Since my childhood, Calgary has seemed to infinitely sprawl outwards into the surrounding plains like some sort of science fiction monster, leaving in its wake labyrinthine streets with confusing names and characterless, fake-looking dwellings. This is, of course, the bias of someone raised in the city’s core in a house built in the early 1900s; some treat Calgary’s suburbs as a model of sensible expansion. But isn’t that just the paradox of suburbia: it is chaotic and orderly, familiar and strange, banal and sinister all at once?

While Calgary’s official brand splits the difference between anachronistic fantasies of rural simplicity and the skyscraper-strewn capitalist mecca, the reality is that suburbia vastly outstrips them both. It’s perhaps no surprise that there is a substantial body of academic literature on Calgary and suburbia.1For the same reason, Calgary is a suitable venue for what Bernice M. Murphy calls “the Suburban Gothic,”: “a sub-genre concerned, first and foremost, with playing upon the lingering suspicion that even the most ordinary-looking neighbourhood, or house, or family, has something to hide, and that no matter how calm and settled a place looks, it is only ever a moment away from dramatic (and generally sinister) incident.”2Calgary gets the treatment it deserves in the lean and darkly funny 2019 film Red Letter Day, a grisly treatment of suburbia with nary a cowboy hat in sight.

Red Letter Day is Cameron Macgowan's first feature after directing six shorts. He is also a lead programmer for the Calgary Underground Film Festival. Macgowan grew up in a Calgary suburb3and the film benefits from a strong sense of place, depicting a suburb that feels specific in its generic-ness. The film is set in a new suburb named “Aspen Ridge,” fictional yet suggestive of names of real Calgary suburbs like “Aspen Woods” and “Maple Ridge”.

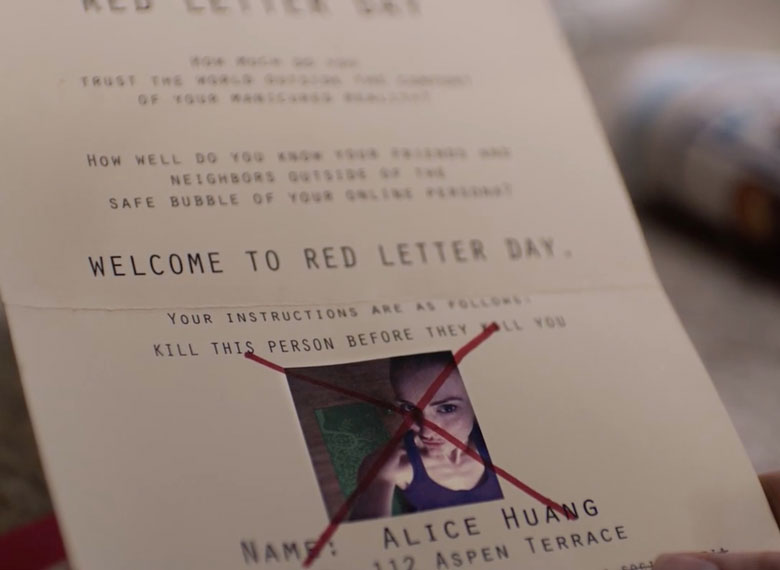

We are introduced to divorcee Melanie (Dawn Van de Schoot) and her two teenage children Madison (Hailey Foss) and Timothy (Kaeleb Zain Gartner), newly moved into Aspen Ridge and only starting to adjust to their new status as suburbanites. They take note of the banal constructedness of their environment but Melanie is determined to make it cool; meanwhile, Madison is dating Luther (Roger LeBlanc), an older schlub and metalhead, though Melanie feels she lacks the moral authority to intervene, having a history of gravitating towards bad boys herself (and having married one). Soon the family receives a set of the titular letters, arriving in red envelopes. Each contains a photo with red ink crossing it out, and an order to kill someone else in their neighbourhood. And here is the twist: everyone who is marked for death has also received the same instruction. It’s an intriguing premise reminiscent of game theory, since the optimal scenario is that neither person carries out the order… but each may feel compelled to act it out in case the other does so first. Or it may unleash a homicidal mania that was always there but needed this occasion to license it.

Each of the three family members react to their letters differently, with different levels of concern, disgust and fascination. Madison tears it up unread. Timothy begins spying on his target, who soon seizes the initiative and comes to the house determined to kill him. Melanie goes to speak to her target, who happens to be her friend and neighbor Alice (Arielle Rombough). All three approaches herald coming disaster.

In wresting the Gothic away from medieval crypts and castles and anchoring it in the everyday (and frequently – as in Red Letter Day – the daylight), the Suburban Gothic offers a set of dark correctives to the Suburban Dream. A key feature of that dream, which Red Letter Day plays on, is that suburbia represents “a place in which to make a fresh start.”4Suburbia promises what the frontier once did for settlers of the New World: a newness, innocence and renewal. All of these effacing the destruction of the landscape built into the construction of suburbs, and the Suburban Gothic works to disrupt those promises by showing suburbia as fraught with danger, paranoia, and violence.

Early in Red Letter Day, we see a commercial for a development company called Harrison Homes (a parody of Calgary’s Morrison Homes, one assumes), using slick, familiar images to promote the kind of safely bland, middle-class lifestyle of the Suburban Dream. But the dark mirror of the Suburban Nightmare instead delivers “a place haunted by the familial and communal past” – in this case, dark secrets motivating mistrust and accusations that inevitably turn to violence. Red Letter Day shows this through Melanie’s interaction with Alice and her husband Lewis (Michael Tan), where the veneer of civility slowly peels back (Melanie openly resents Alice for voting Conservative, and Lewis sees Alice’s status as a divorced single mother as a reason to distrust her). The atmosphere of growing tension worsens when a kitchen knife is found in Melanie’s purse, unwisely stashed there by Timothy but ultimately producing violence instead of protecting against it. The ad for Harrison Homes promises “We Build Community” but as we see, it merely installs the bare trappings of community while encouraging isolation, insularity, and suspicion.

Suburbia promises what the frontier once did for settlers of the New World: a newness, innocence and renewal. All of these effacing the destruction of the landscape built into the construction of suburbs, and the Suburban Gothic works to disrupt those promises by showing suburbia as fraught with danger, paranoia, and violence.

Murphy notes that basements are key locations in Suburban Gothic narratives,5dark spaces cloistered away from the apparent transparency of suburbia’s sunny streets, and it is perhaps no surprise that Red Letter Day’s climax plays out in one. The thinly-explained force behind the Red Letters is a shadowy group called “The Unknown” that, reminiscent of the hacktivist group Anonymous, preaches revolution from behind webcams while wearing creepy masks. Its local representative, inevitably, is the bad boyfriend Luther, who kidnaps Madison to his parents' basement and plans to murder her in front of an online audience of millions. Melanie tracks her there and brutally maims him, while angrily chastising his audience for their voyeurism.

There is a thread in Red Letter Day that critiques surveillance culture and violence in media, but it seems less effective to me than its commentary on Calgary and suburbanization. A fleeting but significant image early in the film is of a soiled diaper vanishing into a Diaper Genie, moved safely out of eye (and nose) but still there. Furthering the fecal metaphor, after watching a viral video of an Arabic man being subjected to a xenophobic rant, teenager Timothy says, “I knew this was the kind of shit that was hidden beneath the surface. I just figured most of it was in the U.S.” The more cynical Madison replies, “Rednecks like this are just always looking for an excuse” – othering the aggressor by hanging a label on him – before broadening her point with, “People are shit.” Tim asserts that there are good people and that “We’re good people.” This line has an echo at the end of the film, when Melanie, looking back on the bloody trail the family has left behind them, states, “We may have done some bad things today, but we are not bad people.” The sentiment resonates with suburbia’s impossible promise of innocence, and Melanie sounds only half-convinced herself by her own assertion.

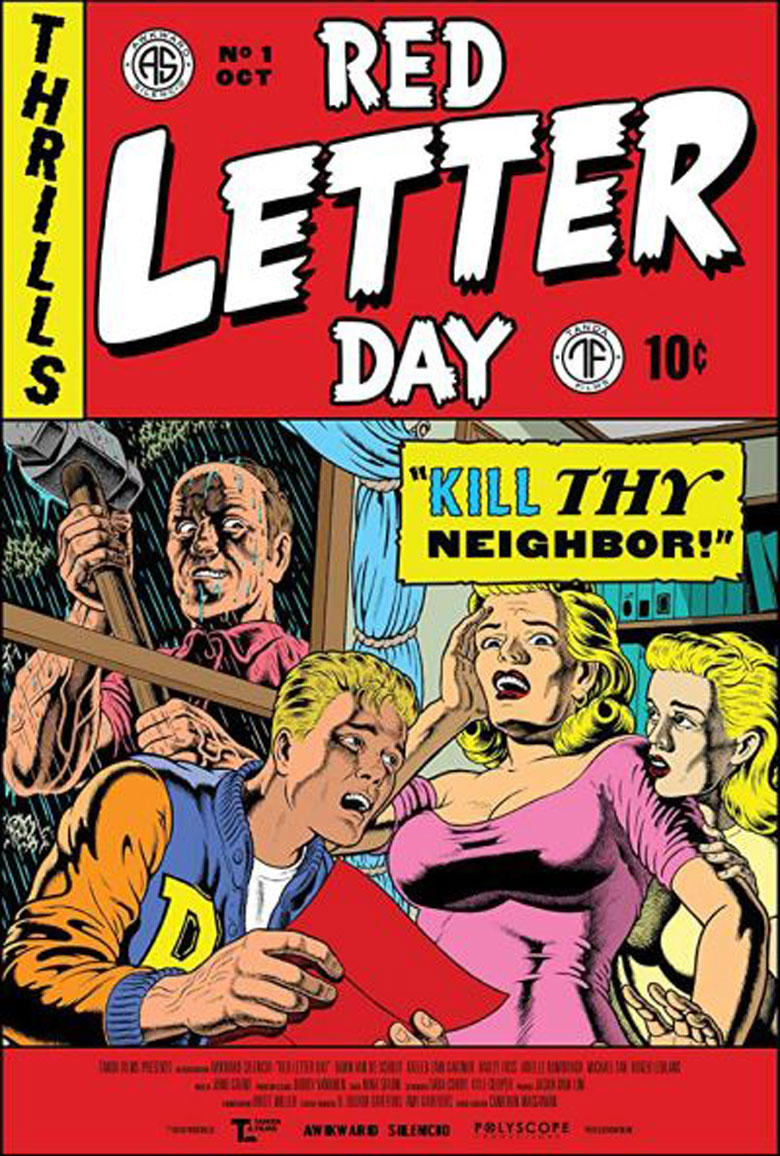

Red Letter Day has plenty of echoes of other films, ranging from The Purge franchise (2013-ongoing) that represents a special “day” that encourages violence, to Calgary filmmaker Gary Burns’s mockumentary about suburbanization, Radiant City (2006).6Red Letter Day’s poster is modelled on a classic ‘50s horror comic and it has some of that nasty, grimly comedic sensibility, featuring amusing touches like Melanie stabbing Lewis with a butcher knife with a full chicken still attached to it. Red Letter Day also has many echoes of the classic Twilight Zone episode “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street” (1960), in which aliens, planning to swoop in and take over once the human race liquidates itself, only need to make small gestures to transform neighbours into bitter and violent enemies. That society at its putatively most calm and orderly is actually a powder keg that ignites at the smallest spark is as trenchant a message today as it was in the wake of McCarthyism.

I found myself appreciating Red Letter Day’s specificity in regards to its Calgary setting, rather than taking place in the generic North American setting of so many Canadian genre films. For example, we even hear of a killing at the Bass Pro Shop in CrossIron Mills, eerily anticipating something which actually happened in Sept. 2019. It seems unlikely anyone will stitch together a Calgary equivalent of Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003)7any time soon, but if they do, Red Letter Day is apt to figure prominently. Timothy’s line about how it seems more likely this sort of thing would happen in the United States would also suggest it is more likely that this story would be set south of the border – even if produced by Canadians. But keeping this bloody product homegrown works to assert that we are not above this, that Canada in general and Calgary in particular are not charmed, Utopian spaces free of discord and violence.

Phil What, a reviewer of the Red Letter Day for a U.K. website writes, “[W]hat actually provides the biggest laugh of this film is the idea that this is happening in Canada. Canada, the politest place on the planet . . . the very idea that Canadians of all people, given the license to kill that the red letters afford them, would gleefully massacre their neighbours is easily the most wonderful aspect of Macgowan’s film.”8At a minimum this reminds us of how unseriously Canada is often taken in the rest of the world. However, I don’t see Red Letter Day’s Calgary setting as a mere joke. Rather it is vital to the film’s key theme: just how feeble, and how untenable, our cherished sense of innocence, with shades of “It can’t happen here”, is becoming.

Red Letter Day has recently been released on Blu Ray and DVD and is available for streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

Cameron Macgowan is a Canadian writer, director, and producer whose work has won awards and garnered critical acclaim at international film festivals across the world including the Toronto International Film Festival, SXSW and Fantasia. Red Letter Day, his first feature film as a Writer/Director, premiered at the Cinequest Film Festival in 2019.

Murray Leeder is a Research Affiliate at the University of Manitoba and holds a Ph.D. from Carleton University. He the author of Horror Film: A Critical Introduction (Bloomsbury, 2018), The Modern Supernatural and the Beginnings of Cinema (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017) and Halloween (Auteur, 2014), editor of Cinematic Ghosts: Haunting and Spectrality from Silent Cinema to the Digital Era (Bloomsbury, 2015) and ReFocus: The Films of William Castle (Edinburgh University Press, 2018), as well as numerous articles and book chapters.