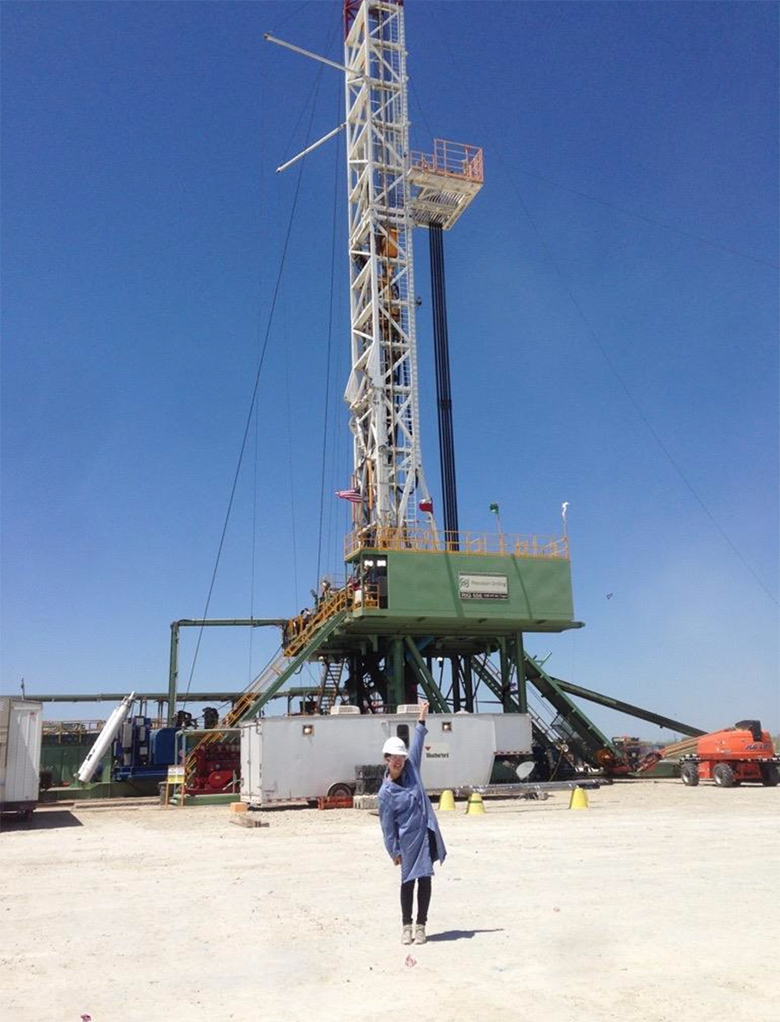

Awarded one of three 2017 Calgary Film Centre Production grants, Gillian McKercher is making her first feature-film, Circle of Steel, a satirical semi-autobiography based on McKercher’s experiences as a chemical engineer over the past four years. The film centres on Wendy, a young engineer struggling to acclimate to life in the oil and gas field. This article is the first of Luma Quarterly’s three-part series following the production of the film, and documenting Gillian’s experience as a first-time feature filmmaker.

This interview has been edited for length.

Ted Stenson: Can you tell me about the very beginning of this project? How long ago did you start working on it?

Gillian McKercher: The formal start was two years ago, in November 2015. The Sundance Institute has a program called Ignite for people age 24 and under, and I wanted to submit something for that, but it didn’t work out. But that was when I started following Sundance and I saw their Screenwriters Lab which was for May 2016, and I was like, ‘Okay, that’s my start point.’ So, I just had to make a script, partly I had also always wanted to do the Telefilm Micro-budget Production Program. I’ve been following the Micro-budget program since it first started—I attended the industry sessions at the Calgary International Film Festival and watched North Country Cinema be the winner in that first year. I knew I wanted to do a feature film but I could never find a cohesive narrative for it, so the Sundance thing was more of a challenge to just write a story. My first draft was just figuring out how to write. I didn’t even know what I wanted the story to be about, I was just figuring out how to write a script with a deadline. My first draft was based off of a very specific period of my engineering career, but I also felt the pressure to be political, and hit feminist topics, and be ‘relevant,’ but the story really suffered for that—it just felt soon the nose and very forced—but at the very least I finished a draft.

TS: Can you talk about your personal relationship to the story?

GM: I always wanted to be involved in film. I wanted to be an actress and then I wanted to be a screenwriter because I thought screenwriters had more power or at least they had more ability to tell a story. I’ve always been into celebrity culture, just being into actors as a kid and watching the Oscars. I think the Oscars educated me that there were other roles. And I thought, ‘Oh, the screenwriter is the one who writes the story—I want to do that,’ but then I learned that the screenwriter is limited and often the director is more in control. I started to learn more from watching a lot of DVD commentary tracks. I would watch like The Lord of the Rings (2001-03) commentary for three hours!

TS: That was your film school.

GM: Well, I really wanted to go to film school, but my Mom and I had a real conflict over that because no one in my family, on either side, has ever been in the arts or done anything like that. The arts just seemed intangible and ambiguous to them. The questions my Mom had—like, ‘How are you going to make money?’ or “Where are you going to find a job?”—I had no answers for. I did the CSIF Summer Media Arts Camp when I was 17 because I saw the poster at Tubby Dog. That was the summer before I went into Engineering at University of Calgary. Then I became a member of CSIF because the Programming Director Melanie Wilmink said, ‘You should write about your experience at the Arts Camp.’ Then I started writing for Answer Print and found out they had workshops, so I did the screenwriting workshop with Corey Lee and later that year did the Filmmaking as Poetic Imagery workshop with Sandi Somers. So that was my film school. This film was really fostered at CSIF: wanting to do the $100 Film Festival and applying and getting rejected and applying and getting rejected and then finally getting in with the FME (Film Music Explosion). And as I was going through school I would watch a lot of director’s commentaries.

TS: Never having written a feature before, how did you approach the writing phase? Did you just say, ‘I’m going to write a script and that will be the first thing’?

GM: Through reading a lot about celebrity culture, I think I always had the idea that the script came first and then there was this set trajectory. I had tried writing a feature that just never went anywhere, and was really frustrated with writing shorts because my shorts were like 20 or 30 pages long, which is very challenging to produce. With the Sundance Screenwriters Lab, I was just looking for a quick way to make a film. I just needed a carrot at the end to make me do it.I read a lot of scripts online and then would watch the movie. I had the scripts for the first three episodes of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003). You start to see the difference between scripts and the eventual films. I learned that in writing the script, it was just about getting things down on paper and, as the director, you could figure things out later. That was liberating because I knew I wanted to direct; I felt like I didn’t have to describe every little thing. But writing something based on my experience was really helpful.

TS: How many drafts did you end up doing?

GM: I’m working on my sixth ‘official’ draft. There have been five distributed drafts. The feedback I got from friends that read the script has been really helpful. I was accepted to the second round of the Sundance program that I applied for, which was a big surprise, and they wanted a full script within two weeks, so I had to incorporate all the changes I had been planning based on the feedback I received, and my own thoughts. I rewrote a second draft in basically a weekend. That was a crazy weekend. After the second draft was done, I knew that the deadline for the Telefilm Micro-budget grant was coming up, so I took some time and incorporated the changes I wanted to make. But once I started understanding the story better, it became much easier to trim down and shape the script, and at that point you aren’t so attached to the first draft anymore.

TS: Was it hard to get rid of things because of the autobiographical aspect of the script?

GM: It’s a balance. The story is informed by personal experience, but at the same time, it’s not a documentary. When I realized that, it was really liberating. The main character, Wendy, doesn’t have to experience everything I did. I realized she doesn’t have to have the same boss that I had. At that point you think, ‘Maybe she can do things that I didn’t.’ She can be an amalgamation and that better serves the story.

TS: Was it difficult to make those changes?

GM: It is important to surround yourself with people you trust and respect. People make suggestions, which you can try, but if they don’t work out, no one has to see that version. I’ve been open to trying things that other people have suggested. I was never tied to a specific plot or a specific chain of events. Gary Burns, for instance, suggested that I focus more on the field work aspect of engineering as opposed to the office environment. When I tried that, it made sense. And a lot of these changes helped the ideas I initially wanted to convey emerge more naturally.

TS: So, you started writing the script, you wrote a ton of drafts, and then you end up getting funding...

GM: Yeah, and rejection! I didn’t get into Sundance. I didn’t get the Women in the Director’s Chair grant. I didn’t get the Telefilm Micro-budget grant....

TS: But eventually you got funding through the Calgary Film Centre.

GM: Yes.

There’s a director from Edmonton named Eva Colmers who said, “To be a director means you only focus on directing. To be a filmmaker means you do everything."

TS: How has the project changed since that happened?

GM: There’s a director from Edmonton named Eva Colmers who said, “To be a director means you only focus on directing. To be a filmmaker means you do everything.” The funding is incredible, but it isn’t at a level when you can be a compartmentalized filmmaker. You’re still doing everything. Since I got the funding, it’s been a lot of production housekeeping: creating an incorporated ‘entity’ to hold the money, making sure I have the right kind of insurance, making sure I have the right contracts in place, do I go ACTRA (The Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists), do I not go ACTRA, how many shooting days...

TS: When do you start shooting?

GM: November 20th.

TS: And when did you receive the funding?

GM: The middle of May.

TS: That’s fast.

GM: Part of being green to this process is realizing how much pre-production happens immediately before shooting. I’ve already cast my two leads whereas a lot of productions, it seems, don’t even cast until two weeks before they shoot. Even locations, you can have people looking for locations up to the day that they’re shooting. We brought on a producer, Robyn Ho, who is helping with the production side of things so now I can focus more on directing—how does it have to look, trying to develop a visual style with the DOP, ensuring the production and costume design is going to be right, even trying to think about marketing strategies, making sure we capture the right things in production to support marketing later, thinking about the score... These are choices that I’ve been making in the past three months. It’s nice to be able to prepare some of these things ahead of time instead of having all of the choices being reactive, during or after the shooting.

TS: You’ve never done something on this scale before. What has it been like making these kind of decisions? And how are you figuring out what you need to get done, since so much of it falls on your shoulders?

GM: My engineering background has been really helpful. When I worked as a Project Engineer I would work on projects that cost half a million dollars, so the scale isn’t intimidating to me. And engineering projects are kind of comparable to film; you have a team and the project moves through stages. That has helped a lot.

TS: Because this is the first year the Calgary Film Centre is giving out this grant, you’re kind of a guinea pig.

GM: It’s true, but there are comparable programs like the Telefilm Micro-budget Program. Seeing what North Country Cinema did when they got that grant was helpful. I think it’s a benefit that for a lot of our key creatives, it’s their first time working on a feature film. I think that releases us from a lot of the expectations of conventional, unionized filmmaking.

In pre-production, the most difficult thing for me has been finding a balance between my independent sensibility and a more traditional way of filmmaking.

TS: How have you approached aspects of pre-production like casting now that you have more resources and options?

GM: The lead was cast in a really unconventional way. I didn’t know it was unconventional at the time. I met her, talked to her, and said, ‘Let’s do it.’ I didn’t even see her demo reel. Again, with my obsession with celebrity culture, I feel like I’ve read so many unconventional casting stories that it didn’t seem weird. Andrea Arnold cast American Honey (2016) by going to Florida during spring break and looking for random people. So, I know people have done it that way before. I am going to cast the supporting characters through a casting group just because of time. There are deterministic choices. The moment you decide to cast someone from ACTRA, you have to fully go ACTRA.

TS: What has been the most difficult part of pre-production?

GM: Development isn’t exactly pre-production but the most difficult thing about development is persevering, because you hear, ‘No,’ all the time. You have to have a singular focus. But in pre-production, the most difficult thing for me has been finding a balance between my independent sensibility and a more traditional way of filmmaking. I’m trying to organize things so that I can be flexible when it comes time to shoot while also respecting the fact that I need help to make it look the way I want. It’s also been difficult to delegate work and allow people to do their jobs. On an independent, low-budget film you often end up doing everything yourself. Now I’m in the position where it’s a detriment to try and do everything. It would be impossible. I’d be too burned out.

TS: What has surprised you about this process so far?

GM: Finding that people believe in my project and that people want to help me. I think there’s a perception that you’re serious if you’re making a feature film. It’s not just a hobby. And there’s a certain glamour with a feature film. People have personal connections to feature films. Most people don’t watch short films. But everyone has been to see a feature.

TS: From a more creative standpoint, what are you working on as you get ready to shoot?

GM: I like working with a shot list, even if on the day of shooting you don’t use it. It makes me feel prepared. I like to come with an idea, where I have it edited in my mind. That actually allows me to be more spontaneous. I’m not comfortable doing that until I have a baseline. So right now I’m trying to create a baseline.

Gillian McKercher is a Calgary-based filmmaker working in film and digital mediums. After graduated from chemical engineering at the University of Calgary in 2013, McKercher spent four years working in oil and gas while producing short films, documentaries, and screening her work at the Calgary International Film Festival (CIFF), and the Calgary Society of Independent Filmmakers (CSIF) $100 Film Festival. She was a BravoFACT Pitch Finalist at Calgary International Film Festival in 2016 and a participant in the Herland Mentorship Program through which she produced the short film Family Photo. She is the co-creator of The Calgary Collection, a web-series profiling Calgary’s folk music community. She began shooting Circle of Steel in late November 2017, and is scheduled to release the film in Fall 2018. Learn more about Gillian’s past and present projects at www.kinosum.com