The killer is in the house.

It's a classic trope that's been around since baby sitters started babysitting, since the earliest days of horror films. The underrated classic, Black Christmas (1974), uses this effective twist but, ingeniously, rather than saving the revelation for the end of the film, director Bob Clark reveals it early on, establishing tension within the first few minutes. From the outset, we know what the doomed sorority does not: a killer has penetrated their place of safety, and is creeping down from the upstairs attic, picking off their sisters one by one, then telephoning from inside the house after each murder.

...yet one after the other, these clueless, ineffectual men are helpless to save anyone.

While the scares increase with each kill, Clark avoids excessive gore and a high body count in favour of Hitchcockian suspense, implied violence, and an overwhelming and prolonged sense of abject female fear. Unlike the generation of slasher films it would inspire, Black Christmas portrays the sorority sisters as real women with vibrant personalities, passion, and humour, rather than merely two-dimensional bait for a killer. Radical for its time, the film even takes a pro-choice stance as our main heroine, Jess, reveals her pregnancy to her boyfriend and refuses to abandon her education and life ambitions in spite of his insistence and desperate pleas. The sisters are surrounded by potential heroes, ranging from hockey-playing boyfriends to concerned fathers and police detectives, yet one after the other, these clueless, ineffectual men are helpless to save anyone. Discussing the slasher genre, Carol J. Clover, writer of Men, Women and Chainsaws, and creator of the ‘Final Girl’ theory, writes “Policemen, fathers, and sheriffs appear only long enough to demonstrate risible incomprehension and incompetence.”1This got me thinking about the short story The Bloody Chamber published by Angela Carter in 1979, a feminist re-telling of the French folktale “Bluebeard”: the story of a nobleman with a habit of murdering his wives. Where the rescuers in the original Bluebeard are the Bride’s brothers, Carter swaps in a wildly powerful matriarchal character. While Black Christmas and The Bloody Chamber are remarkably similar structurally, it is this permeability of gender in their narratives—and in the narratives of many slashers—that make them so successful and demand further exploration. They both create for themselves the ideal space for gender-swapping and lure me into an awareness of my role as a male viewer/reader.

The similarities begin in the depiction of our killers, the psychotic Billy in Black Christmas, and the blood-thirsty Duke in The Bloody Chamber. Before we get any visual details, the Bride introduces her husband, the Duke, through the sound he makes: “I could hear his even, steady breathing…”2Similarly, we don't see Billy at first, as the scene is shot from his point of view, but we do hear the sound of his ‘even, steady breathing’—a soon-to-be slasher trope. Billy is light on his feet, preferring to sneak around in the shadows as he stalks his prey. He is so effective at this that no one—not even the audience—ever sees Billy's face fully revealed. Clark keeps it obscured with shadows, plastic, and doorways throughout the film. The Bloody Chamber’s Duke also likes to sneak around, and would often tell the Bride's servants “not to announce him, then soundlessly open the door and softly creep up behind [her] with his bouquet of flowers...”3 His face is also obscured in a way—the Bride describes her husband as absent even when visible:

And sometimes that face, in stillness when he listened to me playing, with the heavy eyelids folded over eyes that always disturbed me by their absolute absence of light, seemed to me like a mask, as if his real face, the face that truly reflected all the life he had led in the world before he met me, before, even, I was born, as though that face lay underneath this mask. Or else, elsewhere.4

Seeing and not-seeing create horror. Carol J. Clover tells us, “Horror privileges eyes because, more crucially than any other kind of cinema, it is about eyes.”5Coincidentally, each of these stories has a key scene featuring a disembodied eye. These moments occur when both women are driven forward into darkness by their curiosity, and the true horror of their situation is finally revealed. In Black Christmas, after Jess barges into a bedroom and tumbles to the floor, she spies the bloodied bodies of two of her housemates. The sound of breathing leads her eyes up and over to the crack in the door, and out of the darkness gazes the mad, staring eye of Billy himself, commencing my favourite ten seconds in horror movie history. Billy whispers from behind the door, “Agnes, it's me, Billy. Don't tell 'em what we did,” suggesting that Jess herself is somehow complicit in these crimes, perhaps inferring that her plans to terminate her pregnancy make her a murderer as well. The Bride of The Bloody Chamber is also confronted with an accusatory eye, moments after discovering the Duke's former wives on rack, wheel and Maiden. It manifests upon her wedding ring: “The light caught the fire opal on my hand so that it flashed, once, with a baleful light, as if to tell me the eye of God—his eye—was upon me.”6 The Duke later suggests that the curiosity that led her to that horrible place caused her to play a part in her own demise.

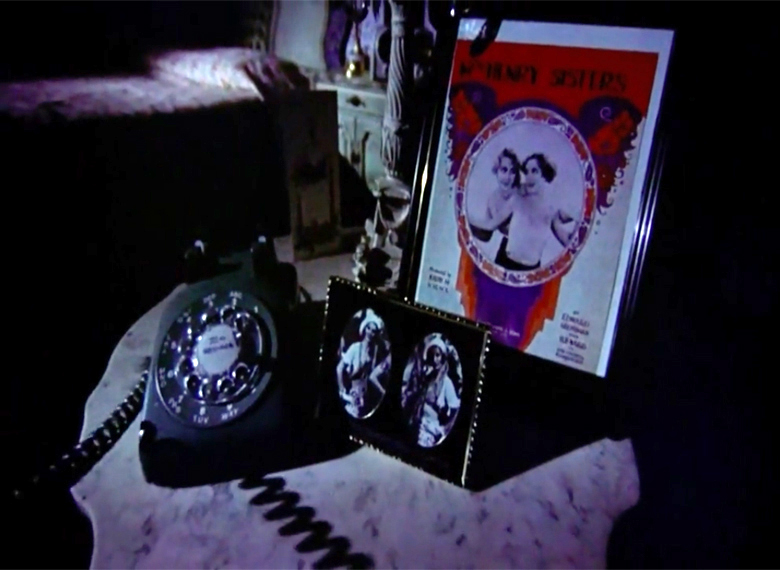

The telephone—a device that reinforces the theme of seeing/not-seeing—is the focus of some of the most terrifying scenes in Black Christmas, turning the killer into a bodiless, transcendent voice, and causing us to jump every time its “insistent shrilling” fills the room. The film teases us into thinking that Jess clubbed and killed Billy, yet as she is put to bed, once again abandoned in the house by her clueless male counterparts, the camera pans back to the attic where the door slowly opens. A minute later, the shrieking telephone cuts through the darkness of the house, proof that Billy has killed again. This idea of the telephone as the harbinger of invisible doom is also perpetuated in The Bloody Chamber when the Duke reveals his murderous intent towards his young Bride then tells her, “Wait in the music room until I telephone you.”7 While she tries to stall in time for rescue, the telephone's “intransigent call” fills the room, creating a soundscape of dread and impending death.

...the shrieking telephone cuts through the darkness of the house, proof that Billy has killed again.

In The Bloody Chamber, the Bride enters her husband's secret lair, revealing his true monstrous self. In Black Christmas, however, Billy's secret lair in the attic is never fully discovered. The final shot of the film is Billy's first victim staring out of the attic window through the veil of dry-cleaning plastic that was used to smother her, as if she's given up hope of ever being found at all. Without his ‘Bloody Chamber’ being discovered, Billy is never truly revealed. And in this final death, that of our heroine, our strong ‘Final Girl,’ Black Christmas defies the very genre expectations it would help to introduce, and leaves us in a dark pit—unlike the grand rescue of Carter's fairy tale.

The Bride in The Bloody Chamber is saved in the nick of time, not by a knight in shining armour, but by her mother, the bold matriarch, a figure so obviously missing from the Black Christmas narrative. Early on in the film, Barb, one of the sorority sisters, receives a call from her mother, informing her that she won't be available for the holidays. Barb is left disappointed, alone, and ill-fated. Even the sorority’s alcoholic housemother abandons them in the midst of their need. But in The Bloody Chamber, as the Bride awaits the fall of her husband's axe, her mother appears in true heroic fashion:

You never saw such a wild thing as my mother, her hat seized by the winds and blown out to sea so that her hair was her white mane... one hand on the reins of the rearing horse while the other clasped my father's service revolver... Now, without a moment's hesitation, she raised my father's gun, took aim and put a single, irreproachable bullet through my husband's head.8

A tear-filled phone call from the Bride had triggered her mother's “maternal telepathy” and sent her dashing off to the castle to rescue her daughter—a tremendous finale in sharp contrast to the bleak fate of the sisters of Pi Kappa Zeta.

But what if Barb’s mother had shown the same maternal telepathy? Would she have burst into the sorority house in spectacular fashion, unveiled Billy's Bloody Chamber and mercilessly dispatched him? We can imagine it, yes, but would this maternal heroism, this reversal of the penetrator, the female embodiment of the masculine, indeed have been a feminist development, or simply “a particularly grotesque expression of wishful thinking,” as Carol J. Clover says. Is the Final Girl “simply an agreed upon fiction, and the male viewer’s use of her as a vehicle for his own sadomasochistic fantasies an act of perhaps timeless dishonesty”?9I'm faced with the reality that in situations similar to those featured in our two stories, I would probably be just as ineffective as the men depicted, adding the fear of my own inadequacies to their unsettling nature. That is undoubtedly what the creators wanted, and perhaps the reason why I have watched and read them so many times, equally terrified and intrigued, and so very thankful that my apartment does not have an attic.