As far as Western Canadian dramas go, the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike is a compelling one: tens of thousands of striking workers on one side, police on horseback on the other. The mayor reads the Riot Act and two workers are killed by police on a day that has come to be known as Bloody Saturday. In many ways, it’s a moment in history that seems made for the cinema. However, it’s also a challenging moment to portray. History books have favoured certain narratives of the strike over others and particular moments have entered the realm of folklore. This has made it difficult to ascertain which version of the Winnipeg General Strike story to believe.

It’s a surprisingly slippery story for such an important moment in Canada’s labour history, but that hasn’t prevented filmmakers from taking a stab at telling the strike story over the years. Some of these films include the following: the 2001 documentary The Notorious Mrs. Armstrong by Paula Kelly; Guy Maddin’s My Winnipeg from 2007; Noam Gonick’s 1997 short film 1919; and Danny Schur who takes up this challenge in his upcoming 2019 film Stand!

When over 30,000 Winnipeg workers went on strike in 1919, it was less than a year after the end of World War I, only two years after the Russian Revolution, and came on the heels of a general strike in Seattle. There was labour unrest across Canada, and it came to a boil in Winnipeg, then the fourth-largest city in the country. That same year, a commission was established by the federal government to identify ways to improve the relationship between employers and employees, and the commission visited Winnipeg just days before the strike began in May 1919. The commission found that some of the reasons for the labour unrest in the city were the large number of soldiers returning from the First World War, the high cost of living, inflation, and a lack of social supports, especially for the returning soldiers.

Newspapers from across Canada and the United States descended on the prairie city to cover the strike, but according to media historian Michael Dupuis, many of them failed to represent this context.1Instead, many newspapers portrayed the strikers in a negative light and attempted to connect labour leaders with Russian Bolsheviks. This played into the “Red Scare” narrative being promoted by conservative politicians to stoke fears of socialist, labour-affiliated, and other leftist political viewpoints. These newspapers fuelled the divide between the strikers and the city’s anti-strike forces. The tensions came to a head after ten leaders of the strike committee were arrested on June 17. Four days later the mayor read the Riot Act and called in the Northwest Mounted Police, who charged on horseback into the crowd of strikers, killing two people: Mike Sokowolski and Mike Schezerbanowicz.

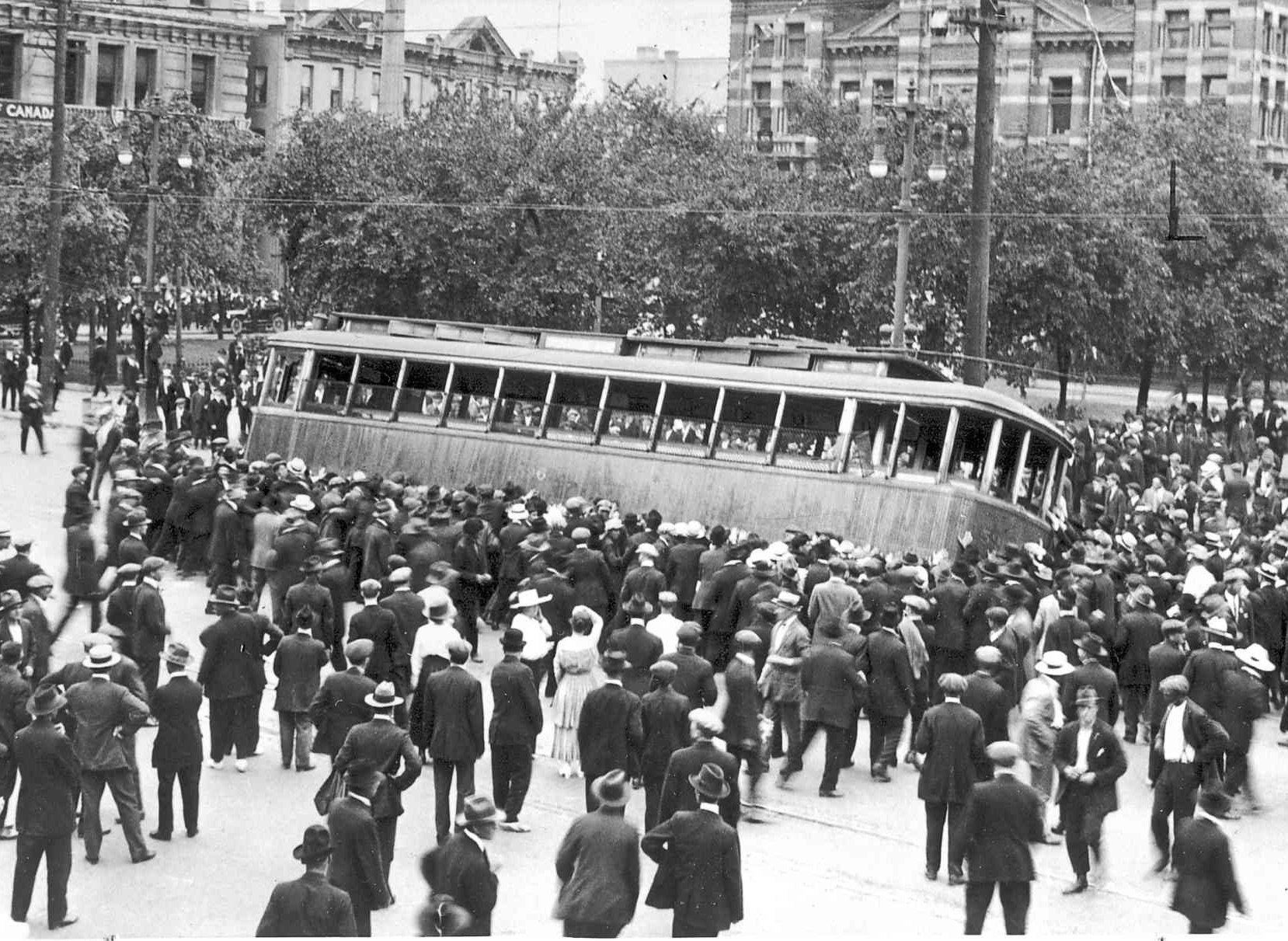

Aside from coverage in newspapers, images were also important at conveying and preserving the events of the strike. Many of the images from that time, such as L. B Foote’s iconic photographs of the strike, remain familiar to many Canadians. Foote is one of the most well-known photographers in Winnipeg’s history, capturing the city’s development for over 50 years.2His black and white snapshots of crowds of workers gathering in the streets of downtown, including one that captures a group of people right at the moment they tip over a streetcar on Main Street, are probably what most people think of when they think of images of the strike.

While Foote’s photos have stood the test of time, films shot during the strike have largely been relegated to obscurity, and many of them have been lost forever. According to Dupuis, a few moments captured by local documentary filmmaker Jean Arsin are the only motion pictures that exist of the general strike. Dupuis calls Arsin a “rare breed” for his day.3Arsin was working as a freelance filmmaker, producing short documentaries and selling them to companies in the United States at a time when few others were. He shot footage of the general strike in the hopes of selling a documentary about the event to the City of Winnipeg. Historical records show that he did indeed make a documentary about the event, and even showed it at the Lyceum Theatre. The film soon got lost as there wasn’t any interest from the city in purchasing it.4Only partial sections of Arsin’s footage that have been digitized remain. One clip shows children riding bikes through a huge crowd in a schoolyard, while another shows people marching and waving their hats through the streets of Winnipeg. These snippets have made appearances in more recent films about the strike, including in Bloody Saturday: The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, Andy Blicq’s 2007 documentary for the CBC.

The mystery around Arsin’s footage reflects a greater difficulty about the strike itself: the challenge of excavating the stories of strikers from a historical record that was predominantly anti-labour. Although the general strike is one of the most well-known events in Canada’s labour history, and perhaps in the history of Winnipeg, there are moments that took place beyond the frame of photographers such as Foote or filmmakers like Arsin. There were many stories that were not covered by local journalists who were preoccupied with vilifying strikers and exaggerating fears of a Bolshevik revolution. Since 1919, numerous films have mined the mystery of the strike by uncovering or reimagining the events and characters of this pivotal moment in Winnipeg’s history.

I’ve been interested in the ways Winnipeg reflects itself to the world ever since I moved here as a teenager, shortly after the release of local artist Guy Maddin’s film My Winnipeg in 2007. A recurring theme in Maddin’s film is the interplay between history, memory, and mythology, and the layers of social and personal history that must be peeled back before one can fully understand this place.5I was enthralled with the way Maddin combined fact and fiction to tell the story of Winnipeg. For a long time after moving here I walked the streets in a dreamlike state — not dissimilar to the sleepwalkers of his film — looking for clues in the buildings and street signs of the stories that I knew lay just beneath the surface.

Although the general strike is one of the most well-known events in Canada’s labour history, and perhaps in the history of Winnipeg, there are moments that took place beyond the frame of photographers such as Foote or filmmakers like Arsin.

In many ways, the attempts to tell the story of the Winnipeg General Strike reflect the same relationship between mythology, history, and memory that are explored in My Winnipeg. The general strike makes an appearance in Maddin’s film, if only for a few minutes. Maddin narrates a reimagining of “the drama of our city’s most glorious moment,” where the strike spills over from the streets of downtown to the streets of Crescentwood, a wealthy neighbourhood where many anti-strike leaders lived. The two groups clash outside St. Mary’s Academy for Girls, “where the quaking little princesses of the middle class tremble out their fathers’ fear of workers.”6The film contrasts depictions of nuns and Catholic schoolgirls with depictions of the strikers as “Bolshevik rapists,” a nod to the fear-mongering and hyperbolic media coverage of the time. “You can feel the spirit of labour still, whenever you walk around St. Mary’s Academic at night,” Maddin narrates. “You can still see the impotent old fence, now snow-buried, that once tried to keep those heroic Bolsheviks at bay.”7

While strikers may never have marched across the Assiniboine River to the gates of St. Mary’s, the spirit of the strike and the ghosts of its participants certainly haunt this city. Despite the countless articles, books, and other historical accounts of the strike, there is still plenty of uncertainty about many details of the strike. For years, Winnipeg playwright and filmmaker Danny Schur has been haunted by one particularly slippery detail about the strike: How did Mike Sokolowski, a Ukrainian immigrant who was killed during the strike, end up outside City Hall on Bloody Saturday, and how did he die?

Schur’s enduring fascination with Sokolowski led him to make a documentary called Mike’s Bloody Saturday in 2011, in which he takes viewers on what he calls a “virtual walking tour through the maze of contradictory evidence” surrounding Sokolowski’s death.8The film asks whether Sokolowski was truly a “revolutionary bent on assassinating the mayor” or rather a “hapless immigrant who was in the wrong place at the wrong time?”9Seven years after making the film Schur says, “We still don’t know. We have a pretty good idea, but it’s not what you think. He was not [of a labour background] and, although sympathetic to the goals of the strike, he was probably not a participant.” Schur says there are hints in some newspaper coverage from the time that Sokolowski was actually a scab (a person who refuses to join the strike or who fills in for striking workers).

For Schur, Sokolowski’s story illustrates the connections between the experiences of immigrant workers living in Western Canada just after World War I, and the growing nativist sentiment around the world today. However, like Maddin, parsing fact from fiction doesn’t seem all too important to Schur. His upcoming film Stand! is a film adaptation of his 2005 hit musical Strike! The film begins with Sokolowski (played by Gregg Henry) trying to earn enough money to bring his family over from Europe. Here Schur blurs fact with fiction since Sokolowski’s family was actually living in Winnipeg at the time. “Our attempt is to make it a parable for today,” he says. “There were just some interesting parallel things that I found from that era, like how some immigrants wrote an open letter to the paper and listed their grievances. It’s exactly like the grievances of every immigrant community today, which is that they’re disenfranchised, they’re marginalized, they’re migrant labour.”10

At the core of Stand! is a compelling love story involving Sokolowski’s son (played by Marshall Williams) and their Jewish neighbour (played by Laura Wiggins). Here, Schur takes the opportunity to address another important issue of that era: anti-Semitism. It was important for Schur not to romanticize Sokolowski’s character at the expense of acknowledging his faults. “He was anti-Semitic as hell,” Schur says. “He didn’t like the fact that his son had taken a shine to the Jewish suffragette who was in their tenement.” The story of Sokolowski’s family sets the stage for an emotional drama that’s only heightened by the fact that it’s also a musical. “Music is trump card,” Schur says. “It allows you to experience emotions like no dry dialogue can.”11

Beyond the change in its name, the movie version will also have some significant changes in plot and characters. Schur says the film’s director Robert Adetuyi convinced him to “put back in the picture the people who previously were not.”12For example, he’s changed the character of Emma from a white Irish maid to a young Black woman who fled to Canada from the Jim Crow era in Oklahoma. Emma’s character is played by Winnipeg actress Lisa Bell, who sings the eponymous song in the film’s teaser. The trailer is campy, as you might expect from a musical. It obviously tries to hit all the classic notes of hardship and injustice surrounding the strike, with the requisite star-crossed love story in the middle. In addition, it offers a glimpse into a side of Winnipeg’s history that hasn’t often been shown on film: Black women discussing their place in the city’s white-dominated labour struggles.

The inclusion of Emma’s character represents a trend in films about the Winnipeg General Strike towards representing marginalized communities who weren’t part of the original strike narrative. “Absences in the historical record are often as compelling as the existing evidence,” writes Paula Kelly about her own 2001 documentary about the general strike.13Instead of the absence of people of colour in historical accounts of the strike, Kelly is referring to the absence of women in these accounts. In her documentary The Notorious Mrs. Armstrong, Kelly brings Helen Armstrong, one of the women at the heart of the strike, “back from the margins of history.” Early into her research for the documentary, Kelly found she had her work cut out for her, as there were only three images of Armstrong in the public domain. “It was a disaster to begin with,” she says.14But she persisted, piecing together from the available evidence details about Armstrong’s activism, such as how she rejuvenated the city’s Women’s Labour League and challenged men to educate women about labour activities during the general strike. “The film became about my struggle to excavate her story from the rubble of history,” Kelly says on the eve of the strike’s centennial year.15

Although she initially had few images of Armstrong to work with, Kelly says she got in touch with family members who had inherited invaluable records from the strike leader. Included in those records were a number of other photographs of Armstrong that Kelly used, along with dramatizations, to bring her story to life. “Film has the capacity to appeal to a broader audience, it has a reach into popular culture that academic monographs don’t have,” she says when asked about the impact of that documentary.16Eighteen years after she made the film, Kelly says there’s still great interest in the story. The film is now included in many high school classes about the strike, and she says she’s been asked to screen the film at events to mark the 100th anniversary in May. “Seeing it helps ground them in reality,” Kelly says. “Humans are performative beings. We want to see ourselves to understand our humanity.”17

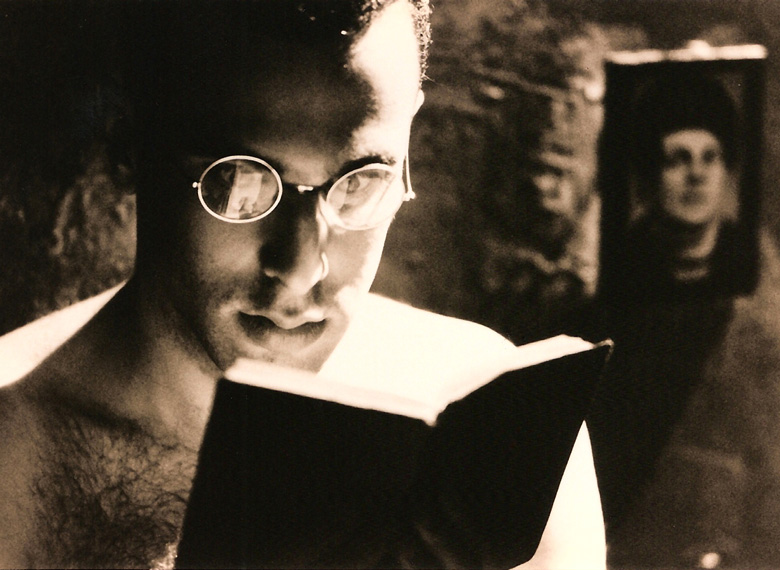

Visualizing those missing pieces is also at the heart of one of the most experimental strike-inspired films. In Noam Gonick’s 1997 short film 1919, the strike is reimagined from the perspective of people who frequent a steam bath just a couple blocks away from where the strike action took place on Winnipeg’s Main Street. The film’s style, in black and white with large captions that flash across the screen, harkens back to the silent film era of the early 20th century. The playful use of water vapour and shadows that shroud the bodies of the men in the steam bath — a nod, perhaps to the absence of queer voices in historical narratives — gives the film a sensual feel.

1919 was the first film made by Gonick, who says he’s always had an interest in the strike, in part because his father was the prominent labour historian, activist, and MLA Cy Gonick. “The Winnipeg General Strike, to me, has always represented the biggest event that ever happened here,” Gonick says. “It’s something that has always reverberated for me, through my existence as a Winnipeg filmmaker and artist. I live downtown, I live around buildings and walk past intersections and streets that were active 100 years ago.”18

The idea of creating a film about the strike as seen through the windows of a steam bath came to Gonick after seeing an exhibit for its 75th anniversary at the Manitoba Museum. At the time, he says he was getting a haircut at a barbershop in Chinatown that also had two steam baths — one in the basement that was “very gay” and one in the back that was “presumably straight.” Gonick says, “This was the oldest steam bath in Winnipeg, so it definitely pre-dated the strike. So I just got to thinking, what was this barbershop and steam bath in this Chinese-run place like 100 years ago during the strike? While that streetcar was going down? While the horses were charging up and down Main Street?”19

Gonick shares a similar approach to storytelling and mythology with Maddin in the way he blends myth and history — in this case blending a queer mythology of Winnipeg with the real events of the general strike. It’s perhaps no surprise then that the next film Gonick made after 1919 was a documentary about Maddin. “We're all just myth makers,” Gonick says. “As somebody who has made normal documentaries too, I know that there's just as much mythology in those.”20

From Arsin to Gonick, Kelly to Schur, the past 100 years of films about the Winnipeg General Strike reveal as much what we don’t know about the strike as they reveal what we do. They pose an important question about telling stories rooted in history: Is it more honest to stick with what we know, or to let our imagination fill in the gaps of the historical record? It’s a question that was posed by Maddin in My Winnipeg, and it’s a question that is even more pertinent as filmmakers attempt to bring in people who have been left out of the frame.

Producer Danny Schur’s Stand! will be released in late 2019. See the trailer here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5JllrjJ_XpQ

Isaac Wurmann is a freelance journalist living and working in Winnipeg. He is a recent graduate of the journalism program at Carleton University, where he completed a double major in journalism and human rights. Isaac has a deep interest in human rights, including labour rights, and the ways storytellers including journalists, writers, filmmakers, and artists interpret these stories. He has written for publications such as Ottawa Magazine, Roads & Kingdoms, and The Reykjavík Grapevine and has experience in documentary making with CBC Radio.