Growing up in Calgary, I mostly perceived the Stampede – for all its lofty self-billing as “The Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth” – as a local phenomenon, with only a dim awareness of its much larger public profile. So, it was a touch disorienting when Spider-Man paid the Stampede a visit in The Amazing Spider-Man comic(Issue 4, 1992), or to hear the Stampede mentioned on M*A*S*H (“No Sweat,” 1981). Such was a child’s naivety, but I suspect most Calgarians would be surprised at the extent Stampede’s profile was spread via the media, and especially through Hollywood films including The Calgary Stampede (1925), The Girl from Calgary (1932) and Northwest Stampede (1948). These texts have been interestingly absent from most treatments of the Stampede’s history1

The Calgary Stampede began in 1912 as a six-day event, founded by American trick roper and showman Guy Weadick. Weadick staged a second Stampede in Winnipeg the following year, and then again in Calgary in 1919. It became a Calgary annual event in 1923. The Stampede arrived in a media culture hungry for images of the vanished frontier. From 1870 or so, touring “Wild West shows” gave Easterners a taste of “authentic” frontier experience, and this phenomenon intersected with cinema early on. Thomas Edison made recordings of Buffalo Bill’s travelling company as early as 1894.

In time, the Western film succeeded the Wild West Show as the prime vehicle for the continued propagation of the myths and iconographies of the “Old West” period that, insofar as it ever existed, ended in the United States by the late 19th century. Westerns were the single most prolific genre in silent-era Hollywood and were astonishingly important in the establishment of the American film industry. The later settlement of what became Western Canada allowed for the narrative that the “Old West” still existed north of the border. The phrase “Last Best West” marketed the Canadian prairies to potential immigrants overseas – a promise that Canada represented the last bastion of “authentic” frontier experience, promising a part in nation-building. The Stampede was designed in no small part to promote and profit off of that narrative. Weadick maintained that it was “not a show but a genuine competitive annual tournament, participated in by genuine Westerners.”2The Stampede forever affixed Calgary to the iconographies and mythologies of the West, resulting in the tension between urban commerce and rural nostalgia that lingers in the city’s brand today.

It is no surprise that the Stampede and the film industry would not take long to intersect. Two different motion picture companies shot films at the initial 1912 event,3and Weadick himself would later fund and star in a rare Canadian feature film for the period called His Destiny (1928).4Subsequently there were documentary shorts made at the Stampede: notably the NFB’s Bronco Busters (1946) and Warner Bros.’ The Calgary Stampede (1948). There were also films shot but not set at the Stampede including Bruce Boetticher’s film Bronco Buster (1952).

I want to focus on American fiction films that were made and took place at the Stampede, melding modes of fiction with the tourist film while also operating within familiar generic confines (mainly, the Western). These films were made principally for American and international audiences and thus are somewhat strange viewing for locals. Canadian historian Pierre Berton’s book Hollywood’s Canada: The Americanization of Our National Image (1975) discusses the strange phenomenon of American-made films set in Canada, which normally treat the entire country as an undifferentiated forested landscape, unspoiled, and populated by a hardened frontier breed.5These Calgary-specific Stampede films are of that ilk yet slightly more specialized, emphasizing ranching, and especially rodeo, in their mix of exotic signifiers.

The star of 1925’s The Calgary Stampede, Nebraska-born Hoot Gibson, a champion rodeo rider, even won the Steer Roping Championship at the first Calgary Stampede in 1912. By the mid-1920s, he was one of the top Western stars and one of the top ten box-office draws overall.6July 1925 found him was back in Calgary as Parade Marshal for the Calgary Stampede, an event staged for the film. A few months earlier, the Calgary Herald announced “Universal’s Hoot Gibson To Be at Calgary Stampede,” citing the economic benefits of the presence of such a celebrity in the city.

No low-budget programmer, the film The Calgary Stampede was made under Universal Jewel label, Universal’s prestige brand of the era. It also had a novelization by Raymond L. Schrock, entitled The Calgary Stampede: A Story of the Canadian Plains (1925).7The film proudly announces that it was shot in Calgary in its first moments. Hoot Gibson plays Dan Malloy, a cowboy travelling across Canada performing in rodeos and working as a hand. Interestingly, Malloy is specified as an American in a single intertitle. The plot would be no different if he were Canadian, so this must be a concession to American audiences, offering the assurance that it is their countryman anchoring the narrative in this exotic yet familiar land.

Malloy specializes in the spectacular and dangerous “Roman racing,” done while standing on two horses simultaneously. Racial identity in the West is an interestingly prominent concern in The Calgary Stampede: Malloy falls in love with Marie La Farge (Virginia Brown Faire), whose father, a game warden at a buffalo preserve, dislikes Malloy’s Irish name. La Farge is killed and Malloy is blamed; the real killer is the film’s villain Burgess (Jim Corey), his crime concealed by his lover Neevah (Inez Seabury), a “half-breed” maid working for the La Farge family. Neevah, a sort of Canadian variation on the manipulative mixed-race housekeeper and seductress Lydia in D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), is the film’s most distressing feature.

Wanted for the murder of La Farge, Malloy works as a ranch hand near Calgary. Though he hides his prowess, he also risks secret horse rides under the cover of night and draws the suspicion of the local Mountie. Events converge at the Stampede, where Malloy’s employer recklessly bets his ranch on the Roman race. When the original rider is injured, Malloy suddenly comes out of both hiding and retirement to win the race. Everyone is conveniently in place to reveal the villain, exonerate Malloy, save the ranch, and reunite the heterosexual couple.

The Stampede forever affixed Calgary to the iconographies and mythologies of the West, resulting in the tension between urban commerce and rural nostalgia that lingers in the city’s brand today.

In its third act, The Calgary Stampede essentially pauses its narrative and becomes a travelogue about the “Calgary Jubilee and Stampede,” showing us some of the parade and numerous rodeo events. The event is described in lavish terms that surely drove tourism: “Canada’s great annual event”, and a “great epic of the West – the annual Mecca for lovers of skill and daring from every corner of the globe.”8The loftiest intertitle reads: “Like the great tournaments of King Arthur’s day – – a new chivalry, born of a race of empire builders.”9The film is unsubtle in building a mythological framework for the Canadian West, with Calgary as a kind of new Rome, complete with its set of gladiators performing in spectacular and dangerous feats of sport.

It is likely due to the success of The Calgary Stampede that, seven years later, The Girl from Calgary, seems to assume that the viewer does not need Calgary or the Stampede explained to them. Made by the “Poverty Row” studio Monogram,10The Girl from Calgary is not even a Western; it was billed at the time as “a gay musical” or “a musical comedy.” Though only the beginning segment takes place in Calgary and the action leaves the city quickly, throughout “Calgary” continues to signify a kind of uncomplicated provincial lifestyle. It stars Fifi D’Orsay as Fifi Folette, the titular “girl.” The fact that a French Canadian (the actress hailed from Montréal) hails from Calgary is not something the film presents as strange; indeed, a French Canadian leading lady is a feature it has in common with The Calgary Stampede. D’Orsay, for a time Hollywood’s premier French bombshell despite never having been to France, reportedly claimed “I tried to convince them that a French accent would be more believable in Montréal than in Calgary” and that the director replied, “I don’t think Calgary will be out of place for a Frenchwoman. After all, it isn’t very far from Paris, is it!”11

The Girl from Calgary starts with an image of a Stampede poster and seven minutes of newsreel footage, including showing the Stampede Parade marching past the Hudson’s Bay building on 7th Avenue SW and some grandstand activities with Indigenous performers and various rodeo events. This sequence was apparently originally presented in colour, though it only survives in black and white.12It even has a silent-era style intertitle, declaring “Calgary’s Day of Days.”13It then introduces the protagonist Fifi, an accomplished bronco buster by day and nightclub singer by night. Two talent agents recruit her to come perform in the United States; the “Calgary Publicity Bureau” agrees to fund her trip to a beauty contest in Atlantic City, citing the publicity value. Fifi is “Miss Calgary” at the beauty show, advertises sand baths as the “Girl from Calgary”, and then becomes a Broadway performer. The remainder of the film is a fairly typical showbiz melodrama about the seductions of wealth and fame; the fact that she was a rodeo performer ceases to matter rather quickly. Perhaps rightly obscure – even Berton seems to have overlooked it – The Girl from Calgary is a peculiar, tonally disjointed musical comedy worth seeing for D’Orsay’s charm and the documentary footage of the Stampede.

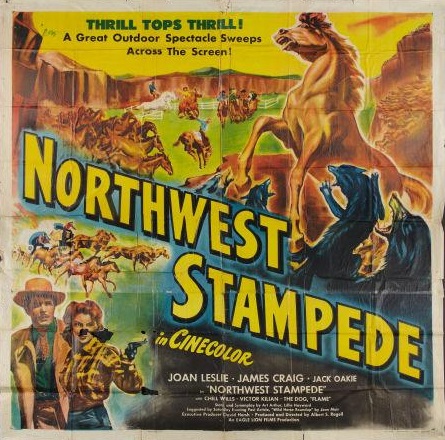

Made 16 years later, the colour Western Northwest Stampede is a considerably more lavish production. It seems to repurpose a few elements from The Calgary Stampede, including a rodeo champion posing as a lowly ranch hand, and a climactic race at the Stampede that also resolves a financial dispute. It takes place in Turner Valley, Alberta and contains plenty of Alberta location footage, including some stunning vistas of the Rockies. After a title card “the people of Lake Louise, Banff and Calgary for their cooperation in this picture against the backdrop of their beautiful vacation land”14, a male voice booms: “This is the high river country of the great Northwest - unspoiled by man, a region of cool, crystal lakes and towering, snow-capped mountains, where rimrock ledges climb up toward the timberline”15over postcard imagery.

This travelogue-style intro slides into the film’s fictional narrative, centered on the Bar-B Ranch. Rodeo champion Dan Bennett (James Craig) was raised there but has not been back for years, working the circuit in the States. Returning after his father’s death, he is surprised to learn that the new foreman is a hyper-competent woman, Chris Johnson (Joan Leslie), herself a former rodeo queen. Their romantic sparring plays out against a subplot about an untameable wild stallion who leads a pack of wild horses in the mountains but is actually fated to be domesticated. Bennett is in Johnson’s debt, which he hopes to overcome by winning in rodeo events at the Calgary Stampede; she comes out of retirement up to compete against him in the same events.

Northwest Stampede is most notable for its attractive Alberta landscapes and the depiction of Chris Johnson as a capable woman operating in a hyper-masculine regime, whose courtship with Dan Bennett is fairly even-handed. Northwest Stampede received a negative review in the Calgary Herald, however, saying that its makers had “no knowledge of the Canadian west and its ranch customs [and] proceeded to hash it up as only Hollywood can do it.”16After cataloging its many inaccuracies (including the fact that “a girl hasn’t ridden in competition in the Calgary Stampede since 1912”17– the author could lob the same critique against The Girl from Calgary), the review concludes with: “As a true representation of the world-famous Calgary Stampede, Northwest Stampede is a washout . . . I’m not saying you should not see Northwest Stampede. Personally, I think you should—even if it is only for a laugh.”18Interestingly, for this review at least, “Hollywood” is now a bad object that misrepresents the “true” character of the Stampede, which is an institution heavily shaped by Hollywood representation from early in its existence.

The film is unsubtle in building a mythological framework for the Canadian West, with Calgary as a kind of new Rome, complete with its set of gladiators performing in spectacular and dangerous feats of sport.

What do these three American-made, Calgary-set films have in common? In addition to mode-shifting between fiction and documentary, each involves cross-border interactions of some kind – an American cowboy in Canada, a Canadian cowgirl in America, and a Canadian cowboy who has become famous in America. In none of them does Canada simply exist without reference to the U.S. They are all set in the present day, thus promoting the idea that an authentic frontier experience persisted in the Canadian West even into the postwar period, that “last best West”. The Calgary Stampede even explicitly describes the Stampede as the “last stand of the old, reckless west."19The Indigenous characters in each film feature literally as elements of the Stampede’s mise-en-scène with no role besides simply appearing. The exception is the duplicitous Neevah, who ultimately reveals the real murderer of Marie’s father only out of romantic jealousy. While ethnic variation exists (Frenchness and Irishness), the primacy of white habitation is repeatedly reaffirmed, legitimated through displays of skill and bravery in the hazardous arena of the rodeo by both men and women.

As I write this, it has just been announced there will be no Calgary Stampede held for the first time since it became annual in 1923. It persisted through wars and depressions, but has been felled by COVID-19. If nothing else, these films, foreign-produced though they may be, speak to the psychic weight of the Stampede in Calgary’s collective imagination, and why its cancellation is such a momentous blow. It would seem appropriate to view these films in lieu.

The Girl from Calgary and Northwest Stampede both currently stream on YouTube. The Girl from Calgary is also available on DVD from Alpha Video, as is The Calgary Stampede from Grapevine Video.