Large curtain-like textiles, hand painted in muted watercolours, fall from the ceiling of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery (SAAG). They move subtly with the air conditioning, cranked on a 34 degree summers day. Derek Liddington’s solo exhibition, the tower will always break before it bends, the body will always bend before it breaks, takes its departure from the Ballet Russes, animating and complicating the gaps between moving image, object, and performance. Balletic silk curtains, wall paintings, video, and hard-angled stone sculpture exchange voices to ask: which is body and which is object?

they danced with the understanding that this was for them, eventually it was, a 32-minute video, plays on loop at the back of the space: a collage of vaguely figurative but ultimately abstract images and lines pasted over footage of dancers practicing in a rehearsal space. Dancers of diverse age and ethnicity enact what looks to be Contact Improvisation, a form of dance developed in the 1970s by Steve Paxton: a kind of ongoing, intuitive movement between partners that eschews choreographic structure. They balance, pile, and pull at each other’s hands and legs with intensity, while I stand on the carpeted viewing area watching the video of the rehearsal progress. Eventually I sit on the ground, feeling very much like a sweaty, sidelined dancer ready and waiting to tag into the formation.

Contemporary art has recently been preoccupied with the idea of rehearsal. Perhaps it is the appealing notion of continuous practice, the unglamorous ‘every day work’ as choreographer Yvonne Rainer calls it: the anti-spectacle of the craft and labour of dance, the earnest physical reality of the body working. In contemporary dance history, the appropriation of rehearsal time into the performative space has a long trajectory. Merce Cunningham’s 1968 computer-inspired Walkaround Time—choreography that still possesses the dubious distinction of drawing jeers nearly half a century after its premiere—features the entire ensemble taking a break on stage, as if waiting between classes or keeping warm during intermission. Dancers stretch, chat, mark a few steps, and sit on the ground cross-legged. Backstage becomes center stage—a mixing of art and life that was top of mind across creative disciplines at that time. This engagement with everyday movement extends through all 48 minutes of the piece’s pointedly un-spectacular choreography, and seems oddly as radical now as it might have in 1968.

Another example of dance documented on film, Walkaround Time was filmed on 16 mm in two parts over a span of four years, and in two locations: 1969 in California using one hand-held camera—like Liddington does for some sequences—and 1972 in Paris using three cameras, meant for a two-screen projection. Charles Atlas’s first 16mm film, years before he was to become Cunningham’s company filmmaker-in-residence, Walkaround Time turned the self-taught filmmaker into a media-dance pioneer.1 Although Atlas believes it is impossible to truly re-stage a performance, the choreography has since opened at Palais Garnier this year. In a 2011 interview with Frieze, Atlas said:

I know that they don’t perform them the way that the original was, and there are certain things that were vital, and addressed issues that were relevant at the time in terms of style of performing. There are just ineffable things that performers do when it’s created on them, and they’re the first expressers of it, that are often not transferrable.2

Nonetheless, I got to see the booing first-hand from a plush little seat in Paris.

It was clear from the beginning that these objects sharing the stage with the dancers in Walkaround Time were performers of equal status. The curtains opened, there was a long moment of stillness and silence, dancers frozen, inflatable props moving ever so slightly, buoyantly with the air circulating through the theatre. Dancers began to move laterally across the bare stage before a minimal backlit scrim, wearing modestly cut leotards and tights in a range of 1970s appliance shades. Walking at different rates of speed and variation in steps, they excised and paused with quiet technical mastery, their movements balletic and razor sharp. Sharing space and time with performative objects, the bodies themselves were made performative objects. Amidst the dizzying layers of quotidian movement, a reversal happened: the prop animated the body, rather than the body animating the prop. As they moved, the dancers entered and exited the foreground, occasionally obscured by the props: large rectangular sculptures made by Jasper Johns in homage to Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass. The readymade possessed the dancer’s body as the deconstructed choreographic elements layered over each other across the duration of the work. It became apparent that running, walking, kicking, stretching, chatting, were in themselves a type of readymade; these everyday activities forever altered by their context on the proscenium stage.

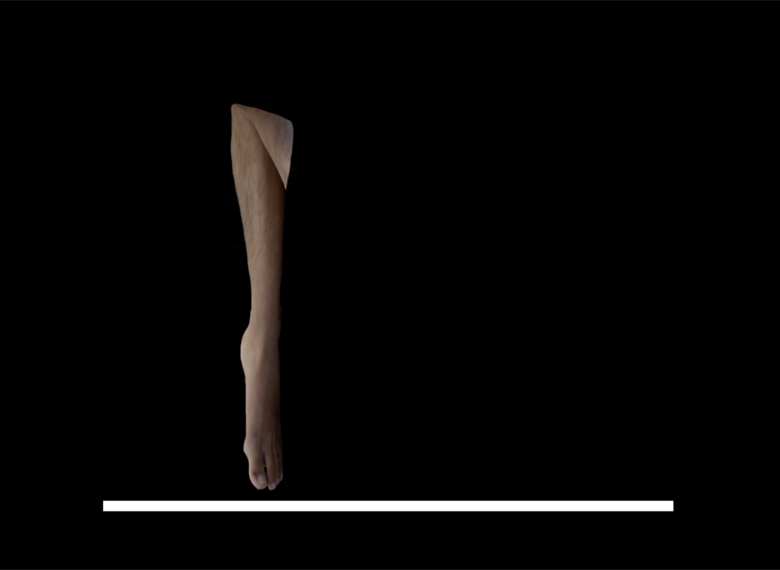

Liddington’s they danced with the understanding that this was for them, eventually it was at the SAAG situates itself within this tradition of quotidian performance on film, movement as readymade. The quality of his rehearsal footage is appropriately distanced and observational, documentary. However, as you ease into the video, the footage pauses and a dancer’s body part is suddenly isolated. A partially extended leg with a slightly sickled foot moves about the frame autonomously, while the rehearsal continues on underneath. Through this animation, as the isolated part bounces and rotates across the screen—a leg or arm or torso—it is reduced simply to a shape. Removed from the image as a whole, the body part starts to read as an object—relating more closely to the angular cast concrete sculptures sitting heavy on the floor throughout gallery, than a moving body.

Established by Sergei Diaghilev in Paris in the early 20th Century, the Ballet Russe—as with Cunningham—had a pioneering relationship with the visual artists of its era; Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Gorgio di Chirico, and Salvador Dalí were some of those who designed set pieces and costumes for the ballet, often at the nascent stages in their careers. Working in the muted jewel tones the Ballet Russes is known for, these artists designed props and costumes that performed and continue to perform in collections and performance documentation. Liddington’s own empirically beautiful silk textiles, painted in the Ballet Russes palette, hang floor to ceiling in panels, functioning both as abstract paintings and symbols of theatricality. Large-scale watercolour drawings also sweep over the gallery walls in the same palette, an overall composition of many small brushstrokes marking the passage of time. The marks read as a trace of the body, an index of the labour involved in its making. The immersive scale engulfs the body whole, while references and highlighting the action of the hand. Even in this, the body of the viewer becomes quotidian, while the objects, textiles, and drawings become increasingly performative—action rather than prop.

Video, photography, sculpture, and painting share a common space and duration in Liddington’s exhibition; autonomous objects from different disciplines have the opportunity to exchange meaning. In this, Merce Cunningham’s notion of ‘common time’ can be detected: a strict collaborative process intended to allow props and dancers to not only co-exist, but exchange and share roles while performing onstage. Various modalities are developed separately but performed in concert together; in the case of Walkaround Time, Cunningham didn’t see the Duchamp/Johns inflatable props until dress rehearsal for this purpose.

Perhaps the objects in shared time and space—the curtains and sculptures in Liddington’s exhibition—actually leech the performative power and energy of the body—dancer or viewer. Both the performer and the prop are alive in performance, but only the performative byproducts will endure, despite their deep inadequacy. The props from Walkaround Time and the Ballet Russe have outlived Cunningham, Duchamp, Dalí, and Picasso, and will persist long after the memory of the choreography or performer. Liddington’s video collage of these dancers will live on, irrevocably intertwining body and abstract shape as a piece of media art history. Atlas’s footage of Walkaround Time has already eclipsed what once was a socio-politically relevant live performance. The body will ultimately fall away, ephemeral and unreliable, but will continue to haunt the objects, props, and data that surround it—a powerful and persistent trace.

the tower will always break before it bends, the body will always bend before it breaks by Derek Liddington will continue at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery (SAAG) until September 10th, 2017.