Jeremy Shaw’s Quantification Trilogy (2014-2018) is steeped in science fiction concepts with strong narrative hooks, extremely intriguing backstories, beautiful imagery, stunning use of sound, and incredible dance choreography. Shaw’s trilogy is an experience of transcendence, providing valuable insights into how we grapple with technology, privacy, environmental collapse, and the nature of belief in the contemporary era.

The three short films in Vancouver-born, Berlin-based director Shaw’s Quantification Trilogy, Quickeners (2014), Liminals (2017), and I Can See Forever (2018), look like documentaries dating from the near to far future of the networked human experience where technology overtakes spirituality in the public imagination. Shaw’s choice to frame the films as “documentaries” is a fascinating one in an era of “deepfake” celebrity sex tapes and Fox News doublespeak. The natural tendency for viewers to believe what they are being told by an authoritative voiceover and what they see onscreen is fully taken advantage of. Each film is designed to resemble different eras in film history but with a similar narrative structure. The films rely on narration heavily, and each features a different voiceover artist. The narration, interviews with the film’s subjects, and eventually an attempt to manufacture ecstasy, set the mood. Interestingly, Shaw did not set out to make a trilogy of films. He stated that “Quickeners was a starting point from which the next two were basically reverse-engineered... I used the outline of what had transpired 500 years in the future to speculate on what may have been the start of such an outcome 400 years prior [in Liminals]... and then again with I Can See Forever.”2

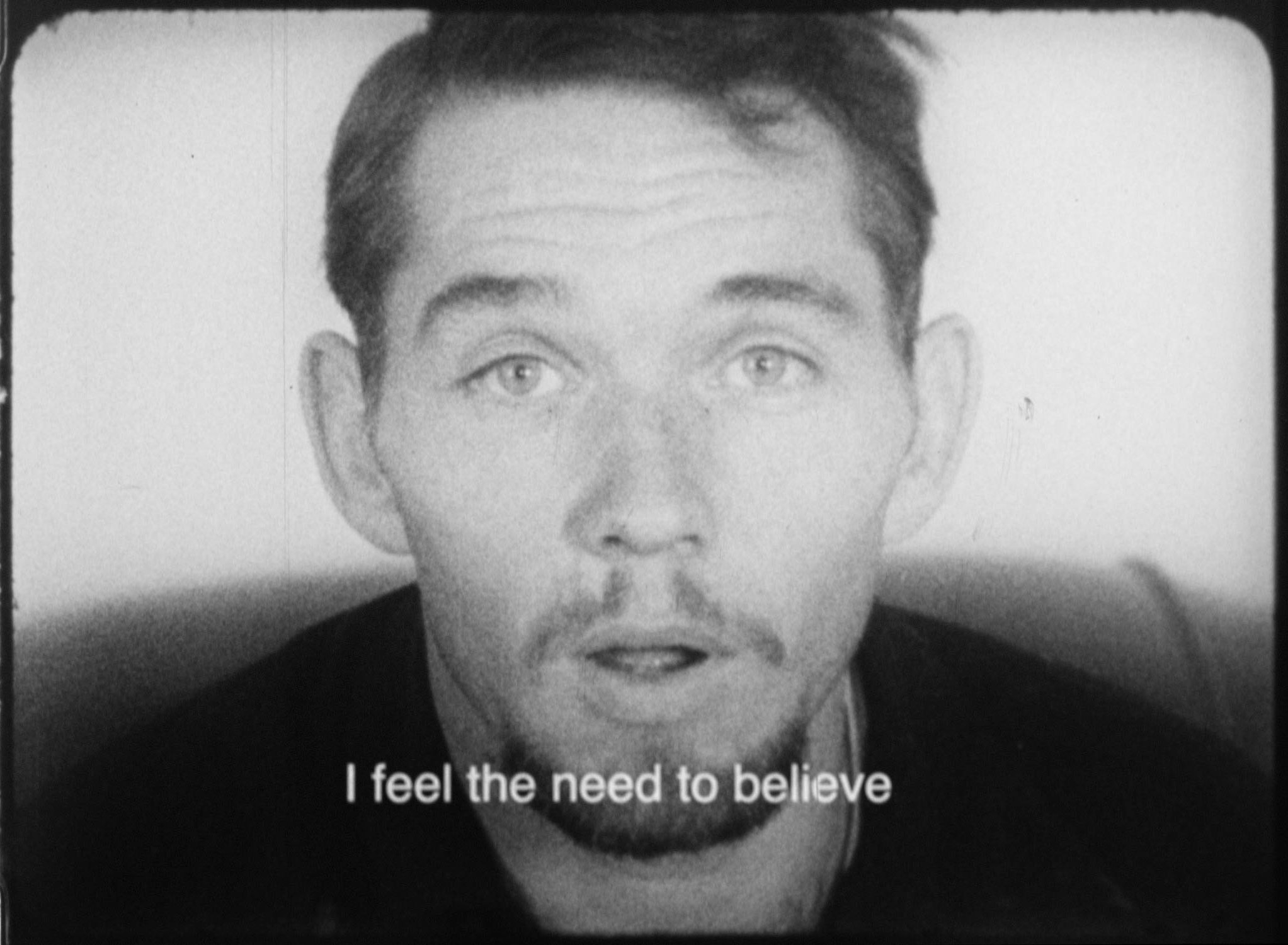

In the opening moments of Quickeners, the camera looks out from the passenger seat of a car at what appears to be a mill town. The narration seems dismissive of the events we are about to witness. Upon arriving at the car’s destination, a series of interviews is conducted with local people who, as a result of contracting something called Human Atavism Syndrome (HAS), have been ejected from the presumably utopic Human Hive. The narrator notes that the Quickeners remain “immortal, quantum humans, like you or I.”3HAS has resurrected some social and mental traits that were believed to have died out long ago along with biological humans, like the desire to believe in a higher power. The Hive is spoken of as being the post-Singularity4state of humanity, where everyone exists in a complex, networked state, and former human pleasures like being able to be alone with your thoughts have been left by the wayside. In such a world, atavism—the return to ancient and ancestral ideas, forms, and biological structures—is seen as the highest heresy imaginable, a regression in the face of technological progress.

The “interviews” and the rest of Quickeners, has been reworked from real-world documentary footage about a snake-handling Evangelical Christian sect from Appalachia in mid-century America. The black and white imagery, with its degraded and grainy texture, is reminiscent of newsreels, or perhaps the early films of Frederick Wiseman such as Titicut Follies.6Following the interviews, a revival meeting is conducted. The end goal for the participants is to induce a “quickening”, an ecstatic state that Shaw depicts onscreen by having the bodies of the lucky ones painted with bright colours. As one participant says, a quickening is “a transcendent state that’s empty of technological content, but full of everything that only exists as information in the Hive.”7

As the film runs repeatedly on a loop, the first thing that draws the viewer’s attention is the disconcerting mix of audio, visuals, and subtitles. The speech in the interviews and revival meeting have been remixed by Shaw into a kind of machine language glossolalia8with subtitles that interpret it for us, a feature shared by all three films. In the world of the film, this bizarre speech pattern might be a symptom of HAS but this is unclear. To those familiar with Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 feature film A Clockwork Orange, it almost sounds like Nadsat, the degraded English-German-Russian hybrid spoken by the aimless punks of the future. However, in Shaw’s film it comes off as the ravings of people plucked from a world where communication has evolved past language.

This odd juxtaposition of images, sound, subtitles, and the pseudo-documentary mode, interrogates how viewers experience truth, and how regardless of the scenario being put on display, the filmmaker is always able to manipulate our senses to achieve their own ends. The world Shaw creates in Quickeners, and expands upon in his other two films, urges viewers to remain skeptical about what they are seeing. Much as the Quickeners are looking for a way out of their mechanized Hive-mind state, Shaw asks the audience to consider whether we are perhaps merging too much with our own machines and technologies. While a trilogy might not have been his initial plan, the next two films continue to add meaning and artistry to this future world.

I first saw Liminals, the second film in the series, at a thematically appropriate venue, the Musée des Beaux Arts in Montreal. The Musée consists of five pavilions, the oldest of which have been there for about a hundred years, but looking inside, you wouldn’t know it. The building has been hollowed out and assimilated from the inside with modern architecture and materials. Much like the human protagonists in Shaw’s trilogy, I left the screening of Liminals quite shaken after two full run-throughs. There was just something about the hopeful nature of the protagonists’ mission in the face of absolute environmental annihilation that touched a chord with me. The film’s heady mix of pre-apocalyptic concerns, encroaching technological advancement, and ironic faux-documentary stylings marked it out as being extremely relevant for today’s viewers.

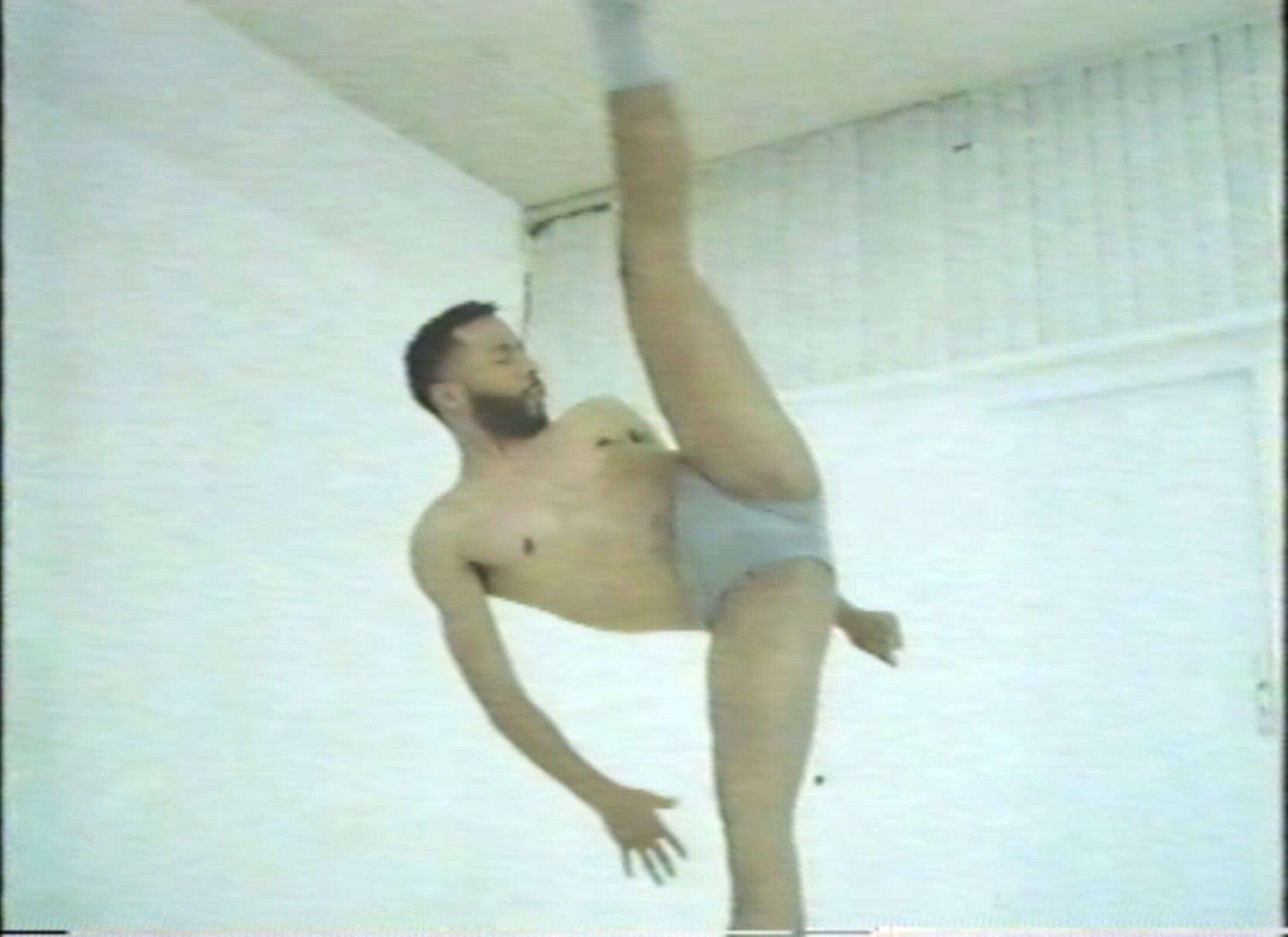

Liminals similarly induces ecstasy and a hypnotic state, this time filmed with a faux documentary style that is reminiscent of direct cinema, The Battle of Algiers, and BBC-produced educational films from the 1970s. Presented as the fourth episode in a documentary series about “periphery altruist cultures”, the film begins with static shots of a featureless dance studio, complete with film jitter reminiscent of early movie technology dating back to the Lumiere Brothers’ first experiments. The narrator tells us that in the near future, some three generations before the expected end of human life on the planet, the aforementioned periphery altruist cultures have begun experimenting with the melding of humans and technology in a desperate attempt to combat the apocalypse. The concept of “Altruist” here is not given the same level of context as Human Atavism Syndrome, as there remains a bit of distance between the narrator and the periphery altruist culture on display.

The film’s heady mix of pre-apocalyptic concerns, encroaching technological advancement, and ironic faux-documentary stylings marked it out as being extremely relevant for today’s viewers.

The Liminals are said to be working towards either entering or outright creating a “paraspace”, a concept gleaned from the works of sci-fi author Samuel Delany, who is mentioned by the narrator.9Unlike the Quickeners, who seek in their ecstasies an escape from the networked world, the Liminals hope to escape the dying real world altogether into a kind of human-machine hybrid dimension. The idea of a machine that attempts to stimulate humanity’s atrophied spiritual core reminds me of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? where VR technology allows people to experience a godlike being’s steps towards ascension through pain and suffering. As the Liminals narrator has explained, humanity’s capacity for spirituality has diminished in the years since experimentation with machine augments began.

We are introduced to the titular Liminals; beings who remain fairly indistinct from each other throughout the film without names, titles, or a hierarchy. At this point in the film, Shaw’s cinematic techniques expand to include hand-held cameras, zooms, and shifting focus. Similarly, brief interviews are conducted with the Liminals, who exhibit the same glossolalic tendencies as the Quickeners, albeit this time with a heightened sense of catastrophe propelling their actions. Shaw notes that the dialogue for both Liminals and Forever were not scripted in order to match the “remixed” aesthetic of Quickeners. He described this process as “I ask questions within certain parameters of what I want the end result to be. This allows me to continue to manipulate in and out of sync with the speech/subtitles.” He added that: “We practiced all the movement as though it were a workshop and then we shot it that way as well. The idea being to try and capture a very authentic feeling documentary environment. As all the actors are dancers, they're very used to this type of thing so it seemed quite natural” which helped with the improvisational feel of the shoot.10

As the narrator in the film explains, the Liminals are using a variety of sensory techniques to attempt entry into paraspace, including breathing exercises, uncontrolled dance, and freezing themselves in place. Furthermore, they employ outside stimuli like disco balls, dream machines, and strobe lights. Amusingly, these techniques and items are described using anthropological language for the intended far-future viewers of the film. The Liminals have a kind of cargo-cult aspect to their behaviors, telling us that their belief in these relics of human civilization hold the key to their species’ next evolution: as one Liminal says it, “was faith that made Humanity evolve, and a new faith will do it again.”11

It is once this group of ontological voyageurs begins to put all of their physical and mental techniques, as well as their antique Human technology into action that the film kicks into high gear, culminating in a sequence that literally took my breath away. The hiss and pop of the faux-documentary soundtrack dissipates and is replaced by a haunting, elegiac score featuring multiple human-led vocal harmonies that circle around a machine drone and synthesizer drums. The disco ball, strobe lights, and dream machine are fired up, and the combination of these effects makes for a film sequence that translates back into a series of still images rather than the persistence of film movement illusion. It is almost as if the movements and bodies of the dancers are being converted into binary code, which makes what happens next all the more exciting.

Up until now the film was projected in a standard full-frame square ratio, but once the paraspace is entered, the screen stretches out to fill the new world. Where the Quickeners’ glimpse at ecstasy is denoted by colouring their shaking bodies on the film, when the Liminals hit their peak, the film itself becomes more “digital”, colourful, and strange. Shaw melds together the still-dancing figures into a collage that is accompanied by the music’s similar breakdown into component noise. The artifacting effect that Shaw relies upon here is difficult to describe, but also something that is inherently understood by all users of online media: a once frozen image—like a dancer shot from the waist up, spinning—suddenly breaks down into pixels, and then a new movement coming from behind wipes those pixels away and incorporates them. After a few minutes of this chaotic, melding, shifting digital landscape, the film ends its rotation with calming music and a bright neon colourscape.

I Can See Forever, the final film in the trilogy, shifts its filmic style into a kind of mid-nineties documentary interview show in the style of Discovery Channel programming. The aesthetic has shifted back into the VHS era, complete with tracking and other analogue degradations. I Can See Forever takes place much closer to our current time, maybe forty years from now, and the mise-en-scene is immediately very impressive. From clothing, apartment furnishings, TV sets, and hairstyling, the film presents an eerily plausible nineties aesthetic for its futuristic story; however, the glimpses of society we get in the film is anything but.

Unique among the unnamed characters in the other films, this film features Roderick Dale as the protagonist. It is unclear whether Dale is the sole survivor or maybe just the sole human survivor of a project that aimed to meld human and Machine DNA, which resulted in AI taking over 700 test subjects. Four children were born over the course of the experiment, and Dale, who only possesses 8.7% Machine DNA, was spared whatever fate befell the others.

Even though he too suffers the glossolalia featured in the first two films, Dale’s malady seems to be much less severe. We are further endeared to him by the narrator/interviewer, who is physically present during the interviews, and appears to understand his speech, although we never see the narrator onscreen. As Dale himself is much more of a character in this film, the narration seems more favourable to his plight than in the previous films. Regardless of his linguistic difficulties, Dale’s true means of communication is dance, a skill he’s picked up by watching routines on TV.

By layering found footage remixed into a far-future religious experience, filming an attempt to foment religiosity itself in a population that has had it burned out of their skulls, and then finally showing us the experience of seeing forever, Shaw speculates about the future of our species.

In a sequence that combines impressive dance acuity with unique choreography, Dale performs wearing only socks and underwear in a blank room not unlike the one used by the Liminals. The actor playing Dale is supernaturally good at dancing, so much so that it’s unclear whether any digital effects have been used in this scene. It is both impressive and somewhat eerie. Similarly, the music for this sequence, which starts off diagetic—part of the world of the film and something the characters could hear—quickly becomes non-diagetic, benefitting the viewers.

This technique demonstrates how Shaw has moved from showing us the means by which people achieve transcendence. He manufactures a kind of ecstasy as a literal escape from doom that actually involves the viewer in the action onscreen allowing us too to “see forever”. When Dale reaches his crescendo, the same “artifacting” digital degradation effect occurs with neon lights highlighting his shifting form. Then, a glowing vector image of an infinitely repeating square appears on screen rushing outward, combined with a beat that strikes every time the square hits the edge of the frame, the edge of perception. This hypnotic effect involves the viewer directly in the experience of “seeing forever”. The effect builds, the square rotates, and changes colour, but eventually recedes back to an image of birds flying above a beach, resetting the film for another viewing loop.

The Quantification Trilogy is an impressive experience. By layering found footage remixed into a far-future religious experience, filming an attempt to foment religiosity itself in a population that has had it burned out of their skulls, and then finally showing us the experience of seeing forever, Shaw speculates about the future of our species. Should we continue to experiment with A.I. and embed technology into every corner of our lives, given how the Singularity Project was perceived at the time by documentarians? Can our increasing exit from real-world issues into echo chambers of our own creation be a salve as well as a recipe for more social isolation? At what point, to paraphrase British science fiction don Arthur C. Clarke, should advanced technology be used as a replacement for magic?13

The often bleak, but also mordantly funny, scenarios Shaw presents in these three films are great thought experiments that I will continue to ponder over for the foreseeable, forever, future.

The Quantification Trilogy was on display at the Esker Foundation in Calgary from January 26 to May 12, 2019.