Janus, the ancient Roman god, is depicted with two faces: one looking to the future, and one to the past. Tasman Richardson’s Janus does the same.

Straddling the left and right brain, Richardson’s dual-channel video installation, launched February 2nd at EMMEDIA’s PARTICLE + WAVE Media Arts Festival, is an astute interrogation of video-as-medium and, I wager, an abstract gesture toward the looming precipice upon which our contemporary Western culture seems perched. Drawing viewers into an encounter with the eponymous two-faced god of transitions and gateways, Janus contemplates nostalgia—that peculiar projection of the past into the present—and its potential to offer a way forward.

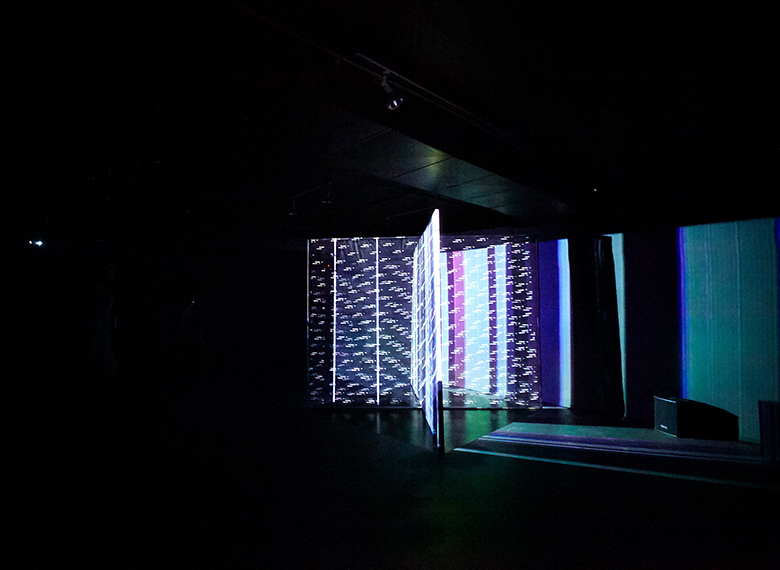

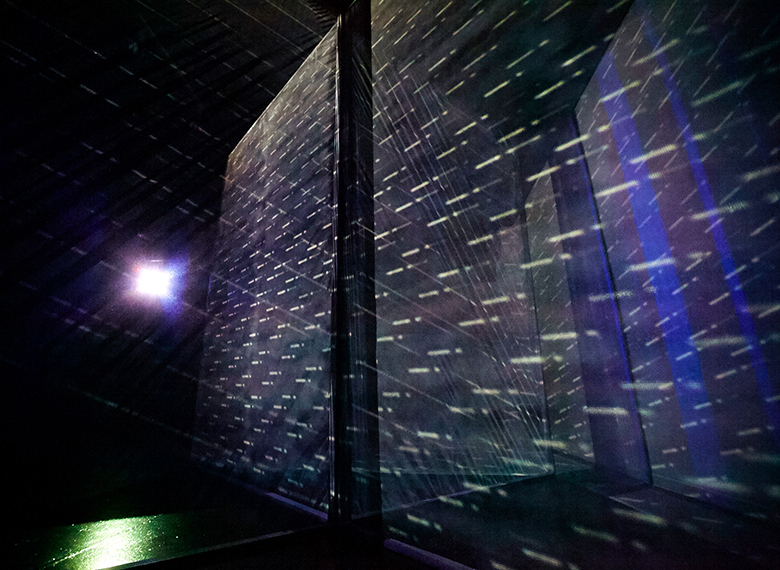

Projected on screens that intersect to form a symmetrical X, Janus studies the decaying electrical current flowing through an ’80s-era Atari 2600 game console in two channels. One video channel explores a concrete audiovisual composition, singing in the vibrant colour and melody of 8-bit video games, harkening to the aesthetic of chiptunes and glitch. The second channel explores the darker, more rhythmic monotone noise textures that emerge from the same source, a nod to nightmares and unconscious impulses. Simultaneously complementary and converse, the two creations reckon with the two-faced god of failure and passages.

"The pendulum swings from realism to abstraction in history, and in my own continuum, it's the same," Richardson reflects on the trajectory of his work. By subjecting Atari 2600 game consoles to controlled brownouts, Richardson produces randomized audiovisual glitches as output—random signals bursting through in a fury of sound and colour, tone and vision. Repeated Atari console failures are recorded, categorized, organized, repacked. Drawing from a library of these random, generative elements—new and unauthored except by the machine and chaos—Richardson’s pendulum inverts the cultural dictionary he initially proposed in the late ’90s, the Jawa Manifesto.

Eschewing simulated realities, and narrative or figurative content, Richardson's pioneering of the Jawa style took video sampling to an extreme.

A video editing technique named for the scavengers of the desert of Planet Tatooine in Star Wars, Jawa is: “Those scavengers of modern myth, stealing and salvaging technology and remodelling it for their own purposes. Nomadic pirates of the alien wasteland.”1Eschewing simulated realities, and narrative or figurative content, Richardson's pioneering of the Jawa style took video sampling to an extreme, “stealing and salvaging technology,” treating the presence of sound and image as a single concrete unit. He and I chatted about the work, and he said, "It's static and very related to the cut up or collage. Dead materials, reworked into new but essentially static or dead compositions that are identical with repeated screenings." Studio-based edits become the notes for an audiovisual score, the results of which can be performed to an extent, but ultimately the result is always a kind of playback.

A combination of his once-sidelining Atari experimentations and his now-established Jawa technique, Janus stands as a new and more unpredictable manifestation of the artist’s intent to create languages of sight/sound. Richardson sees video as a concrete audiovisual unit for composition, notes for a score. Describing his motivation behind this, he says:

There are two practices I'm reacting to. The first is the proliferation of what I'd call 'death culture.' There's so much to be said of death culture, both in industry and manufacturing, but also in the media arts. The second reaction was to the endless pursuit of greater and greater realism [in video] in the form of higher frame rates and resolutions. I once said that the lens defines space, the recording defines time. I see this attempt to simulate reality with greater accuracy as overlooking the existing biological experience of simply living, which is itself, the highest resolution and frame rate imaginable, with the greatest immersion possible.

As an evolution—or inversion—of appropriative video editing in Richardson’s early work, Janus meditates on the medium of video as something that doesn’t need to simulate life—there is life already inherently in the medium, a life revealed when all vestiges of figurative or representative content are stripped away. Born out of a sideline of Atari 2600 experiments, Janus is a kind of end-run around video as we traditionally think of it. Not wholly dissimilar from the way that Rothko or Pollock re-examined what it is to paint, Richardson seeks to reveal the true nature of the (video) signal, the ghost in the machine.

Something at once nostalgic and futuristic, Janus is video blasted free of the dead flesh of the figurative, a unique style of audiovisual composition where both visual and auditory elements emerge from a single source—the electronic signal. Perched on the precipice, regarding mainstream Western culture, our necrotic preoccupation with narcissistic documentation—from Facebook Live to Snapchat lenses—Janus points to a potential future where video is not a recording but an expression of pure signal. A future where two machines will sing beautiful duets in Atari tones.

Janus was presented at EMMEDIA’s PARTICLE + WAVE Media Arts Festival, and is showing February 3-25th, 2017.