If I close my eyes, I can still see the crumbling old villa resting, as if asleep, in the heat. The air is honey-sweet and dusty with the scents of lavender, rosemary, and unfamiliar flowers. I stand in the shadow of the cypress trees that line the ancient driveway, long reclaimed by weeds. Faint lines remain where car wheels, or perhaps wagon wheels once rolled, and a heavy, rusted chain is looped between two posts at the end of the road.

Artist, novelist, puppeteer, filmmaker, and friend, Lorenza Mazzetti has spent her lifetime being creative, telling stories, being part of history and making history. Now 91, she lives in Rome with her twin sister, Paola, also an artist and a practicing psychotherapist. Their tiny apartment is a dream-like jumble of paintings, books, and, quite often, people. (It’s nothing, as I found out early in our friendship, to be at their place on a Tuesday for a casual dinner party for 18. And again, the next night. And the next.)

Despite a childhood punctuated by war and murder, Lorenza has had major exhibitions of paintings in Israel, France, and Germany. In the 1950s, she co-founded Free Cinema, a film movement that won her an award at Cannes and influenced top filmmakers from around the world. Her first novel, Il cielo cade (The Sky Falls) won the Italian literary Viareggio Prize in 1962, and was turned into a film starring Isabella Rossellini in 2000. In 2014, she released her memoirs, Diario Londinese (London Diary), about her time in England in the 1950s; it's set to be released in English this year. And in 2016, a documentary of her life, Perché sono un genio!/Because I am a Genius!, was screened throughout Europe. Every year since I have known her, I have witnessed as more and more people pay attention to her work, her history, and her role as a creative. “It appears I have become something of a legend,” she told my partner on a recent visit, and then laughed.

My first glimpse of Lorenza was at her apartment in Rome. She was—is—tiny, and at the time, dressed in a well-worn plaid shirt, oversized green pants, and orange plastic sandals.

But it took an unplanned visit to a deserted villa in Tuscany two decades ago for my family and I to meet her. My first trip to Italy, I wanted to do everything, and we tried—even biking through the Tuscan countryside. On that ride, the guide took us to an old country cemetery. A towering glittery monument stood in part of the cemetery, homage to one Roberto Einstein and his family. Einstein, our guide explained, was a first cousin to Albert Einstein. The two had grown up together. But toward the end of the Second World War, when the Germans were retreating from Italy, Roberto’s family was murdered, shot in their villa on August 3, 1944. The only survivors, our guide recalled, were little girls. Twins.

After we returned home to Canada, I couldn’t stop thinking about those girls. I had so many questions. Twenty years ago, there wasn’t much to be found, but I’d comb the Internet—library archives, newspapers, and academic papers—searching for information. One night I came across a story by Corrado Farina, a renowned Italian writer whose email address was at the end of the story. I contacted him and a few days later, he sent a friendly note—and Lorenza’s contact information. I wrote her, of course. And one day, a thin white envelope arrived: a letter in spidery handwriting on lined paper torn from a notebook. “Cara Shelley, I will see you when you come to Rome, but please let me know when. I will be happy to prepare for you a dish of spaghetti!” And so, seven years after we first heard the story about Roberto Einstein and his nieces, we returned to Italy.

My first glimpse of Lorenza was at her apartment in Rome. She was—is—tiny, and at the time, dressed in a well-worn plaid shirt, oversized green pants, and orange plastic sandals. “Welcome,” she said. “I am Lorenza. What do you want to know?”

“Everything,” I said.

“Well, then,” she said. “Let’s start.”

In 1902, Roberto Einstein—Lorenza’s uncle—met Cesarina Mazzetti (Nina, to her family and friends.) A few years later, they married. Their own two daughters, Anna Maria and Luce, were born and they moved to a farm near Florence. Not long before the Second World War, Roberto and Nina also became the guardians of Lorenza and Paola Mazzetti, the seven-year-old twin daughters of Nina’s brother, Corrato, whose mother had died giving birth to them. “My father, he did not know what to do with two little girls,” Lorenza told me.

Life was good, even though they heard rumblings from Roberto’s family and friends in Germany. Life was not so good over there, and hadn’t been for years. Roberto’s cousin, Albert, had fled the country a few years earlier, and his German property was seized and his books burned in 1933. Like Roberto, Albert was Jewish and he had become a symbol for the Germans of what they hated about Jews, intellectuals, the bourgeoisie.

The Second World War came. Roberto’s wife and daughters were murdered and the farm's villa was set on fire. Lorenza and Paola, spared because of their last name and religion, were locked in a room while the Germans killed their cousins and aunt. Roberto, who had hidden in the hills, took his own life a year later, when he couldn't bring his family's murderers to justice. The two girls were left in the care of their tutor. But a short time after that, he deserted the twins, claiming there was no money left in the estate. Almost everything they had inherited was gone: land, money, art. And their family, too. “I laugh now, but it’s a terrible story,” Lorenza said. She has only ever talked about this part of her life once with me.

Almost everything they had inherited was gone: land, money, art. And their family, too.

There wasn’t much work for a young woman in post-war Italy. Lorenza headed to England after hearing that she could pick potatoes there. She was hired, but the first time a fellow worker tried to load a 100-pound sack of potatoes on her back, she fell over. It would have weighed more than she did. Eventually she found work as a barista in a coffee shop in London. A photograph from that time shows her behind the bar, making espresso. She wasn’t good at making coffee, she claims. Her heart was elsewhere. But it provided her with money to buy art supplies and helped her make friends in London. Only then could she think about what she wanted to do next. And what she wanted to do was make art, something she and her sister had been doing since they were small. That decision led her to the Slade School of Fine Art in 1951, the day before the new fall semester was to start.

The woman at the admissions desk, however, refused to consider the idea. “It’s too late to start this year. There are all these documents to fill out; you need a portfolio,” she told Lorenza. “Come back next year.”

“Next year, I will be dead,” Lorenza recalls telling the woman. “I started screaming, ‘I want to talk to the director!’” The woman summoned a man to escort Lorenza to the exit. But he looked at her work. “Come tomorrow morning at 9 a.m.,” he said. “Do not be late.” He was, of course, the director and realist painter William Coldstream.

“Of course, I fell in love with him a little bit,” she confessed to me with a chuckle, “But the next morning, I am late. I run. I collide with the director. I drop everything I have.” She was upset. She thought he would kick her out but no—he laughed. He helped her gather her things. It was a good start. For the next couple of years, she went to school two days a week from 1951 to 1952; her name is still listed in Slade’s records. The rest of the time, she made coffee and art. Her instructors included Graham Sutherland (famous for his now-destroyed controversial portrait of Winston Churchill), and Lucien Freud (well-known representational painter and grandson of Sigmund Freud).

In time, she heard that the school had a film society. She didn’t tell her professors, but she had decided to make movies. The first one, entitled K (1952-53), would be an adaptation of Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis. Kafka’s novel, first published in 1915, tells the story of a young travelling salesman who wakes up one morning to discover he has been transformed into a cockroach. Since the 1950s, there have been several movie adaptations of the story, but in post-war England, Lorenza’s idea to turn The Metamorphosis into a movie was brave, fresh and shocking. So was the fact that she had been doing it with Slade equipment and supplies. Coldstream found out and threatened to expel her.

“But film is just a different form of art,” she argued. He either agreed or he believed her; at any rate, he offered to show her film to his friend, Denis Forman, the director of the British Film Institute. Forman was so impressed that he offered her money from the institute’s Experimental Film Fund. It was 1954. She could continue making films.

"She was a very respectable, responsible person, certainly not a thief," says actor Malcolm McDowell in the documentary, Perché sono un genio!/Because I am a Genius! "If you're a young filmmaker, you get films started any way you can."

“No film can be too personal. The image speaks. Sound amplifies and comments. Size is irrelevant. Perfection is not an aim. An attitude means a style. A style means an attitude.”

She filmed Together (1956), her story of two deaf mutes, dock-workers in East London. They are friends boarding with a family that doesn’t want or like them. Every day, as the pair walks to and from work, they are taunted by a group of children. There is no dialogue and no set, no fancy lights and no special effects; everything happens in and around East London. As actors, she relied on two friends, Michael Andrews and Eduardo Paolozzi. Like Lorenza, Eduardo had his own fair share of heartbreak. And he was to become one of the most famous artists of the 20th Century. But in the 1950s, he was simply Eduardo, one of the many creative people that floated—still float—in and out of Lorenza’s life.

Denis Horne, her lover at the time, helped write the screenplay for Together, based on her short story, and because of that, she insisted on naming him as a co-director. But they didn’t agree on anything else, she says. He wanted words. She needed silence for her story to be told. It later came out that he did little but help her work through her own ideas. “We argued a lot,” she told me. “I finished the film alone. Denis couldn’t accept that I was becoming more famous than him.” Horne dropped out of the picture and Lorenza edited the film without him, in a house that the British Film Institute owned in the English countryside. Then she returned to London.

The idea behind Free Cinema became official in February 1956, one month after Lorenza finished making Together. She was heartbroken, but she still had her friends, a colourful group that included Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson. “Every night we would go to Lindsay’s apartment,” she said. “He was a good cook. We would eat and then he would play Irish folk songs, the songs of the children.” They would sing, laugh, stay up late and talk about art and film.

One night, the quartet of young filmmakers—Lorenza, Anderson, Reisz, and Richardson—got together at the Kitchen Soup Cafe on Charing Cross Road, where Lorenza worked. They talked about what their films had in common. They talked about how it was time for a change in British film and how the world needed what they had to offer. And there, on the cafe table, they wrote their manifesto, pledging to produce innovative, ambitious, and creative cinema. “No film can be too personal. The image speaks. Sound amplifies and comments. Size is irrelevant. Perfection is not an aim. An attitude means a style. A style means an attitude.”

Free Cinema became the program name for the screening of three of their short films that same month at the National Film Institute. And what was free? They were all operating outside the mainstream film industry, so they were “free” to do as they liked. The screening was a huge hit, and for these four young filmmakers, life was suddenly golden. People wanted to know them, to see their films, and find out what they were doing next. They became the next big thing in a city full of big things.

And there, on the cafe table, they wrote their manifesto, pledging to produce innovative, ambitious, and creative cinema.

A Free Cinema box set was released in 2007 by Facets Multi-media in Chicago. It contains Lorenza’s film and others, plus a documentary about Free Cinema’s rise and fall. I brought it to Lorenza once, in hopes that we could watch it together, but she took one look at the cover and threw it back at me—her name was only mentioned on the booklet inside the box. “All four of us, we were equal,” she said. “We formed Free Cinema together.”

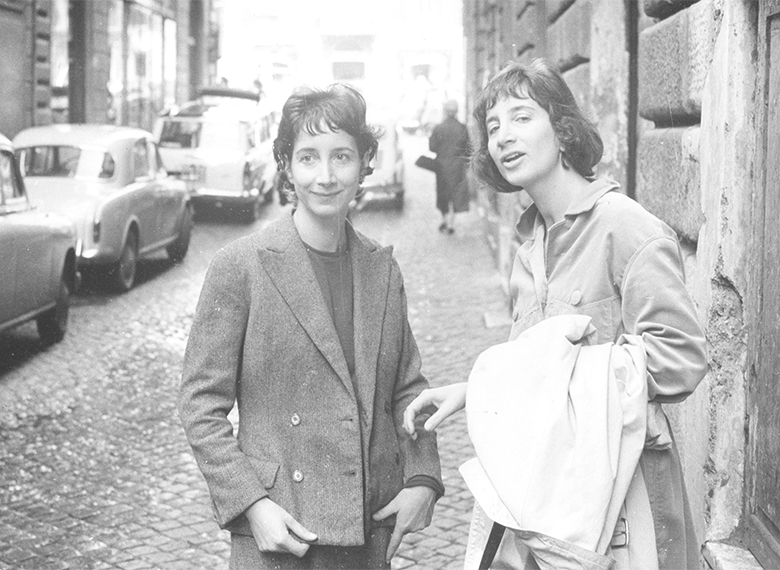

For Lorenza, that time in her life was filled with great creativity and happiness. That spring, Together was chosen to represent the United Kingdom at the Cannes Film Festival in France. It wins a major award, special distinction in the category of short film. It was one big party, day after day, she recalls. A photo shows Lorenza, a pretty, dark-haired woman, wearing a simple, sleeveless shift with a loose bow at the waist. "I made my own dress, she told me. Somehow I am not surprised.

Back in England during that time, Free Cinema's program boundaries at the British Film Institute quickly expanded to include the likes of Francois Truffaut and Roman Polanski. But by 1959, those young filmmakers were moving on. Free Cinema ended on March 22, 1959, with another public statement from the quartet:

Now this is the sixth of these programmes. It is also the last. We have decided that this movement, under this name, has served its purpose. So this is the last FREE CINEMA . . .

FREE CINEMA is dead. Long live FREE CINEMA! . . .

The strain of making film in this way, outside the system, is enormous, and cannot be supported indefinitely. It is not just a question of finding the money. Each time, when the films have been made, there is the same battle to be fought, for the right to show our work. As the madman said as he hit his head against the brick wall, ‘It is nice when you stop.’1

Lorenza returned to Italy, but her struggle to make film was only just beginning. The Italian industry didn’t know what to do with her, she told me. Her film may have been fêted at Cannes, but she hadn’t been traditionally trained, and she was a woman. So why did she go back? She looked at me, puzzled. The answer was obvious, “It is home.”

Paola was there, too, with her daughter, Eva, now a photographer. The first time I met Paola, highly accomplished in her own right, she asked me why I wanted to meet Lorenza. What did I hope to learn? “I don’t know,” I said. “I just had to know.” I want others to know, too, about the tiny dark-haired twins with the sad eyes. This brave and brilliant woman, who was fêted at Cannes. I want people to remember. And beyond just their exceptional history, I think of Lorenza and Paola, and how they have always, always, found ways to create and be creative. To make sense of their lives—the joy and heartbreak—through art in its many forms.

One of the last times we met at their apartment in Rome, Lorenza showed me a photo: her Aunt Nina with all the girls gathered around her by a fence in the country. It is a black and white photo from another world, one where the dark clouds are distant. “If I listen, sometimes, I can still hear my aunt calling us,” she said. “She would say our names, as if they were one. ‘Paol-e-Lori,’ she would call. ‘Paol-e-Lori.’” She fell quiet, still listening.

And now, I am listening, too.