In Canadian film and culture, the archetype of “the pioneer woman” often depicts women as homebound, alone both emotionally and physically, and struggling to understand their limited role among men. Her struggle leads to a descent into isolation and loneliness, where the landscape begins to feel too flat to comprehend, too enormous to take in and control.1

The rise of the female perspective in Western film with the pioneer woman trope intended to work against idealized portrayals of settlement life often found in art made by men. However, it continues to perpetuate female helplessness, and negate Indigenous perspectives, presenting a Eurocentric view of the land. While the mere presence of the female gaze on the farm, the land, and in the family in Western film was once ground-breaking, it’s now worth considering how this perspective has further evolved in cinema as well as how the pioneer woman trope, and the limited roles of women in the landscape, has been reinforced, questioned, or exploded by filmmakers working today. From Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978) to Kelly Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff (2010), and Sandi Somers’s Ice Blue (2017) to Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge (2017), the pioneer woman trope in film has evolved, challenging the notion that “a pioneering world…is a man’s world”—specifically, a white man’s world—in varying, complicated ways.2These four films represent an evolution of the pioneer woman trope and her relationship to the land, complicating our understanding of this archetype. Can the open landscape be something beyond a source of repression and isolation for female characters in film? And if so, how does this shift affect the viewer’s experience of these landscapes?

The frontier in the film moves beyond merely physical and becomes a state of mind: a lonely, constraining place that holds existential possibilities.

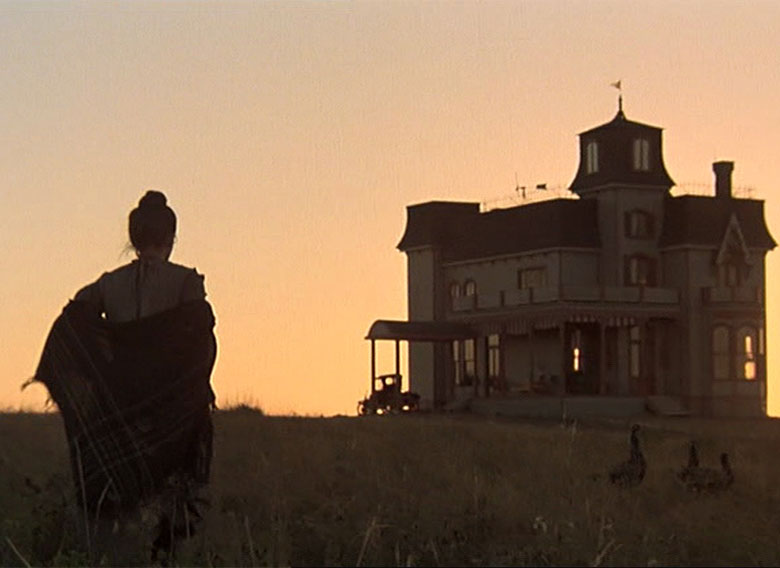

Malick’s Days of Heaven is a story of deception and romance between two drifters and a wealthy farmer, but the true focus seems to be on the landscape itself. Shot in the ghost town of Whiskey Gap, Alberta, and sections of Heritage Park, Malick’s cinematographer Néstor Almendros uses primarily natural light, creating images that feel almost like documentation of the land, and acting almost like its surveyor. Though the film is narrated by a young girl, the characters never appear as alive as the landscape. The most moving images in the film show the bliss and violence of nature, stalks of wheat shifting in the wind like water, screaming locus falling from the sky, and the stark flat land behind the bent backs of the workers in the fields. Intimacy in the film comes not from the performances or the plain speech of the narrator but from the way landscape is portrayed, a spectacle that becomes its own character. Though beautiful to look at and precise in its imagery, Malick’s film is still centralized around a typical Western representation of the land and gender roles, where the landscape is idealized and the character development tends to fall into what one might expect from a classic pro-colonial Western story.

Three decades later, Kelly Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff approaches the open landscape in a markedly different way, upending classic Western film tropes in the story of a group of American settlers searching for fertile land in 1845. As the group moves through the plains of Oregon in rickety ox-wagons, nothing separates the characters from the landscape surrounding them. Quickly, the narrative perspective shifts to the women in the group, holding the rope for the wagons while their husbands huddle together to discuss whether or not they can trust their guide. The gender dynamics in the film follow what was standard for pioneer times—the women build the fires, knead the bread, and wash the clothing—but the three female characters hold a quiet power, their faces partly hidden by wide brimmed bonnets. The film allows the women to express doubt in the enterprise of settling the land, setting up a kind of internal frontier that the characters must confront and wrestle with. Reichardt intersperses the women’s faces and quiet discussions by fire light with images of the expanse, sometimes superimposing one landscape on top of another so that characters appear to be floating in nothingness before the image places them on plains of cracked dirt. These transitions give the land a destabilizing effect, reinforcing the doubt and uncertainty forming in the group as they walk 10 miles a day across unbroken land towards potentially nothing. The frontier in the film moves beyond merely physical and becomes a state of mind: a lonely, constraining place that holds existential possibilities.

The defining moment in Meek’s Cutoff occurs when Emily Tetherow (Michelle Williams) holds a loaded gun to the group’s shifty guide to protect a character they simply call “the Indian” (Rod Rondeaux). Displaying a kind of colonial saviour moment only possible in a tale about settlers seeking a new land, this scene links two disempowered groups in the film together: women and Indigenous people. Out of an effort to accurately re-create the patriarchal, ignorant, and racist culture of the time—which still persists—the film does not elucidate the contexts, complexities, and agency of the Indigenous character. Williams’s Emily Tetherow however embodies many of the more nuanced characteristics of a pioneer woman, with her strength to accept adversity and her courage to try to shift what happens on the frontier. By giving the female characters agency to doubt and defend themselves, Reichardt succeeds at exploring new approaches to landscape and female identity, albeit at the expense of the Indigenous character’s agency.

If Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff probes new ground for female agency, Coralie Fargeat’s 2017 film Revenge rips it apart into a female-centred redemption tale. A French film that premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2017, Revenge begins with the literal male gaze, zooming out from the eyes of Richard, a wealthy married man wearing aviator sunglasses that reflect the stark beauty of the desert. We see him escort a blonde, lollipop-sucking mistress named Jen from his private helicopter. We watch him watch her in his sprawling home in the red hills of Morocco, and later, his two male companions watch Jen like prey, sometimes through binoculars, sometimes simply leering right at her. The film shows her flaunting her body in their presence, as if begging the viewer to blame Jen for what happens to her later. She dances with a man who will rape her, she flirts with men who will witness or acknowledge the rape happened and attempt to destroy her to protect themselves.

Her relationship to the landscape emerges out of necessity and she must find a way to use it to her advantage, to make the land a place of power where she can exert dominance and control.

When Jen awakes from her hallucinatory trip in a cave, after surviving attempted murder by the men, she has been reborn into a half-naked bad ass, a common horror trope given a female-centred tinge. Once reborn, she has no choice but to take on the unrelenting heat and barrenness of the land to survive. Her relationship to the landscape emerges out of necessity and she must find a way to use it to her advantage, to make the land a place of power where she can exert dominance and control. “The desert is sublime, but merciless with the careless,” one of the men says as they scour the desert hills for signs of her, this woman who will not die and ultimately be the bloody end to them all.

The use of rape as a character motivator in the film, where the character experiences violent sexual trauma to find power can be seen as problematic, a gender flip that does not seem as defiant as it appears. However, the film seems to intentionally set us up by playing into our expectations of a female character type like Jen and shocking us with her bloody, unrelenting thirst for revenge. In this way, the film becomes an adept metaphor for how rape culture works: the men actively seek to destroy the woman they have wronged. This setup also challenges our expectations of what a woman like Jen, the mistress who would likely be knocked off first in a typical horror film, can do in the wilderness, eluding and besting each man as they try to hunt her down. Revenge upends a familiar narrative, where women are victims, dead bodies in a landscape with no power or agency.

The farm, the film seems to suggest, is a source of madness. It clearly views rural life as problematic and romanticizes the city, a capitalist, colonial skew on female identity.

In the case of Sandi Somers’s Ice Blue, a young woman locks herself in the wood barn on her father’s land and breaks down, her howls merging with the low moans of the animals. Shot on a farm near Millarville, Alberta, Somers uses the open expanse of the prairies to great effect, contrasting the isolation and claustrophobia consuming the young protagonist Arielle with the soft pink and gold hues of an open sky. Her father, a controlling, violent patriarch, has entrapped her mother, and now her, in this isolated place, referred to as “The Compound” or “The Farm.” Ice Blue not only follows a cinematic tradition of landscape as theater, where the land is a controlled spectacle linking the visual to character,3 it also presents a modern version of the most common female trope in Western Canadian film, literature, and culture—a woman struggling to exist in rural, open spaces.

The landscapes in Ice Blue run cool, with brown, blue, and light yellow tones, and when there is blood on screen, it’s a small trickle on the skin. The film opens with the protagonist Arielle screaming by a frozen lake. It reveals itself to be a dream and in reality Arielle is a composed, quiet teenage girl, homeschooled, living with her father on a beaver farm. The farm is a place where Arielle feels safe and also afraid, especially at night when she is left alone by her father so he can drink and sleep around. As she yearns for her absent mother and dates a guy from the city, the farm begins to feel repressive and stagnate, too removed from the rest of the world. Throughout the film, the farm is portrayed as a place where animals are killed, people lie, your closest family members try to harm you, and the chances of getting out are slim to none. When her absent mother appears one night, she tells Arielle that the farm will trap her forever in isolation and advises her daughter to get out. The farm begins to reflect her father’s controlling and abusive nature. The goats dry up, the beavers begin to die, and the farm appears more oppressive than picturesque. Arielle tries to rebel her way out of rural life but her role as the locked-away daughter, protected over by her father, is never overcome. When Arielle holds a gun to her father, she mirrors Michelle Williams in Meek’s Cutoff, but rather than simply threaten violence, she pulls the trigger.

Ultimately, the film tells a coming of age story that is also a rebuke of rural life, where the farm is a source of violence and repression, while the city is an abstract place that represents freedom and choice. The narrow view of landscape in the film, as a source of repression places limitations on the characters that they are never able to operate beyond. Like her mother, Arielle can never escape her isolation on the farm, even when it is revealed that she has gone insane and never reaches the city, or becomes truly free. For the female characters in Ice Blue, rural life either leads to violence or insanity. The farm, the film seems to suggest, is a source of madness. It clearly views rural life as problematic and romanticizes the city, a capitalist, colonial skew on female identity.

The legacy of cinema is inevitably linked to the history of imperialism, where representations of the “Other” are always presented on the backdrop of colonialism.

Though these films all interrogate the ways in which landscape can reflect or refract character, particularly female identity, there is still other framing that can be done around what the land can signify in film. Viewing the land as oppressive, to be escaped or overcome, can be seen as a primarily Eurocentric perspective, where the city is romanticized as a place of freedom, a place to be powerful.4 The legacy of cinema is inevitably linked to the history of imperialism, where representations of the “Other” are always presented on the backdrop of colonialism.5 With this in mind, these four films run counter to Indigenous perceptions of the land and its relationship to gender and identity, a perspective that is often misrepresented or ignored. How can the existing frontiers in Canadian film be pushed to include new representations of landscape? How can filmmakers consider the land from different perspectives and in more nuanced ways? The landscape waits, ahead.