Take a deep breath, fill your lungs with salty, cold air. The water around your chest feels constricting, your body is so cold that it wants to hyperventilate. Exhale again, give your heart the room to pump between two empty lungs. Inhale. Push yourself further and take another step into the water. When you plunge your head underwater: silence. Then, as you adjust to this new air, crackling sounds emerge. You imagine hundreds of unseen small creatures, making snapping sounds that fill your head. Miles away, a cranking sound: motors reverberate so much farther down here, grinding as a cargo ship pulls water underneath it, moving through the thickness of the water. You’ve never heard the songs of whales here. But sometimes you dream those songs up, playing them in your head as you float in salty, cold water. Songs that echo despite the industrialization that desires them to be drowned out.

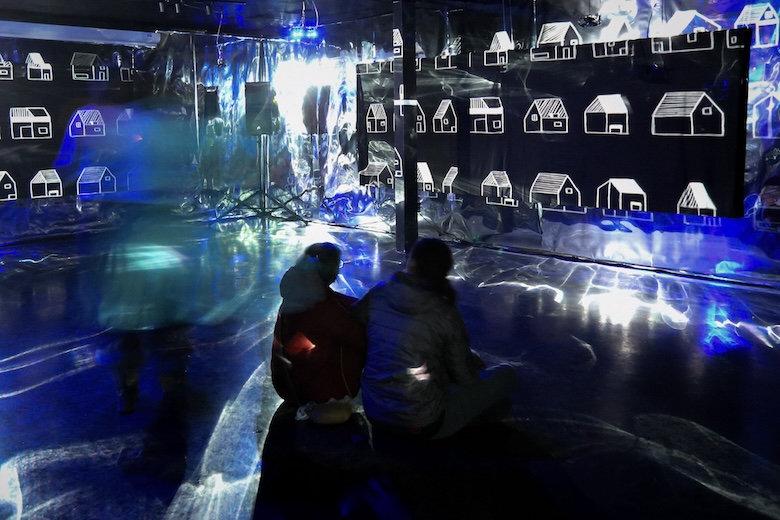

Entering the exhibition Voices by Laura Anzola (January 12 - February 24, 2024 at EMMEDIA Gallery and Production Society) reminds me of plunging into the cold, dark waters of the Pacific. The room is dim, the walls wrapped in reflective material with hand-drawn animations traveling around the space, projecting watery refractions of light. In the darkness, speakers suspended from the ceiling are illuminated with a blue hue as voices spill out from them. The exhibition features the personal narratives of Calgary’s immigrant community gathered by Anzola through a series of interviews. Their stories are an intimate retelling of their experiences with immigration. Anzola’s artistic practice considers mobility, identity, equality, and negotiations of the self through the lens of her experience as a Columbian immigrant. Voices expands on this work, weaving together a multitude of immigrant stories that are at once deeply personal, yet bring forth a collective experience that highlights systemic influences on global movement.

Within the gallery, speakers are placed around the room encouraging movement; each individual voice moves freely between each of the speakers. As a new speaker becomes blue, I travel to the next voice. One immigrant speaks on failing to remember the four quadrants of Calgary, ending up on the other side of the city from where she needed to be. Another describes feeling like a tree, uprooted and placed in new, unfamiliar soil, suffering from root shock. I tilt my head to hear their story, a deep focus comes over me as I parse out the words in this new memory. Sometimes, (honestly, most of the time) when I really want to hear the words, I have to close my eyes to focus on a single voice. Closed eyes, head tilted: deep listening. Listening like when I plunge myself deep into freezing waters to remind myself, that I have a body, remind myself of the aliveness of it all. Voices encourages this exercise in deep listening but also highlights what is lost when we shut out others in the process - when I am too focused on listening to one voice, I cannot hear the others.

Closed eyes, head tilted: deep listening.

One voice describes a memory of crossing one border to another, fleeing a civil war. At the crossing, the voice describes expecting violence again at this threshold, the uncertainty and danger palpable. Across the room, two other speakers are activated, both voices chiming together. Then a fourth speaker is triggered, and a light smattering of laughter tumbles down into the space. The sound rises as all the speakers light up, voices coming together to a crescendo. For a moment, the space is overwhelming, voices rise from all directions and it’s nearly impossible to pick out a single line of speaking. These multiple voices dissolve into ethereal music, and the sound of humpback whales singing gradually emerges. Projected hand-drawn animations of a humpback whale travel around the room; the walls covered in iridescent paper reflect the ghostly light onto the floor, evoking images of light refracting underwater. I can’t help spinning around watching its movement, a small smile at the corners of my mouth.

Humpback whales can weigh up to 40 metric tons. Their heavy bodies travel immense distances through migratory highways called blue corridors. One whale was recorded traveling 18,942 kilometres over 265 days from the polar waters near the Antarctic Peninsula to the southern waters off of Columbia and back.1They are considered an “umbrella species”,2representatives of the complex ecosystems that they travel through; a species that supports their ecosystem throughout the trophic cascade. In a conversation I had with the artist, her face lit up when I asked her about the whales: why were they included in the exhibition? (Why did the section with their singing feel like a respite from the multitude of voices?) Anzola’s inclusion of the humpback whale is two-fold: a deep affection for the animal and a respect for the resilience and breadth of the humpback whale's migration. This adoration is also evident in Anzola’s process of making Voices. Her approach within the project is relational; like the whales that feed entire ecosystems through their movement, Anzola developed an ecosystem of beings coming together to weave this song of voices. In talking with her about her process, she spoke of her experience working remotely with collaborators around the world, workshopping technical issues and arranging meetings around time zones.

Many histories in Voices describe trying to fit in, adjust to their new surroundings, and find acceptance when immigrating to Calgary while also being constantly othered, navigating social, geographic and linguistic barriers, and the depth of emotions evoked from these negotiations. I am reminded of research published in the scientific journal Cell in 2018 which showed that immigrants from non-western countries have a significant loss of gut microbiome diversity within six to nine months after arriving in the United States, replaced with common Western varieties.3The impacts of immigration and colonial violence don’t stop at the borders of the body. As Anzola writes: “I understand borders not only as a geographically and politically defined lines, like those that determine the territory of a country, but also as lines that are everywhere, anywhere, visible and invisible. I have faced borders that are based in language, spaces, culture and tradition.”4

The inclusion of the humpback whale in Voices offers a blurring of human and non-human, encouraging a multi-species perspective on the violence of borders and boundaries. Micro-biomes, plants, fungi, and human are all subject to the harms of colonialism and the difficulties of displacement are tangible on the tongues of the histories present in Voices. When I think of the blue corridors that whales travel through, I think of how their migration is considered natural, while xenophobic comments are spoken everywhere in front of me: the cost of living is increasing because of them, the housing crisis is because of them, earn your keep, we should help our abandoned veterans first. The violence of being othered is brought to the surface in comparison with the humpback whale’s migration and immigrant geographic movement.

I have faced borders that are based in language, spaces, culture and tradition.

I learned that whale songs can travel for thousands of kilometers along horizontal pathways often termed ‘acoustic guides’.5These songs are chanted across oceans, with male humpbacks synchronizing their growls, shrieks and rumbles. Sometimes these songs cross oceans themselves, spreading melodies throughout the Southern Hemisphere.6I like to think of humpback whale songs as a speculative way to reimagine ways of living through movement; surpassing human-designated borders, and blurring the boundaries that harm and isolate. Similarly, Voices creates a song of language, many voices telling individual stories, that hold at its centre an experience that many know: isolation, awkwardness, excitement, anxiety, and colonial violence. I return again to the experience of tilting my head and closing my eyes to listen deeper: listening to the aliveness of it all.