Unwritten, untheorized and unnoticed. For all that is now made of the relationship between audio-visual artistic production and cultural and political sovereignty in the Canadian Inuit Nanangat, our understanding of the precise origins of that relationship is fuzzy. It is, perhaps, an instance where the ends conceal the means.

For many in the Canadian South, there is Atanarjuat and then there is everything that came before: a pliable history whose key players are Robert Flaherty, the National Film Board and local broadcasting societies. But—and with deference to the above individual, institutions and their work—the variations on this narrative not only tell us little about the issue of origins, they also oddly work to conflate the Canadian North and Inuit Nanangat as uniform space.

Here, I’d like to invert that narrative and look at the introduction and adaptation of audio-visual media arts in a relatively tiny chunk of the Inuit Nanangat—Nunatsiavut—during a relatively brief period—1972 to 1973. The precise duration is, in a sense, mere happenstance. What is vital, rather, is the space. Situated at the eastern edge of the Canadian Inuit Nanangat and within the federally rehearsed borders of Newfoundland and Labrador, Nunatsiavut is itself a construction of layers of legally defined territories (Labrador Inuit Lands, Labrador Inuit Settlement Area, etc.), of resettled and thriving communities (Hebron and Nutak loom as large as Nain or Rigolet) and of religious-cultural traditions (Moravian and non-Moravian alike). And yet, in spite of this web of borders that would conspire to keep it apart, Nunatsiavut remains undivided in its liminality. After Doreen Massey, it remains a product of its interrelations, a sphere of possibility and never, ever, closed.1

On the one hand, the manufacture of such a complex devolved space within Canada seems to be in keeping with the Labrador Inuit tradition. From the point of sustained European contact with the arrival of Moravian missionaries in 1771, the Labrador Inuit have been engaged in social, cultural and political hybridization, processes all well documented by musicologists, art historians, sociologists, political scientists, etc. But on the other hand, the complexity of Nunatsiavut also owes a great deal to the stagnation of those processes of hybridization and the tools used to address that stagnation. Here, media serves in equal parts as catalyst and framework.

Twenty years after Newfoundland and Labrador joined the Canadian Confederation, the limits of hybridization had become fully apparent. Under the new provincial government, Labrador Inuit lost two communities to resettlement, were made to surrender a range of civic rights to the newly minted Northern Labrador Services Division and were subjected to an English language school curriculum devised at and administered from St. John’s. Strategies that had worked within the comparatively isolated Moravian or Hudson Bay Company-administered communities held little sway with new and distantly removed provincial and federal bureaucracies. The former administrations were dependent upon proximity. The latter required something else altogether, something that could facilitate abstracted forms of social and political engagement.

There’s an awful lot that wasn’t put in the film like civil rights and housing…injustices, which for government people is very interesting, to have people tell how they’ve been hassled by the RCMP, etc.

When Ian Strachan began his position of Community Development Worker for Memorial University of Newfoundland Extension Service at Nain in 1972, there were no regional practices of audio-visual media on the North Coast of Labrador save for single-sideband radio. The Labrador Inuit were certainly familiar with all forms of audio-visual media: Captain Donald MacMillan had exhibited films for coastal communities in his boat, the Bowdoin, since the 1940s and early experiments in broadcast radio around the same time at Nain had even hosted performances of Shakespeare in Inuktitut. But, the ability for these to pass into a form of local practice was restricted. Putting aside both the considerable cost of equipment and specialized knowledge required for basic operation at that time, there was limited necessity for such practices in a society that had historically functioned by way of proximity. Predictably, as centralized governments are inclined to do in contexts where such representative practices are absent, its own representative potential would metamorphose into a coercive and destructive force. “Information into Nain was controlled and the information flow back out of Nain was controlled obviously by government and by the hospital,” Strachan asserts. “What we were trying to do was bring in some way that people could feel comfortable with media.”2

In a sense, the de facto mandate of Memorial’s Extension Service was to assist the people of both Newfoundland and Labrador in realizing its new government’s representative potential and had made particular use of audio-visual media in the process. Its most storied endeavour, a joint initiative with the National Film Board’s Challenge for Change/Société nouvelle project, would see the creation of over two dozen short films about life on Fogo Island via a process of participatory, community-based filmmaking. The evident success of the Fogo Process in animating community discussion and organization solidified the role of audio-visual media in the Extension Service’s operations, not merely as media to be produced, but also as media to be received. What its employees came to practice was a fluctuating model of representational production and reception. For Strachan, that model began, innocuously enough, with Big Bird. “We figured that Sesame Street was the least harmful and easily understood in all languages, even if you didn’t understand what they were saying. And beside the VCR we put a camera and recording equipment up.” The addition would prove vital. “People would come in and sit down and watch it and then I added onto that some wildlife things […] and they then started to play with the cameras and we had some blank tapes and we would record what they said and stories from some of the older people and then play them back with the idea of making them comfortable: that if they had no communicating system with the outside world then at least they could start communicating with themselves.”3 This would represent the first instance of local audio-visual production for local audiences on the North Coast.

Today, the vast majority of these early productions are lost, but we have some sense of their devised work by way of living memory. One piece, which continues to figure in the memory of elders, is The Burial of Mousie Dicker, a short film about the burial of the eponymous mouse that came to Nain by way of a Newfoundland fishing boat. Innocuous as it might seem, there is a clear allegorical function in the burial of a rodent from vessels that historically deposited all manner of things—both animate and inanimate—along the North Coast for the Labrador Inuit to deal with. From these pieces, Strachan suggests, it was a small step to begin to film public discourse such as town council meetings that had traditionally been private. As per the Fogo Process, self-recognition would prove the first step towards empowerment.

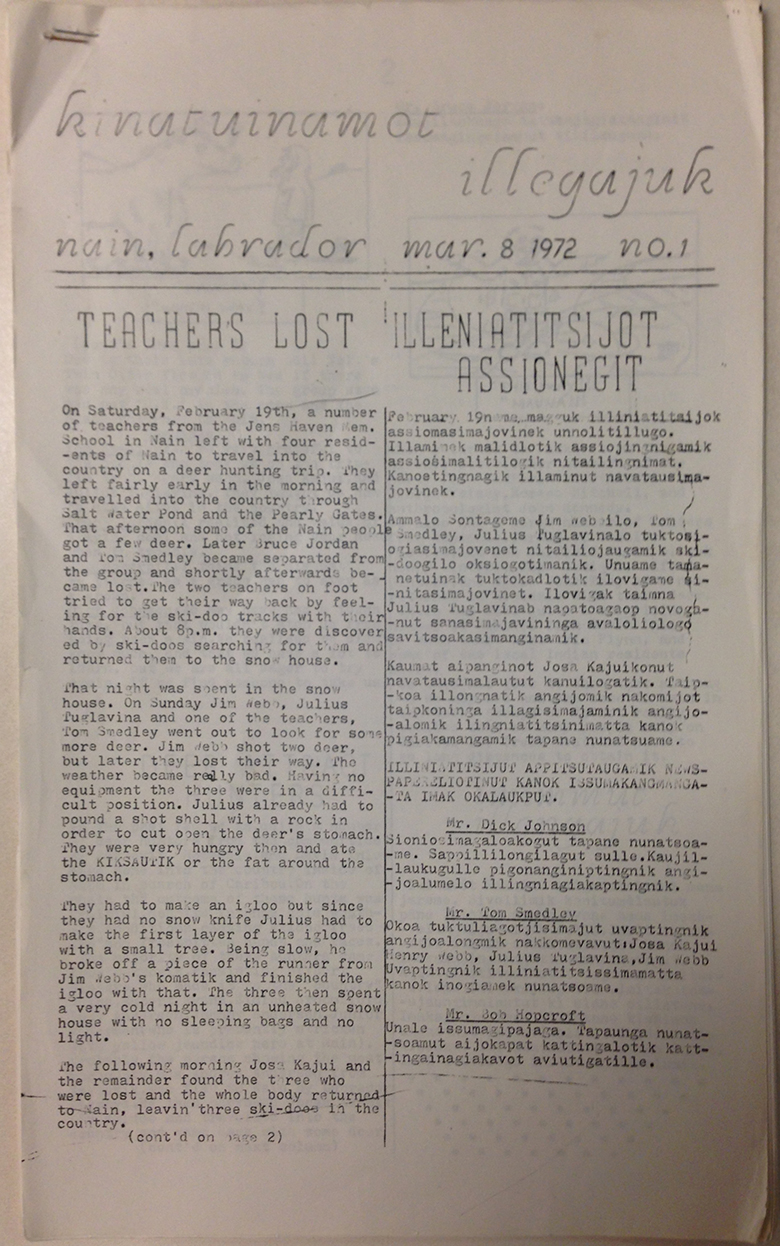

Here, though, there was an essential divergence. Unlike other applications of the Fogo Process which, as Janine Marchessault has argued, resulted in a “conflation of new communication technologies with democratic participation,”4 the Labrador Inuit would veer towards a decidedly luddite technology with a singularly democratic effect. Launched months after the first experiments in local audio-visual communication, the newspaper kinatuinamot illengajuk (in English: “to whom it may concern” or “something for everyone”) would be the first iteration of print media by and for Labrador Inuit. Arising out of a practice of audio-visual discourse, one that encouraged self-recognition and empowerment, and without textual precedent, ki was completely unencumbered by discursive convention at the outset. The value of such a site of public discourse became immediately apparent. The year of its launch, ki broke a story about the provincial government’s attempt to conceal the fact that it had not delivered heating oil to Nain. The chronicle of the government’s lie would only catalyse political will. “People were empowered because people were reading it,” Strachan contends. “People knew the truth; they saw the truth. And here was their paper telling them the truth. It was their paper telling them the truth. And when the government had to back down, that was it.”5

What “it” was was a revolution. Emboldened by the success of their local media practices, the Labrador Inuit put this new acumen to work to widely circulate the narrative of their immediate social and political circumstances, both in provincial and national contexts. Acting as broker, Strachan would facilitate two productions about social conditions on the North Coast. The first, a 1973 episode of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s Land & Sea titled “People of the Torngats” was the first province-wide broadcast of any representation of life in Northern Labrador. Produced by Dave Quinton, the episode emphasizes the contradictory and at times destructive nature of government services in the region while glorifying the apparent anachronisms of local industry such as the char fishery. Though meandering at times, it is apparent that the episode is building upon the concerns of kinatuinamot illengajuk, even if the paper remains un-credited.

More direct is Roger Hart’s 1973 film Labrador North, produced as part of the National Film Board’s Challenge for Change/Société nouvelle project. Hart’s film was originally supposed to chronicle the work of the provincial government’s Royal Commission on Labrador, which was ostensibly established to examine the state of social, political and infrastructural conditions in the region. But reticence on the part of the Commissioners towards the creation of such a document led Hart to restrict his focus to the North Coast where, with assistance from Strachan, he came to document the early stages of the revolution. Though just thirty-seven minutes in length, the film chronicles the process of social and political organization in the three northernmost communities—Nain, Hopedale and Makkovik—analysing the often-contradictory work of government, the Moravian Church and the local response to these institutions. In a debriefing with the NFB after the film’s release, Hart would suggest that what was included was only a fraction of relevant content. “There’s an awful lot that wasn’t put in the film like civil rights and housing…injustices, which for government people is very interesting, to have people tell how they’ve been hassled by the RCMP, etc.”6

In keeping with NFB practice after Fogo, people on the North Coast were given the opportunity to exclude anything from the film they wished. A vital part of the Fogo Proces was editorial agency: without the right to exclude material from the final product, there could be no trust. But, Hart continues, “they cut nothing out. When the film came back really what was put to them was “is this what you want government to see?”7 The answer, obviously, was yes. The response from government was telling. In a letter to Hart, Walter Wason records this reaction to a screening held on 23 January 1974:

On Wednesday morning I conducted a screening before 13 senior provincial government officials from the Department of Education and the Dept. of Labrador Services (with the latter greatly predominating.) They were unilaterally hostile, picky, critical, cranky, incensed and bitchy in varying degrees. (The 14th member of the group was a crippled old Eskimo from Nain who watched with attention and was wheeled away without a word). All the rest remained when I invited them to stay behind for a few moments and give me their reactions, at your special request. A few moments indeed! An hour and twenty minutes later they were still at it, dismissing the film as narrow, one-sided, biased, predictable, unfair, distorted and a waste of the tax-payers’ money.8

A rather severe reaction to what Wason himself suggests is “by no means a classical advocacy film” and “more innocuous, certainly, than the Extension people maintain they would have done.”9

What Wason and perhaps even Hart did not fully appreciate was the degree to which the film—like “The People of the Torngats”—was in a manner authored by the Labrador Inuit to serve a specific discursive function: as both a representation of their nascent political society and a statement about that society’s ability to obviate distantly removed and centralized power. While the notion of local authorship was hardwired into the Challenge for Change/Société nouvelle project, the products of that authorship tended to be relegated to restricted domains. “Discourses of access and participation often work to conceal the institutional conditions of access and the political limits of coming to voice,” Janine Marchessault reminds us.10 But here we are presented with something different: a revolutionary form of authorship that transcends the political limits of coming to voice in a manner that is, at once, forceful, peaceful and acutely aware of the systems in which it operates. I cannot help but think of the elderly Inuk as Wason’s screening for the thirteen government officials.

Labrador North, directed by Roger Hart (1973: Labrador). Film.

VIDEO: Labrador North © 1973 National Film Board of Canada. All rights reserved.

This representational practice, which had begun with public screenings of Sesame Street, brought kinatuinamot illengajuk into existence and enabled the indirect authorship of two films, would find its ends in the establishment of the Labrador Inuit Association in 1973: the body that would negotiate the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement and push for the creation of Nunatsiavut. Though a process-oriented organization itself—the LIA could only exist in the absence of a finalized land claims agreement—as an organization, it represented a codification of representational practice in a national political sphere. Its existence would likewise necessitate that audio-visual practice by its members would conform to certain aesthetic-political conventions. Access to federal funding for production would require it.

Only now, ten years after the creation of Nunatsiavut, and with some sense of the legal and material reckonings of it as space, does the view of those audio-visual practices that led to its creation become clear. They are, I should think, processes that would have particular relevance for any understanding of representational practice in Nunatsiavut’s antipodes in the Canadian Inuit Nanangat—the Inuvialuit Settlement Region—itself codified space within codified space within codified space.