Six years ago, a dear friend and I embarked on a journey to heal the wounds of our privileged suburban angst; an angst that drove our rusty green Toyota 4 Runner from the Canadian Rockies to the Mexican west coast. It was the vehicle for our freedom, a vehicle for experiencing land’s drama, for mitigating the diminution of space and time elapsed too quickly. We were lucid as naïve, quaint Canadian vistas faded into one of the world’s most heavily policed borders.

Nogales: the name of a town in Arizona or a town in Mexico’s Sonora state, or further still, the name of the border crossing between the two. The respective realities of these three Nogales are impossible to reconcile. Approaching the border from the north, we inevitably encountered the line of rusted metal running through Nogales, demarcating America and Mexico, bisecting what is meant to be one town, but in reality are two. Nogales is a butterfly, except she isn’t symmetrical. One wing is vibrant, the other—dusty.

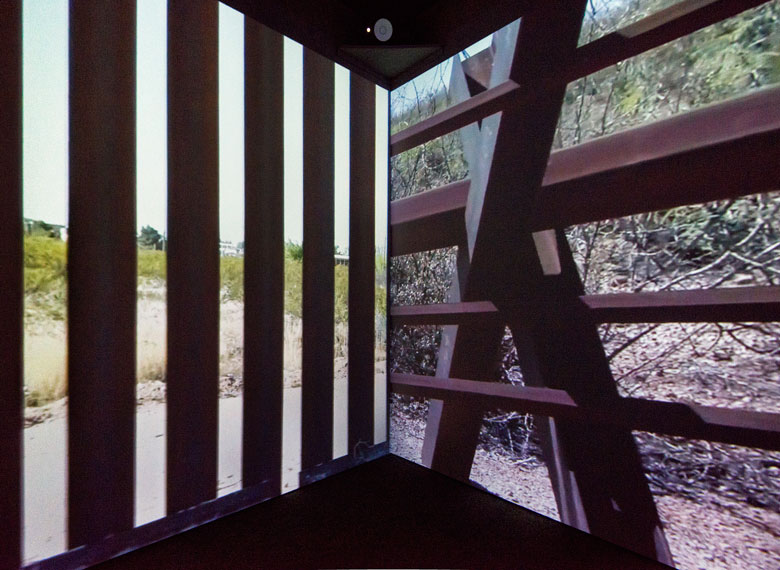

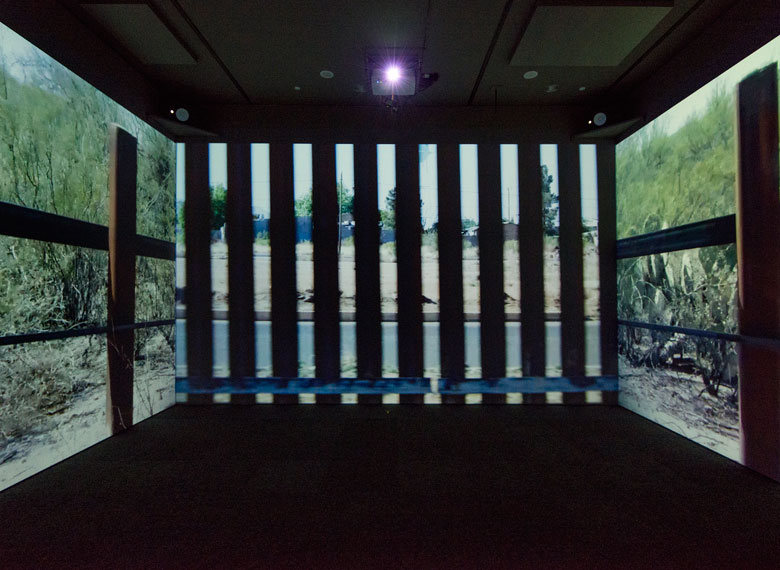

More fences flash by six years later—this time at Esker Foundation in Calgary, Alberta. Fences of different patterns, designs, and materials change and morph throughout Postcommodity’s four-channel projection, A Very Long Line, and I recognize something about my experience of the Nogales border. As rows of fences slow and accelerate by the camera, loud zooming and breaking of on-the-ground mechanical sounds accompany: a car speeding and braking, skidding, stopping. My senses are engulfed with palpitating light and discordant rhythms, each channel of the video work stretching crisply to the edge of its respective wall, wrapping seamlessly around the room. It is dizzying and disorientating, yet the movement cradles my senses with an emotional and physical claustrophobic vertigo. Being within the work is to be on both sides of the fence simultaneously. Territorial lines are blurred. I am both able to pass through a barrier, and restricted from doing so—with the same uneasiness and trepidation.

The fence, the focus of A Very Long Line, is the symbol of constructed nationalism and a tool to shift transborder discourse. In an earlier related project discussing and rejecting the US/Mexico border, Postcommodity’s monumental 2015 work Repellent Fences used a 2-mile-long temporary installation of enlarged bird repellent balloons. Postcommodity, a multidisciplinary art collective based out of Albuquerque, New Mexico, and comprised of Raven Chacon, Cristóbal Martínez, and Kade L. Twist, engages independent Indigenous narratives with the ever-expanding, culturally destabilizing, and violent global market.1 The repellent balloons used in Repellent Fences, ineffectively used on a smaller scale in backyards to deter unwanted birds, coincidentally use the same iconography and primary medicine colours—red, yellow, and black—Indigenous peoples from South America to Canada have used for thousands of years. These balloons, designed to communicate with birds—the spiritual mediators between physical and spiritual worlds for Indigenous peoples—act as scare eye balloons for spiritually and physically repelling the colonial, Western worldview.2 Creating a suture-line of balloons, Repellent Fences spanned and unified the US and Mexico at their border, symbolizing the pre- and post-colonial connection between the people and land of the Western Hemisphere in its entirety.3

The rows and rows of obscured suburban houses conjure uneasy feelings—a kind of doom, a bisection of identity, the threatening of a devouring and polarizing conventionalism.

The fences in A Very Long Line run in horizontal lines, then in tightly staggered vertical lines; most ominous are the heavy metal forms crossed to create forbidding Xs. I make out the landscape in the background through perforations in the fences as the pace slows—scenes of grassy fields, and occasionally suburban neighbourhoods, sprawling into the distance. Walking alongside the work, the fence appears to run parallel to my body, keeping pace, rendering the grassy landscape in a calm recognizable tone familiar to anyone at the helm of a road trip. However, the rows and rows of obscured suburban houses conjure uneasy feelings—a kind of doom, a bisection of identity, the threatening of a devouring and polarizing conventionalism—what I journeyed to escape six years ago.

Fences are built upon the notion that land ownership exists, while—much like capitalism and sovereignty—land ownership is an arbitrary notion. Upon leaving the gallery space and all the stimuli, the unrest and agitation woven into the installation is thrown into sharp relief. I reminisce on my brief border encounter, its torrid divide, wings yet unattached. In the era of Trump, and witnessing the rising strength of a bald-faced nativist mentality and the perpetuation of xenophobia, which side are you on?—a question that only exists because ‘fence’ exists.

View Postcommodity's A Very Long Line at the Esker Foundation until December 22, 2017.