave as expected, with constant surprises around every corner. The fact that Wonderland is the inside of Alice’s house transformed into a dream world, reflects that as children, the boundaries between dreams and reality, what we see when we open or close our eyes, is blurry.

Svankmajer creates a film which invites you to see a well-known story in a new light, like the assortment of curiosities created from a domestic household. Alice herself struggles against the various creatures she encounters, trying to catch up to the white rabbit. At the film’s close, taking up the rabbit’s scissors, she might have.

The 30th anniversary screening of Alice was held on November 23, 2018 as part of the GIRAF Festival of Independent Animation at the Globe Cinema in Calgary, AB.