Toronto-born director Ted Kotcheff’s career has spanned more than seven decades and includes credits ranging from beloved Canadiana The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1974) to Hollywood chart-toppers like First Blood (1982) and Weekend at Bernie’s (1989). Perhaps his greatest achievement however, is his most unlikely: the 1971 Australian thriller Wake in Fright.

Despite a highly acclaimed Cannes debut, the film struggled to find an audience and disappeared into total obscurity, unavailable for over four decades. In 2009, a restored version (selected by Martin Scorsese as a “Cannes Classic”) screened at Cannes, making it, along with Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1960), the only films to play at the festival twice.1Since 2009, the film has enjoyed a greatly deserved renaissance, with filmmakers and critics as various as Gaspar Noé, Roger Ebert, and Rex Reed singing its praises. Australian musician and screenwriter Nick Cave has given the film perhaps its greatest compliment, calling it “the best and most terrifying film about Australia in existence.”2

Wake in Fright also serves as a tantalizing ‘what-if’ to the history of Canadian cinema. Deeply influential to Australian New Wave filmmakers Peter Weir, George Miller, Bruce Beresford, and Fred Schepisi, Wake in Fright helped spur the kind of unique, homegrown feature film industry that Canada has long struggled to develop. While Kotcheff states the impossibility of making a film such as Wake in Fright in Canada at the time, he also acknowledges the influence of Canada’s landscape and colonial history on the film. Although inarguably an Australian movie, Wake in Fright is an intriguing footnote in the history of Canadian cinema, a footnote that hopefully leads to expanded inquiry as the film’s reputation and influence grows.

How anyone could ever live and work there I don’t know….the land would beat you down.

TS: How did you, a Canadian living in London, end up directing Wake in Fright?

TK: I had done a film in England with a writer who became a good friend—it was a British film called Two Gentlemen Sharing. I was living in England at the time. I had to leave Canada because, well, it was obvious, there was no film industry in Canada. You had two choices: either you went to America or you went to England to make films. I didn’t come back to Canada until I made The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. The Canadian Film Development Corporation had been created and there was a subsidy which helped me. That was my first Canadian film and I lived in Canada.

But, at that time, people like Norman Jewison went to Hollywood. He did an amazing job and got an Academy Award nomination. Arthur Hiller who made Love Story (1970) was another Canadian who went to Hollywood. But I went to England and my first three or four films were made in Britain. Tiara Tahiti (1960), with James Mason, was my first film. My second one was Room at the Top (1965) with Laurence Harvey and Jean Simmons. The third was Two Gentlemen Sharing (1969)—Evan Jones was the writer and we had a very good time making the film and became very good friends. One day he came to me and he said, “Ted, I’ve got this job adapting this Australian book and it’s a fantastic book and it’s right up your alley. You’ll love this book.” He said, “Read it and if you like it I’ll talk to the producers here in London.” I read it and I loved it. It was an American company called Group W Films that was financing the film with Australian partners. A guy called Peter Katz was running it and he hired me. That’s how it all came about.

TS: What was the Australian film industry like at the time? Was it similar to Canada’s or were they more developed?

TK: Yeah, they were slightly more developed than Canada. They had a running film industry. It was still in a very nascent stage. After I did Wake in Fright, a lot of the Australian directors—Bruce Beresford and Peter Weir—all said to me “You really inspired me with that film. You can make great films in Australia.” They all had their eyes on Hollywood but they realized they didn’t have to go to Hollywood. They could make films in Australia. I was very gratified to hear this; I liked the subject of the film a lot, the outback was the most amazing place. No one had ever photographed it, it was a very strange landscape. How anyone could ever live and work there I don’t know….the land would beat you down.

TS: Did you feel there were similarities between Canada and Australia?

TK: Yeah, there was. . . I had been up in Northern Canada and it was the same open spaces. On the surface of it you’d think this would be liberating but it was not liberating—it was imprisoning. It was space that trapped you and imprisoned you and that was the same with the landscape out there in Australia. It was five hundred miles in every direction. It was nothing. I used to describe Canada as “Australia on the rocks.”

TS: Being an Albertan, I found a lot that was familiar in the film.

TK: Yes, the hyper-masculine society. The macho way of life.

“What do they do for human contact?” and he said, “They fight.”

TS: Where do you think this hyper-masculine society comes from?

TK: Listen, when I landed in Australia—you know how you find out about a strange place, a strange country? You know how you do it? You take the editor of the local newspaper out to dinner. He knows everything. He knows where all the bodies have been buried. He knows what’s going on, what’s happened in the past, and what’s going to happen. He was the one that told me—this is in the town of Broken Hill, a mining town, the only people there are miners—and he said to me, “Ted, you do know that in this town the men outnumber the women three to one.” Think about it, my friends. I said, “Three to one? Where are the brothels?” He said, “There are no brothels.” I say, “Well, is there a lot of homosexuality?” He said, “In Australia? Are you kidding me? Absolutely not.” I said, “What do they do for human contact?” and he said, “They fight.”

And of course I put a scene like that in the film, after the kangaroo hunt, when the three men are rolling around on the ground, the doctor and the two others. They’re all wrapped around each other. Although they’re fighting, they’re also embracing simultaneously. Everyone there wanted to fight me because I looked like a sixties hippie with my long hair to the middle of my back and my droopy handlebar moustache. They would stick their jaws out and they wanted to fight me. These Australian guys would put their chins out and I’d think, “They don’t want to hit me. They want me to hit them.”

This was in line with what the newspaper editor had said. Broken Hill is a mining town. There is nothing else there. They’re all miners. There are no women. Women are a civilizing factor in life. Women were not allowed in the bars and the pubs. They were not allowed. And then you were living in a town surrounded by 500 miles of nothing in every direction. Of course it’s imprisoning! What are you going to do? Go out into the desert in the dust and the heat. There’s nothing there! There’s nothing! You’re trapped! It was just like prison. You can’t get out of there! The cities, Melbourne and Adelaide, were over 300 miles south. There was nothing between there and them, maybe the odd kangaroo.

TS: So the hyper-masculinity was a result of industry?

TK: Maybe it sounds like a pathology. It’s not. There was nothing else to do.

TS: Do you feel colonization played a role in this behavior?

TK: I think so. I think so. There were a lot of Irish immigrants there. They were all second and third generations immigrants though. The similarity with Canada was the same kind of loneliness and vast spaces and lack of women. I went to Hudson’s Bay and there was nothing there. You’re stuck in this town and around you is 100 miles of nothing. In Canada, it was forests and things but you were totally isolated. So it was very similar.

In Broken Hill, the workers were paid very well. There was zinc mining and there were sheep ranchers on the edge of town as well. But after that there was just nothing. You see the railway line disappear perspectively—I established that in the very first shot of the film. How would you like to be teaching at that school? Pan around, absolutely sweet fanny adams. Nothing. I make that statement in the very first shot.

TS: Do you think that the behavior in the bars, the macho posturing, was borne out of an inferiority complex?

TK: I find it hard to explain except that it was a totally masculine society. Women civilize us, otherwise we’re brutes. I don’t think there was a movie house in Broken Hill. There’s nothing to do there except be an aggressive man. That’s what made it interesting to me. Imagine being a schoolteacher from Sydney. The teachers there had to teach three years in the outback before they could get their teaching license to teach in the big cities. And you had to post a bond of a thousand dollars to make sure you stayed out there. If you came back mid-term you lost a thousand dollars. That was a lot of money then, it’s a lot of money now. The whole subject of the picture is this guy that can’t stand the ethos of this hyper-masculine society around him.

In D.H. Lawrence’s novel Kangaroo he describes it perfectly. He says you’re totally by yourself in this vast emptiness and you think the landscape is watching you. And that was often the case. When I was by myself, looking around for locations and things, I’d feel someone was watching me. I’d snap my head around and of course it was just more emptiness. When I read Kangaroo, I said, yes, that’s absolutely right. You feel that landscape is a giant being who is inimical to human beings and doesn’t want you there. These are the kinds of thoughts that cross your head in this kind of landscape. It’s totally unreal out there: the ground is orange, the trees have blue leaves, some of the plants are purple. I mean, it’s totally unreal. It’s like you’re on another planet.

TS: Were you ever inspired to make a similar film in Canada?

TK: I never did. Although First Blood, which I shot in British Columbia, up in the wilds of northern British Columbia, had similar elements. I did look for another film to do in Australia though. I found it so interesting. But I didn’t manage to find anything as good as Wake in Fright.

TS: What was the budget for Wake in Fright?

TK: It wasn’t very much. Somewhere around a million dollars. I made it for very little money.

TS: What were the circumstances that allowed you to make it so successfully with such a limited budget?

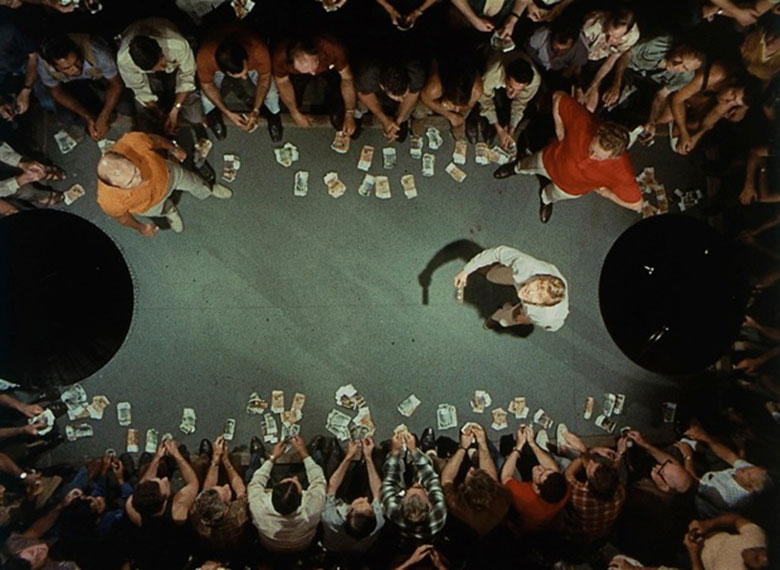

TK: I loved the Australian crews. They were young, enthusiastic. They didn’t have strict responsibilities. An electrician would move furniture and a prop man would move a light. In Hollywood an electrician would never touch a piece of furniture. They were all enthusiastic. They all worked hard. I had a great time with them. The subject was so good, the book was so good, we had a great script from Evan Jones, we had a great cast. Australians are natural extroverts. They are. They’re very outgoing. I was able to channel that energy into terrific performances. For example, the Two-Up game. All the people in that sequence were people I gambled with. I had nothing to do on Saturday nights so I used to go to Broken Hill and that was the form of entertainment. We used to play Two-Up there. When I was shooting in Sydney, I went to a Two-Up school. All those guys in the Two-Up sequence are all the gamblers I played with in Sydney. They were all real people. They weren’t actors. They had a tremendous amount of extroverted energy which I was able to channel into terrific performances.

TS: It feels very authentic.

TK: I did have Jack Thompson who was a terrific actor and became a minor star. He worked in Hollywood and was in some terrific films. He’s a terrific actor.

TS: When it was released, did it attract any attention in Canada?

TK: It was shown at TIFF, very successfully, but I don’t think it ever got a proper release. United Artists, who were distributing the film, didn’t think the film would have any appeal to America and they had the Canadian rights as well. When it failed in New York—it got tremendous reviews in New York—but they opened it on a Sunday night, in a small cinema, in the east end of New York, during a snowstorm… Nobody came. They said, “Kotcheff, you see? We told you no one would come.” I said, “Oh, you bastards, you love self-fulfilling prophecies.” They never advertised it and opened it under the most inhospitable circumstances… I don’t remember it being released in Canada. After it failed in New York financially, it became worthless, as far as they were concerned.

TS: Subsequently has it received any attention from Canada?

TK: No, it’s more appreciated in Britain and France and the United States. It was re-released by an American horror film distributor. But I don’t think aside from appearing at TIFF it ever got a wide distribution.

TS: Would it have been possible to make a similar film in Canada at the time?

TK: It was impossible. There was no film industry.

TS: Even in 1971?

TK: The CFDC, the Canadian Film Development Corporation, was created in ’73 I think. I was trying to make The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz as a Hollywood film because there was no Canadian film industry. It had to be made in Hollywood. I couldn’t find the financing because of the Jewish subject matter and because people thought of Canada as being parochial. But then the CFDC was created under Michael Spencer, who just died recently. I sent Michael Spencer the script and he loved it and he put up half the money!

TS: So that was one of the first films that the CFDC funded?

TK: Yes. And I came back from Canada to England to make it.

After it failed in New York financially, it became worthless, as far as they were concerned.

TS: Did you stay in Canada long at that point?

TK: What happened was, the film was made for $900,000. It was budgeted for $750,000 and we went over. The picture came out and won the Golden Bear at the Berlin film festival. When it came out in Canada it made its money back in the first two weeks, Paramount distributed it in the United States. The film not only got great reviews but it made its money back and made profits. I thought I was all set here in Canada—I made a film that got great reviews and made money! I thought everyone would be chasing me with their money saying, “Please, please, take it from me!” Right after that, I adapted St. Urbain’s Horseman, also by Mordecai Richler, and do you think I could get the money for it? Couldn’t get any money. And I had been paid practically nothing for The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. I had a wife and two kids. My fee was $25,000—I had spent that before I finished working on the film! I was broke. I spent a whole year trying to find the money for St. Urbain’s Horseman. I got pissed off finally, I said, “Canada…” I was really angry at Canada at this point. People are so lacking in that American buccaneering spirit in Canada. And then I got an offer to do a film in Hollywood, Fun with Dick and Jane (1977) with Jane Fonda and George Segal. I spent a year trying to fund St. Urbain’s Horseman and I couldn’t fund it and I was living on borrowed money. That’s why I went to Hollywood. I always came back to Canada. I made Hollywood films like First Blood with Sylvester Stallone. It was an American film but I shot it in British Columbia, I don’t know if people know that or not. I shot it in Hope, B.C. Or—as I used to call it—“No Hope,” British Columbia. It was a great setting up there for the picture. It was all shot up there. I tried to work up there as much as possible. I’m a Canadian. I love Canada. I’ll always be a Canadian. But it was very disappointing for me that I couldn’t make St. Urbain’s Horseman after The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz.

TS: Wake in Fright has been described as a horror film or a sort of horror-western. Was your approach to make it as a genre film?

TK: No, I don’t think like that. I don’t think in terms of genre. I wanted to make a good film about an outsider stuck in a hyper-masculine society. One thing that attracted me to Wake in Fright and The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz is that I seem to be attracted to characters that don’t know themselves. In the course of the films they discover things they didn’t know existed. The teacher in Wake in Fright discovers there is a ‘yahoo’ side of him. It humanized him because he had total contempt for people out there. That was the film I wanted to make. I didn’t think it was a genre film, I thought it was a film about a man discovering his humanity, discovering what he was really like. That was what attracted me to it. And also this incredible environment which no one had ever really photographed before or used it as a setting. I wanted to make a realistic film and a moving film about this teacher. Critics talk about genre, I don’t. I don’t think that way.

TS: What are your hopes for the legacy of Wake in Fright?

TK: I made that film in 1971. It came out in ’71. The film has an incredible life. It will not lie down and die. It’s always being shown in festivals. It’s always being re-released. It was re-released three years ago in Great Britain. It was re-released two years ago in France. France loved that film, when it originally came out in ’71. The only country it was successful in was France—they love stories of men under existential stress. Two years ago it was declared a “Cannes Classic.” It’s one of only two films that have been screened twice at Cannes: one was Antonioni’s L’Avventura and the other was Wake in Fright. It went to Cannes in ’71 and two years ago it screened again. It seems to have an endless life. It’s very gratifying for a director to have a film that will not go away and die . . . You feel like the film has become a classic.