Sometimes magic looks ordinary from the outside.

An unassuming grain silo sits at the path into the Coutts Centre for Western Heritage near Nanton, Alberta. Visitors may be more focused on the gardens, buildings, and wedding tent at the centre and might completely miss the grain silo.

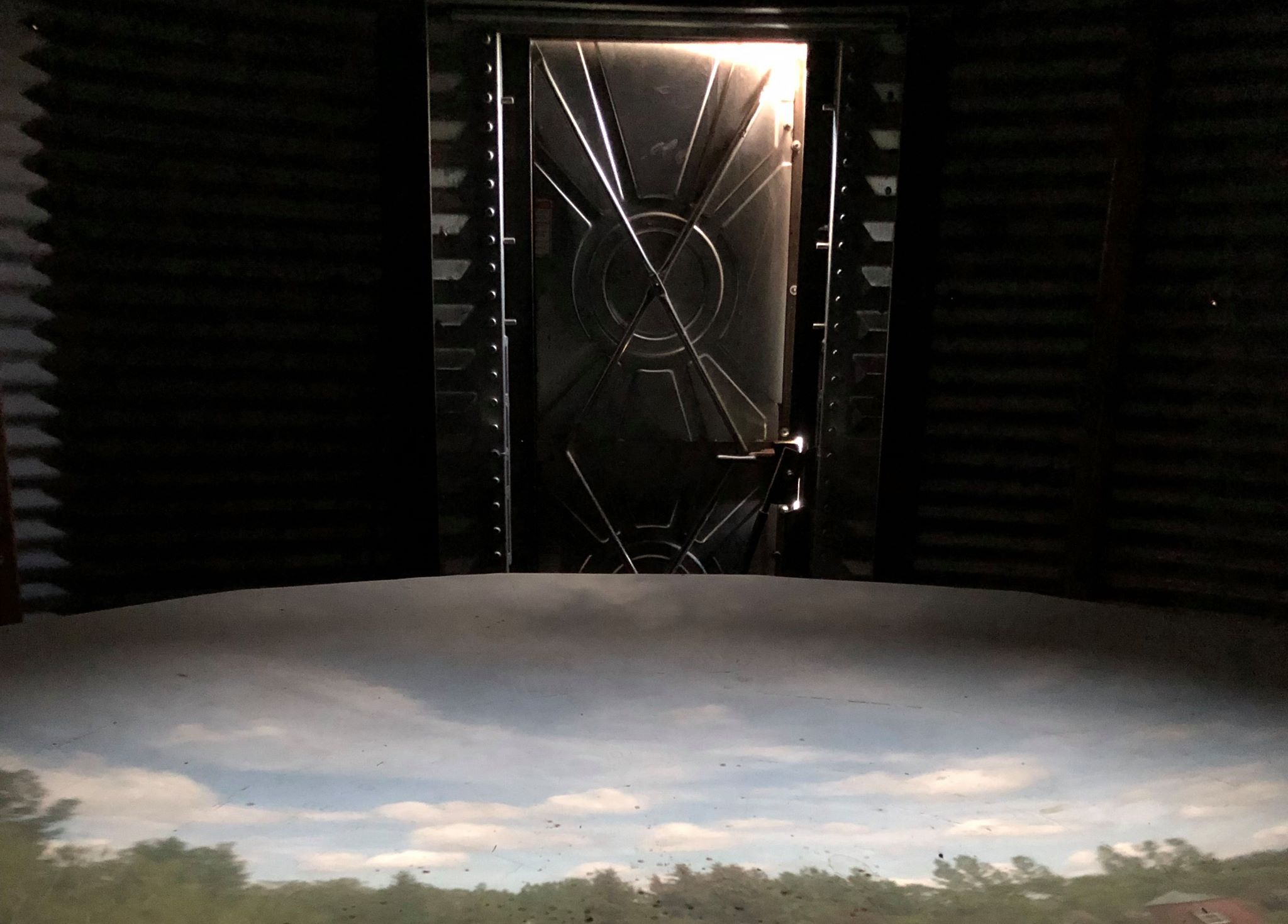

The door is heavy. Working the latch and giving the door a tug creates a loud, metallic squawk. The weight and noise feels prohibitive. How old is this silo? Is this allowed? Should you be entering here?

The interior is dark. A shaft of light is centered in the space illuminating dancing motes of dust and shimmering spider webs. The light pools on a large dished table that fills the majority of the space. The light seems to move and waver like upending the brush water on a wet watercolour painting.

Yanking with all my might causes the door to close with a thunk. A final sound. The room seems even darker. As I turn, the light on the dish has solidified and focused, the Sedge Circle springs to light, an open space surrounded by stones. Humans wander through the frame and silently lie down to listen to Richelle Bear Hat’s multi-channel audio piece Amok-so-ka nik-so-kii-waits (2019) situated here.1The only sound in the grain bin is your breathing, the wind, and the rustling of the nearby elms.

The room smells of dust and the negative ions from the incoming prairie thunderstorm. There is an unknown mustiness to the space. Is that the smell of grain? Perhaps. Or is it the smell of imagined grain? The interior of the silo is definitely a palpable experience.

The space between the wall of the grain bin and the focusing dish is just wide enough for one person to circle. I wander widdershins in this magic dark place mesmerized by the reflected image on the large table in the middle of the small space. Even focused in full dark, the image is soft. It is as if I am witnessing events from a distance, from another dimension, removed, and apart. As I slowly circle the space, my hand reaches into the shaft of light, and casts a shadow on the viewing dish. I ineffectually try to hold a cloud in my hand but I am only a witness. I have no agency here.

I have circumnavigated the grain bin, and now that my eyes have acclimatized, I notice a wheel suspended from the ceiling by a metal shank. I tug on it and it resists me. Using both hands I carefully crank the wheel to the left. The wheel jumps in my hands. A metallic grinding comes from above. The image jumps and refocuses. The wedding tent is in the distance, people wander the Elm Allée to the Writer’s Cottage – all unaware that I am watching from afar. I crank the wheel again the double-decker barn swings into focus. Another crank, the wheel resists turning smoothly and the whole image is now upside down, 180 degrees from where I started. Dark clouds are approaching from the mountains and descending over the prairie. A storm is rolling in over the Coutts Centre.

Crank, more grinding, the light refocuses and I spy upon a group of artists following Edmonton artist Raylene Campbell on a sound walk. They are silent, concentrating on the sounds of their environment, oblivious to being watched. A final crank and I have surveyed 360 degrees around the silo. The silent listeners in the stone circle are frantically picking up blankets and covering speakers as the advancing storm has completely moved in. The elms sway and the leaves bristle violently. The first drops of rain pound upon the roof of the grain bin. The image on the dish has considerably darkened and all the humans have retreated from view. The rain falls in earnest creating a loud, echoing cacophony inside the magic viewer. I am dry inside this metal bin. I watch the rain sheet across the Centre apart and alone.

Typical of the Alberta prairies, just as suddenly the storm has blown in; it blows out. The skies lighten, brightening the image and the sound of the scouring rain on the roof recedes. The elms slow their violent shaking to a gentle sway as the winds follow the moving storm.

Ka-runk!

I am blinded as the magic of the space is broached by light and the heavy door swings open. The viewing dish focused on the space behind the grain bin has neglected to show me the curious media artists approaching from the pathway. I am still, like a deer frozen while crossing a forest road at night.

As I return to the real world, I remember names, responsibilities, and the hour of the day. I mumble greetings and sidle out of the grain bin guiltily having been caught as the unseen watcher. The world comes sharply back into focus as I wander back towards the next session of the conference. Knowingly, I look back. I muse that, perhaps, the new watchers are swept up in the magic and watching me wander away from a distance.2

Created within a 1920s grain bin, Donald Lawrence’s Nanton Camera Obscura is a permanent structure at the Coutts Centre. The grain bin was purchased from a local landowner J.R. Hull. The bin has been situated in the fields of Nanton, Alberta throughout its lifespan and is a perfect example of these prairie all steel structures. Lawrence notes that it is similar in size to the popular magic rooms of earlier centuries.3The heavy door has been added to help block out most of the light. Within the structure is a wheel attached to a shank, attached to a lens and mirror mounted on the roof.

The concave dish that captures the reflected image is constructed of sheets of plywood that have been surfaced with white laminate. The surface is far from smooth but the edges of the plywood seem less noticeable when the viewer is focused on the mirrored image. The artist notes that “There is something peculiar about the quality of light seen in cameras obscura’s projected images, a very atmospheric image that may at the same time be very luminous, clear and soft-focused. The atmospheric quality is sometimes enhanced when there is dust in the air — as has sometimes been the case while working on the Nanton Camera Obscura — and the image’s actual optical structure is seen, projected in conical paths of light from the nodal point of the lens to the outer perimeter of the dish-shaped projection table."4The dish in the grain bin is supported by wood stacked like Lincoln Logs. The grain bin itself is incredibly sturdy and completely capable of withstanding the strong chinook winds prevalent in Nanton.

The siting of Nanton’s Camera Obscura is very deliberate. When asked about its placement, Lawrence responded, “While we looked at a couple of other locations around the perimeter of the homestead the general interest was for the surrounding view to take in “both prairie landscape and human activity.” I do like that the camera obscura can look back to its former home among the other grain bins and have set that as the central focal point of the image.”5While the land and ranch date back to the turn of the twentieth century and the camera obscura itself is a very new addition, there is a synergy of placement. The works presence seems natural and predetermined.

The camera obscura is a magical phenomenon even in this day and age where we can carry the equivalent of a Cray computer in a device that is also a telephone, video camera, still camera, and recreational gaming device amongst other things. While we know more about optics and seeing than ever before, the simplicity and purity of the reflected image still captures the imagination of artists and viewers alike.

Attributed to the 17th century astronomer Johannes Kepler, the term ‘camera obscura’ comes from the latin for ‘dark room’. Before this nomenclature, references to pinhole devices can be found in Chinese texts, early Greek works by Aristotle, and used by the Arab philosopher al-Haytham in the 11th century. European researchers added lenses and mirrors allowing for sharper images that were right-side up. Cameras obscura or magic boxes were frequently used as attractions in resorts and seaside towns in the 1800s. Then the camera obscura fell into obscurity as new technologies of cameras and movie houses came onto the scene. Yet, this seemingly naïve technology still holds relevance and the ability to astound today.6

Lawrence has often used cameras obscura in his work and says that they fulfill two aspects his research practice; an exploration of nature and the landscape and investigation into the historical nature of cameras.7Lawrence regularly plays with sculptural and lenticular, arts-based investigations in his art practice and is the lead researcher of The Camera Obscura Project. This project is primarily based at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, BC and is funded in part by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. The Nanton Camera Obscura is a legacy from the 2015 Midnight Sun Camera Obscura Festival in the Yukon. The festival was conceived by Lawrence, who is a Kamloops-based artist and visual arts professor. Researchers and artists were invited to Dawson City, Yukon to create works on the summer solstice, and harness the unique location and astronomical phenomenon of the north. Among those participating, artists Diane Bos, Lea Bucknell, Ernie Kroeger, Kevin Schmidt, Holly Ward, Mike Yuhasz, , and Andrew Wright.

The camera obscura is a magical phenomenon even in this day and age where we can carry the equivalent of a Cray computer in a device that is also a telephone, video camera, still camera, and recreational gaming device amongst other things. While we know more about optics and seeing than ever before, the simplicity and purity of the reflected image still captures the imagination of artists and viewers alike.

Many of the artists played with the site specificity of Dawson City as well as the enduring summer light. Kevin Schmidt and Holly Ward, Vancouver/Berlin-based artists, created Eye of the Beholder (2015), two cameras obscura that resembled pyrite (fool’s gold) and were large enough for only one viewer to enter at a time. Each camera was focused on gravel but situated in different locations creating a psychic portal between the two structures. Calgary artist Diane Bos played with multiple apertures on the roof of a darkened prospector’s tent to make the night sky visible in daylight. The ephemeral nature became even more pronounced as the projections aligned with a crystal bedecked, star map at the exact moment of the summer solstice.

Lea Bucknell, a Kamloops-based artist, installed a camera obscura in a replica western-style building front titled False Front. Bucknell had also previously created a camera obscura at Wreck City in Calgary. Formerly Yukon-based artist, Mike Yuhasz, built a camera obscura in a rental van and then proceeded to take attendees on tours throughout Dawson City with an inverted projection of the landscape on the interior of the van. Lawrence created a personal camera obscura on the George Black Ferry.

The Midnight Sun Camera Obscura Festival attracted the attention of Dr. Josephine Mills, curator of the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery. Collaborating with Lawrence, Mills brought documentation of the works in the Yukon and even some of the cameras obscura to the uLethbridge Art Gallery in 2016.8The Prairie Sun Project was a concurrent event to the exhibition, held at Coutts Centre for Western Heritage. The Coutts Centre event functioned as a mini-version of the original festival with new responses to the new landscape and light. At this public site event several impermanent cameras obscura were created in addition to Lawrence’s permanent Nanton Camera Obscura.

Together, Mills and Lawrence, have also brought the exhibition to Kamloops and Hamilton. At each stop, a new camera obscura has been created. For the exhibition in Hamilton’s McMaster Museum of Art, Bos created a new multi-aperture work in a steel shed.9This time the holes in the structure were in the configuration of the stars on the artist’s birthday that year: May 23, 2018. Beyond the exhibitions, Mills and Lawrence are also creating a publication documenting all the work and experimentation coming out of this multi-year project.

This on-going research brings the enduring relevancy of the camera obscura to the fore. The Nanton Camera Obscura affects viewers in many ways. Those who interact with it can revel in the childish delight of the reflected image which feels ever so close to magic or they can explore further the deeper meanings of the work. Lawrence notes that camera obscuras “invite a participant to engage in a very tactile, multi-sensory experience that knowingly or unknowingly invokes an earlier, pre-modern mode of image formation for a participant.”10Whether it be the sculptural façade of the exterior that interacts with the environment, the mysteriousness of the darkened room that requires acts of faith and full participation from the viewer, or the frame of the landscape that the artists choose to reflect through the lens – the camera obscura still asks questions and aids in an understanding of our environment and inquiry into our sensory perception.