When night descends on Montréal, another city wakes up. Our own internal clocks set off a silent alarm inside our minds when the sun sets. Time for fun, sleep, love, or a little madness. Films and art history have taught us that day people are different from night people, day scenes are unlike night scenes. Edward Hopper painted night scenes to communicate something different in the air. Forough Farrokzhad shot the 1963 documentary film The House is Black at high noon, to expose in plain light the scars of leprosy.

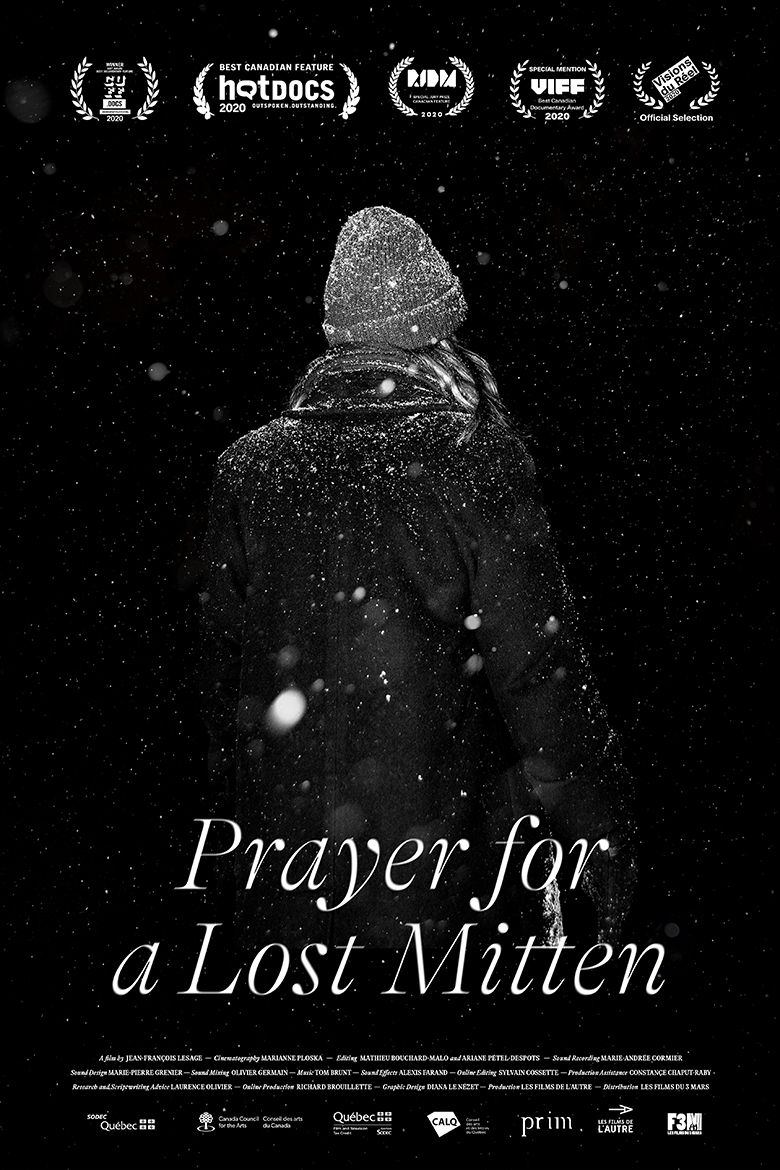

In Jean-Francois Lesage’s 2020 documentary, Prière pour une mitaine perdu (Prayer for a lost mitten), we watch, with voyeur intimacy, the night thoughts of various citizens in Montréal, as they discuss what they have lost in their lives. It’s a free-flowing piece that begins in the lost and found department of the STM (société de transport de Montréal), looking for their lost mittens, wallets, and toques. Lesage follows these people to their homes and apartments, asking “What did this item mean to you?”

With nightfall comes an enveloping snowstorm that muffles out the sounds of the city, and unifies every intersection, rooftop, and Mount-Royal Park, with thick gales of snow. Lesage deliberately does not name the subjects interviewed, or for that matter, give us a traditional documentary structure of statistics, locations, geographies, or interjections. La Mitaine (as Lesage likes to call it) is an observational poem -- though I don’t like referring to works as other mediums when they are not, this is a documentary after all. But can a documented piece of reality be imbued with something else? Something beyond a point of view? Perhaps a spirit, like the spirit of snow, winter, loss, or simply, the memories we still haven’t let go.

Mitaine won the Hot Docs Best Canadian Feature in 2020, as well as Best Feature Documentary award at CUFF (Calgary Underground Film Festival). The film continues to resonate with audiences across Canada and in the French speaking regions of the world, and I suspect for one simple reason: everyone has lost something. We all carry a little space in our heart for a lost item, whether it is in fact a mitten, or a person, or a time. With this film, there is something found in our collective loss. I spoke to Jean-Francois Lesage while in quarantine, just after he found out he won at CUFF.1

Guillaume Carlier (GC): Was it a surprise when you won?

Jean-Francois Lesage (JL): Yes, it was a surprise. Usually in a festival you would be going to the closing ceremony, then there would be this anxiety, “Will I win or no?” This year is very different, just in the middle of the day you get an email letting you know you won. I don’t complain about that, it cuts all the anxiety: “Oh I don’t want to think about the prizes, but I’m still thinking about the prizes. I’m still thinking about it obsessively.” Actually, I prefer that it is a surprise. I won three prizes this year. At CUFF in Calgary, at RIDM, there was just an email. I kind of like that.

GC: I’m curious, when you won, did you tell the people in the documentary?

JL: I wrote to them. Because all these festivals are online, I don’t get to meet the public, but I got a lot of little messages about the film, so I took a couple of these, and mentioned the prize, and a few positive critiques of the film, and sent that to all the characters of the film.

GC: It’s such a loose nebulous film, I wonder if they are surprised by the success of the film, since they are so much a part of it too?

JL: Yes, we still didn’t have a premier in person. I hope when we are all vaccinated, I can invite all the characters to the premier of the film, because then they can see how the public relates to the film, and people can go and see them and talk to them. That experience is missing for them.

GC: It’s almost like it wasn’t real.

JL: But I’m keeping in touch with little emails, that something is happening with this film, this experience they had in the cold winter nights of 2019.

GC: Where did the idea for the film come from?

JL: I wanted to make a film about longing. We don’t have this word in French, but it’s like, désir profond (a profound desire), this longing. I did observe people claiming objects from the STM. And I thought it would be a good starting point to make a film about loss, and the longing to get something back. That’s how it started, but there was all kinds of different ideas, not necessarily coming at the same time.

I also thought that the winter was the best season to make a film about loss, because everything disappears under the snow. I wanted this film to be shot at night. I found that the first images of the film should be black and white. So it’s like a constellation of ideas, and once you put it down on paper, eventually you can go out and make it real. But there is a big gap from how easy it is to write it down, and how much harder it is to shoot and make a film, at minus thirty in the cold nights of Montreal.

GC: Brave crew, very brave crew.

JL: Very brave! It’s a small crew, but it’s people that I work with from one film to the other. It was a lot of tension this time, there was a lot of tension this time. Even if they were friends, even if we did other films together, it was much more difficult. I blame the winter for that, the cold winter.

GC: But in the end, you can comfort yourself with the images, the images are very beautiful. Especially for Montreal. I think for Montrealers, we know that’s a taxing cold.

JL: It’s funny because to help me in my creative process, I tried to forget about the shooting, and deal with these pictures as if they were found in a shoebox, like some found footage. I tried to forget about the shooting experience, which was a lot of difficult moments. I had to drive the van, the whole crew, at late hours at night, I would have to find parking during these snowstorms, on the street. It was a nightmare. You are exhausted, you’ve been shooting for ten hours, and then you don’t find a parking spot. There’s lots of memories like this.

GC: Was it the hardest film you have done?

JL: Yes, easily yes.

GC: Can you explain a bit more about starting a documentary from a feeling rather than a subject matter?

JL: I really tried to build an atmosphere, so I like to see my films as mood pieces. It starts with what I will imagine, but my material comes from reality. It’s real people with real conversations with real places. But I like to infuse this material from reality with an atmosphere, to inject something into it, to inject life into life, to create a dense atmospheric world, from one world to another. So yes, it starts with a feeling, it starts with loss. [...] I start from a feeling, but it has to be anchored in reality, it has to be anchored in the words of people I don’t know, and from their words, I will try to build something that I can relate to. There is a quest of my own, there’s always my own questions at the center of my work.

"I’m optimistic for cinema. It always reinvents itself."

GC: I’m curious what is the process of selecting the characters?

JL: Another idea that helps me make films, is that I bet on the fact that anybody, like all of us, could be possibly the subject of a documentary film. So I start from that premise. But still I do some selection. For example, at the STM I spent two days there, filming almost 200 people, claiming objects…I watched the footage and selected 30 people. We watched how they were with the clerk at the STM, and how their interaction went.

Then I phoned thirty people, then we conducted interviews with these people, then after that we filmed them in the winter in the snow, doing some kind of nocturnal activities in the snow. And then in the fourth activity, we asked them to invite their friends or family over for drinks or dinner. And we filmed these dinners, or apéro (aperitif) with a friend. So there were different steps. It started with 200 people, then 30, then in the film there are about ten main people that we meet.

GC: You allowed yourself the structure to allow yourself to be open.

JL: Absolutely, but towards the end of the process, to be transparent, towards the last week of shooting, I’m more “I want this, not this.” I mean, I’m fishing with a big net, but as I’m shooting, the net is becoming smaller and smaller, I will intervene more. I did intervene in all these dinners. For example, the person that we found at the STM, during these dinners will become my ambassador. She will have my questions. After two or three hours of dinner, she will ask these questions to her friends. So, there are interventions, but they start from the people.

GC: What I like about the structure is that it's not auteur driven. It starts with the subjects, and you create the story with the subjects. In a way it’s more of an equal footing.

JL: Yes, and the film will be written in the editing room. This is when we find the story. There will be nice scenes, but in the edit we will see how one scene talks to another. It’s a long and mysterious process but we will find an itinerary in the material in the editing. That’s how we structure it.

GC: The Brazilian documentary filmmaker Eduouardo Coutinho has a quote that I think relates to your film: “Chance is the flower of reality.”

JL: Yes, I relate to that. I like documentary filmmaking because you are moving towards the unknown. When you talk to narrative filmmakers they say there is the unknown as well, because you don’t know what the actor will bring out in the material. But really in documentaries there are so many things that go wrong or happen, that’s what excites me. We can go out in the night, in a snowstorm, and we don't find anything. Sometimes there’s only a lonely cat walking in the back alley. Or sometimes it just never stops. I’m always surprised how in one night we might get four scenes in the film, and another night we will get ten seconds of good material. I really like the process of going into the unknown, but there is a point where I have to set some limits for what we are going to fish for.

GC: What limitations from conventional documentary filmmaking are you resisting? I can feel that there are conventions that you are getting rid of. For instance, the lack of names, or having a rigid shooting schedule. It seems like you guys didn’t have one.

JL: I feel like I like traditional documentaries, but I feel like I build on this. For me the interviews were just an excuse to go and discover these people in their homes and apartments, and seeing how they live. Like they live with their daughter in this part of town, or suddenly I would activate my imagination with what we could do with the protagonist. But I thought the interviews would not be in the film. But they are! It’s interesting, because we thought they were so rich, so we put them in. We thought, okay people who like traditional docs will like these interviews, but then I like to push the boundaries and go somewhere else. It’s the same thing with the music in the film. It’s a leitmotif of jazz music that comes back, but at one point we can just abandon it and have something else and have something more nostalgic. I like that you can follow one rule, but then go to another world, without noticing it.

GC: Do you think you could make this film earlier in your career?

JL: No. I feel that you learn how to make films by making films. And from one film to another, I have a feeling that my vision is becoming more precise. No, I don’t think I could’ve come up with this at the beginning. There are thoughts that are given to so many aspects to the film, before I even started. I feel like my vision is clear before anything is shot. It’s a paradox. I told you about this wonderful world of the unknown, but at the same time, what I found out is I want to have a vision with everything I can think of ahead. I like to have that space to do that. I like to already know what I want to create, what I want to create with the sound, the material. I like it to be more precise every time. So I feel there is an evolution for me as a filmmaker. For this film, a lot of things were prepared in some way. I hope to think there's a clearer vision from one film to another.

GC: There’s also the growth we experience from one film to another personally, knowing what we can do, and what personal limitations we can push. Or if you have to pull it back. If your ambition is too big and you have to pull back.

JL: For all my other films I shot myself, but in this film I didn’t shoot. There were occasions to resist the temptation to take the camera and move it somewhere else. And when I explained what I wanted instead, the result was much better. It’s a question of how you can communicate your vision to your crew.

GC: What did you learn about Montréal when you made this film?

JL: I learned many things. I did a film before in Gaspésie, and the people who said yes were extremely generous. But there was a lower ratio of people who said yes. Out of ten people I asked, two will say yes in Gaspésie. In Montreal, it was eight out of ten. That’s what I like about this city. If you come up with an artistic project, people are so open. Most people said yes! They signed and we saw them four times. I’m amazed by that. I really like this about Montréal. I also found so much inspiration from these people who were skiing, skating, at midnight or later on Mount Royal. They go outside, the winter is not torture for these people. They do stuff! This winter I want to do some stuff that these people do. I don’t want to just wait for winter to be over. And I love the diversity of the city. I find it interesting that it’s a francophone city in North America. I think there’s an openness to artists, to culture, that’s what I like about the city.

GC: On a more personal note, what have you lost? As a filmmaker or as an individual?

JL: When I thought about this film, it was more like a feeling of “Oh, this time of my life was great, but I didn’t enjoy it.” Time was just going through my fingers. It was a feeling of wow, that was a good time, but I was absorbed by something else. I wasn’t living in the moment. I wasn’t enjoying this precious time. It was this notion that made me want to do this film. When I was thinking about it, I was thinking about love relationships, but I also feel it’s also good sometimes not to find what you’ve lost. It could be interesting also, not to necessarily get back what you’ve lost.

G: No one ever says that, because they don’t want to admit it.

JL: Yes, well it’s nostalgia. I wanted to explore that feeling for myself. That was difficult also. Loss it's a very scary topic, somehow. It’s like an abyss, that you might not want to look inside too long. I was thinking with this topic, and I was going to hear really sad stories, and very heavy stories. How can I not get completely absorbed and sunk into these heavy stories? How can I keep my head above water? I figured my focus should be on the longing. So, what happens in the film is that yes, you will hear very sad stories, but I feel there’s still a thread to keep humour, some air, without denying these darker stories. We explore them, but at the same time, there’s always happier moments in the film.

GC: I think too, the choice of ending the film with collective hope rather than individual hope, can help. Especially because individual hope can be lonely, or even delusional. But collective hope is different. With the choir, that was a beautiful touch. It gives people the ability to make a ritual out of the loss. That’s what it is, it’s over. So now you have a marker in time, of getting together with a group of strangers and singing.

JL: That scene was so beautiful.

GC: Was it hard to convince people to do?

JFL No, not at all. Montréalers…[laughs] I met this man, André Papathomas, he had all these people in the audience sing their first name. He made it sound like a beautiful contemporary piece. He really brought something just by guiding us just like this. I’m not a singer, but I really felt something. I went for coffee with him [...] later, and I talked to him about the project, and I said could you make people sing about the objects they lost?

GC: It’s an unexpected turn, but it feels like an appropriate one.

JL: It was a strong moment in the shooting. Luckily we were inside and not freezing outside.

"Loss it's a very scary topic, somehow. It’s like an abyss, that you might not want to look inside too long."

GC: What do you think that cinema has lost?

JL: I’m optimistic for cinema. It always reinvents itself. For example, my love for cinema, it comes from films, it comes from references to other films, so it comes from my cinephilia. So, I feel that there are so many interesting films that are still being done, it can only grow. I don’t see it as dying. I don’t know, it’s a bit like literature. There’s no end to it. There’s creativity, plus there’s these great filmmakers who have explored many different forms, and we can still explore different forms. I’m still very confident for cinema.

It’s like a growing tree. So many films inspired me for La Mitaine. I was inspired by Gilles Groulx, Gilles Carle, great films from the sixties, La vie heureuse de Léopold Z. They were supposed to do short films with the NFB, but they decided to transform it, not follow rules, they made feature films that are super important now. But I was also inspired by this Swiss filmmaker Alain Tanner. I really like the films he did in the late sixties, early seventies. Where people would be sitting at a table having deep conversations around a dinner, very joyful conversations, even if they were difficult topics. I feel it’s like literature.

There’s a corpus of powerful work that resonates, and you can also explore yourself some new avenues. But for me all these references are very important. There are filmmakers today who don’t care about these films. There are filmmakers who are not cinephiles. I don’t know what they’re background is. They are proud not to watch films. Cinephilia doesn’t have to be the starting point. But in my case, it’s the starting point. It nourishes my own creative process.

GC: Has anyone reached out to say that the film has given them closure? That the film has helped them move past their loss?

JL: Some of the characters saw it, some didn’t. I know that with other films, the film I made just before The Hidden River, I like when people confide, I like intimacy. The couples in my previous film came to see me and said, we had that space to have that conversation and that was meaningful, but now we are not together anymore. It’s more about creating that space for confidence, for intimate conversation, then characters might have a moment of truth. I still don’t know about La Mitaine, I still haven’t heard back yet. But some people not in the film said to me that this film is a warm blanket for the incoming winter.

You can watch the trailer for Prayer for a Lost Mitten here: https://vimeo.com/394337507

For more about Jean-Francois Lesage: https://reals.quebec/jean-francoislesage