Both fierce advocates for the revival of handmade and experimental film techniques, Kevin Rice and Lindsay McIntyre have kept in conversation for several years about their respective practices and endeavours as film artists and collective members. Kevin Rice is an experimental photochemist and co-founder of the non-profit traveling film outreach organization, Process Reversal (PR); Lindsay McIntyre is an award-winning experimental film artist and former member of The Double Negative Collective, working with handmade emulsion, light play, animation, celluloid manipulation, and projection performance.

Luma asked Rice and McIntyre to interview each other about what it is they do and why it is crucial now.

KEVIN RICE: Based on your experience with Double Negative, what do you think is the most critical function that a film collective serves, both for the individual filmmaker as well as the community in general?

LINDSAY MCINTYRE: Joining the Double Negative collective was an important part of my development as an artist. Having landed in Montreal from Edmonton in 2003, the most important thing for me was to find a community of like-minded artists. Besides my interest in teaching film, it was really the driving force behind the move to Montreal because I couldn’t find it in Edmonton at the time. I thought I would find community at Concordia while pursuing an MFA in film but things weren’t structured like that. I had to look outside of that environment, and as it happens, Double Negative was just a year or so old at the time. The collective itself came out of an impetus from an experimental film class at Concordia a few years prior, so the connections to the school were already in place.

One part of the collective is the space itself—the studio; it’s a film-positive place, a late-night film-friendly refuge, a place to try and fail and rip things up and not answer to anyone but myself. A place that feels creative, where everything you need is accessible, or where the inspiration to create is always present. Another part of the collective is that the members were and still are sometimes a sounding board, a collective-confidant, a support network, but also a critical voice—never afraid to question or push things further. And I’d also say that an essential part of it—at least for the years that I was most involved—was the screenings. It was amazing to find a group of people dedicated to the same obscure images and art forms; people with the same values of experiencing work projected on film, of seeing true artistic expression in the medium of film; people who were willing to roll up their sleeves and make a film screening happen despite having no funding, no support, and no money.

One part of the collective is the space itself—the studio; it’s a film-positive place, a late-night film-friendly refuge, a place to try and fail and rip things up and not answer to anyone but myself.

We would bring in an artist and their work, screen print excellent posters, partner with other groups or organizations to make it happen, borrow chairs from the mission down the street, and basically fly by the seat of our pants. We brought in David Gatten, Guy Sherwin, Nicky Hamlyn, Bruce McClure, and lots of others that way. This was largely due to the vision of collective member Daichi Saito, and later, Malena Szlam. Double Negative, like many of the other film collectives, has a vision, and a dedication to that vision which is an absolutely endlessly inspiring thing. I definitely miss it now that I’m back in Edmonton, but I’m working on building another community.

LM: With Process Reversal you’ve done a lot of touring, traveling, knowledge-sharing, and engagement, which is really quite different than the activities of Double Negative—would you say that those are the most essential parts of your collective?

KR: At the moment, yes, I would say that those are the essential parts of our collective, which is a bit peculiar compared to other collectives. However, the initial desire of Process Reversal was to be something very much similar to what you described for Double Negative. In fact, we also began under similar circumstances: as filmmakers going to the University of Colorado in Boulder together, gradually finding each other through our common interest in photochemical film, as well as a rejection of certain attitudes and ideologies present at our school. In time, we wanted to create a more permanent space for people like ourselves outside the school, a place whereby we could get access to all the equipment and resources we needed to make our films, and have a community of like-minded people to share, discuss, and push the boundaries with. But, unlike your experience, we didn’t have a space and we also didn’t really have a clear strategy for how to achieve one.

Having recently graduated from school, the one thing we didn’t have in particular was money, so naturally, the discussion within our group always became a discussion of finances. Eventually, there was only one way we felt we could approach the problem; if we were to expect money for a space (from grants, donors, members, etc.), we had to first generate a history as an organization. And so with that in mind, we each went out into the world by the seat of our pants, trying to seek out any and all opportunities to make a name for Process Reversal—through screenings, workshops, engagement, etc.

I think that we eventually warmed to the idea of being an organization whose mission was more than just making a space for ourselves, but instead helping the global community achieve and sustain film as an artistic medium.

It was during this time that we inadvertently became this nomadic organization, which I’m mostly to blame for. The year prior, I was able to travel and meet many of the amazing groups in Europe by simply writing an email, sharing some work, and arranging a workshop with them, and I wanted to do the same thing here in the US. Now that our collective had a name, I decided to do a tour under that banner which resulted in the first Frenkel Defects. Anyway, over the last four or so years we’ve carried on in that way while our initial dream of a space took a bit of a backseat for a variety of reasons. Perhaps the most important one was that the housing market in Colorado exploded (because of the legalization of marijuana) and it became exponentially difficult to find and afford a space. But also, I think that we eventually warmed to the idea of being an organization whose mission was more than just making a space for ourselves, but instead helping the global community achieve and sustain film as an artistic medium.

Today, our programming still consists of touring workshops and screenings, but it’s also taken a shift towards more local outreach in Colorado where most of the members are still based. For example, we began a screening series in Denver (called Process Reversal Presents) to try and bring filmmakers there, and we also hope to start an experimental film section in association with the local film festival. Simultaneously, other members are working hard to establish educational programs for both youths as well as the refugee population in the Denver metro area.

In the future, we're hoping that these efforts can provide a base for us to finally realize a space in Colorado, but I think that the touring/knowledge-sharing elements of PR will always remain the prominent aspects of the organization.

KR: Over the last few years, you’ve been conducting interviews and producing footage for your soon-to-be completed newest work, The Story of Film, about the state of analogue film. Can you describe this film, and also your personal view of where we stand with analogue film?

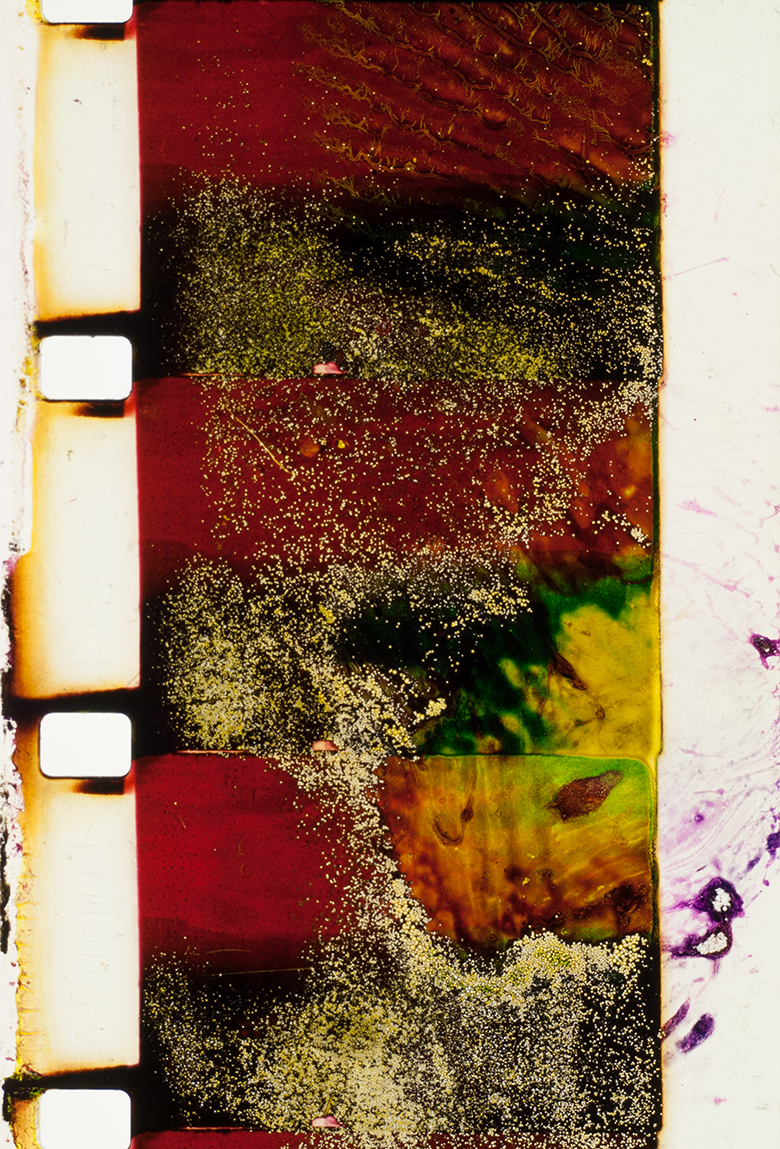

LM: Yes, the film is a bit like a biopic of the life of film and it treats film as though it were human. Film is missing, dead or forgotten in a hospice somewhere at the start. It’s a project that I’ve been working on since 2012 and I’ll be finishing it this year. It’s structured a bit differently than most of my film works in that it deals quite heavily with story and content, so that is a shift for me. It’s also shot on or transferred onto 16mm film that has been coated with a handmade silver gelatin emulsion and it’s partly made up of found or archival 16mm film, so it’s very labour intensive, alive, and sometimes volatile.

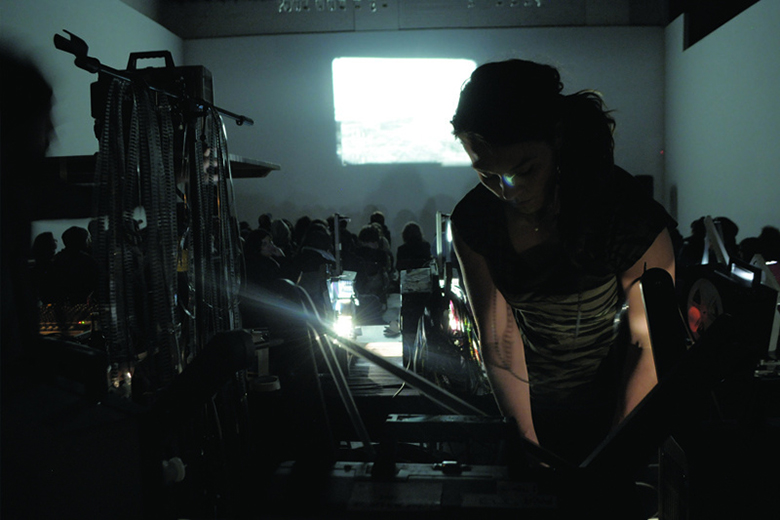

It includes interviews with people from all facets of film—from the industry side and from the artist-run side of things. It documents, in a slightly unconventional way, the history of celluloid-based film from its birth, to men in white lab coats in a dark room 150 years ago, to what’s considered its imminent death as an industrial tool, and beyond. It’s what’s beyond that most interests me; it’s what’s happening now. Film, now that everyone thinks it’s dead or dying, has been freed from all the prior notions of perfection and documentation, rigid commercial expectations, and aesthetic conventions; now it can truly become an art form. Too often people think of film simply as an acquisition format, another version of digital or video, but it’s far from another version of the same thing. It does things that no other medium can do. I think it would be sad and ridiculous for industry to reject film as a medium, but at the same time, it opens up a whole new way of thinking for the medium that leaves so much room for exploration, so I find it very exciting. I don’t think that’s a new idea for many artists working with film, but it might come as a surprise to others. There will always be people producing film stock, but whether it’s commercially manufactured anymore or not, I will always shoot on film. It’s a tactile, physical thing. I can hold it up to the light and physically see the pictures and even the soundtrack; I can physically and chemically manipulate it. I still find it magical in the darkroom, and outside of the darkroom my practice is also heavily connected to the physical apparatus of cinema: the light and dark, the rotating shutter, the mechanics. These are also part of my work when I perform with projectors.

Film, now that everyone thinks it’s dead or dying, has been freed from all the prior notions of perfection and documentation, rigid commercial expectations, and aesthetic conventions; now it can truly become an art form.

My practice has been entwined with celluloid film since the beginning. I practice in a mostly self-sufficient way, from making the emulsion and coating the film, to operating the camera (and sometimes making the camera), editing, and sound. I aim to one day perforate my own base material as well. The great thing now is that other industrial barriers are breaking down and becoming easier for individuals to cross; we can now 3D print prototype parts for old worn out projectors, use a CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machine to cut new components for cameras, and dream up new components to function with newer technologies. The international artist-run labs movement is also a big part of making these practices possible, and the movement is growing. It’s putting the tools in the hands of artists. Reclaiming machines discarded by industry makes these previously largely unexplored tools more accessible to artists who can get to know them intimately and exploit their functions. There are some very exciting things happening in celluloid both abroad and here in Canada in the next few years. It’s a great time to be working with film.

LM: What is it that attracts you to film as a medium, and what are your own thoughts about the status of the medium in the digital age?

KR: Well, that can be a bit of a long explanation. But, I suppose if I were to distil my thoughts, I would say that I’m drawn to film because it’s a perfect reflector. I think it’s capable of reflecting everything within and without, and accordingly, you have no limit to where you can go as a filmmaker. You get to explore places and ideas that have never been explored before. But, most importantly, I believe film to be the most effective device for reflecting the spaces within ourselves. I feel this way because the more and more I discover about the science and mechanism of film—whether it is the emulsion, the film strip, the camera, the projector, the cinema—I find more and more that it is analogous to ourselves: our science, our mechanism and our spirit.

As for my thoughts of film in the digital age, I would just say that film is dead. It was always dead. In fact, that’s probably the first thing we learn about film: that the film strip is just a sequence of inanimate images, and that the only way we are able to see it as a moving image is because of the projector, and a defect in our vision. And so, if it’s a question of how long that illusion will last, then it’s simple really; so long as there are those of us around—who find that we must explore and live within that space—and someone trained to operate the projector, it will continue indefinitely.

KR: Would you say that the style and/or themes of your work have changed or evolved over time? If so, how?

LM: Yes. My work has changed because I have changed. As I evolve as an artist, the concepts and methodologies naturally evolve alongside. I’ve always made things for me, almost in a cathartic way. I make films because I have to—not because I’m trying to communicate some specific thing to a desired audience. When a spectator has a transformative experience or is really affected by the work, it’s an honour and a privilege to have made it. I have become more and more interested in the mechanics and physical components of a film strip, certainly, but also in the apparatus of cinema - all of those elements have become a more central part of my work. Maybe it’s a rebellion against the concept that we are in a period of ‘post-media’. Thematically, it’s harder for me to say that things have changed but I’d say my approach has definitely changed. I work with less self-consciousness and more conviction. And somehow more patience and less patience at the same time. And certainly, ideas get discarded all the time, whereas others get made and really should have been discarded, but overall the work that I make gradually becomes closer and closer to the truth I was trying to achieve at the start. At least that’s the hope.

LM: I remember you telling me something interesting about film being a physical place for you. Can you explain that?

KR: Part of what I find interesting about a filmstrip is that we tend to think of it as flat, when in fact it has quite a bit of depth to its physical composition. I think in the experimental film community, it’s generally recognized that a filmstrip is sculptural, but that idea is almost exclusively associated with acts like scratching into, or collaging onto, the filmstrip. I had the idea that, because of the way an emulsion is structured and exposed, there should be an inherent dimensional quality to the image itself. To test the theory, I did an experiment; I took some of the film I was working on at the time, threaded it into a film scanner, and—using a half-silvered mirror—lit the film strip straight-on from the scanner lens. The idea was that we almost exclusively look at film from a projected light (i.e. back-lit), but by front-lighting the film the images structure would be revealed. And indeed, the actual silver image did have its own planes and troughs; it was a little silver sculpture, etched into the emulsion. And so, calling a film a moving image is actually a bit of misrepresentation; it’s more like a moving sculpture. And that’s something unique to photochemical film, and perhaps even, reversal film.

I feel this way because the more and more I discover about the science and mechanism of film—whether it is the emulsion, the film strip, the camera, the projector, the cinema—I find more and more that it is analogous to ourselves: our science, our mechanism and our spirit.

Anyway, this little physical space inside the emulsion is fascinating to me not just from a technical standpoint, but because it resonates with other feelings I’ve held about the function of a frame; this is where the idea of a frame being a home came about. At about the same time I was conducting this experiment, I was also working on projects that addressed the meaning of a ‘home movie.’ I was working off the idea that a ‘home’ is not a fixed space because, after all, space is a function of time. Instead,I felt that ‘home’ is related to an ephemeral feeling closely associated with kinks and defects in our own self, things like motifs or colors or textures that evoke a sense of being at home. It’s not a logical feeling at all, and you can gain a sense of being home anywhere, but never somewhere. Anyway, I realized that for myself, these feelings were most often evoked through my own films. Especially Sanctuary (2008). And so, I arrived at the thought that when we make a film, we’re practicing architecture, because we’re building a space that we can occupy; one that is both literal, as I mentioned before, but also one that houses our spirit. But like all spaces, it’s not a fixed thing. It’s always changing in relation to ourselves. And so, we’re always trying to go home, but never arriving there it seems. And eventually, the film runs out.

I think when you mentioned The Story of Film to me, I was able to relate this idea of film as an elusive home architecture to your theme: of film as a dying person. I think you can argue that a synonym for a home is our own bodies, and in that sense, I think this idea holds resonance. I think a filmstrip functions in the same way a body does: it houses a spirit, one which is animated by an unseen mechanism.

LM: I’m really especially interested in this film-lab-in-a-sausage-factory thing you are doing now. Can you tell me more about it?

KR: Certainly. My partner, Nazli Dinçel, and I recently moved to Milwaukee (Wisconsin) to purchase a home. As it turns out, we found the perfect place for both our home and a lab: a mixed-use duplex where the first floor was, up until recently, a famous sausage shop. That kind of space, as you know, is ideal for a film lab because it’s already basically a wet lab equipped with all kinds of different electrical supply and ventilation systems. There’s plenty of work to do on the building still, but once it’s up to speed there will be enough space to do all kinds of things.

The first, and most obvious thing, is a film lab which we plan on outfitting with contact printers and optical printers of all gauges, film editing/neg cutting room, a full darkroom, optical sound recording and release print processing capabilities. We’re also going to have a machine shop on site for building parts to machines, a film archive for films produced at the lab, and perhaps in the future, a cinema. And of course, there will be a kitchen plus a room or two for members/resident artist to come and stay in while they work on their projects.

The space will be, I hope, a project under Process Reversal and also be the base of operations for our Frenkel Defects program. It’s a bit early to tell exactly how the space will function, but I expect it would be something akin to L’Abominable. In other words, members will be recruited on a project-by-project basis whereby interested individuals will submit a request to use the facilities for a specific project. We would then review and accept their proposal and train them on equipment specific for that project. After that, they will be a member and have access to the space whenever they need, and there will always be someone on site to help with training as needed.

KR: At the Independent Media Arts Alliance (IMAA) Analogue Film Gathering in Calgary, you participated in a discussion on the issues of inclusion within the film community. This, of course, has always been and remains today a multi-faceted issue for both the commercial side as well as the "experimental" side of our community. As a female filmmaker with an Inuit heritage, do you feel this has affected your work and ability to become a part of this community?

LM: Yes, we had wonderful discussions about all kinds of issues facing analogue artists in Canada today: access to training and tools, preservation and lack of archival space, projection standards and skills, distribution issue, as well as an enlightening discussion on pluralism, equity, and inclusion. Equity and inclusion is a big problem in the media arts in general, but particularly because film has always had close ties to experimentation and the underground, where marginalized voices can actually be heard, it’s particularly important that we, as a community, address the problems created by what can sometimes feel like an elitist art form. Artists have an obligation to take apart structures that are created by conventions. We can’t very well do that from within this pluralist convention. And beyond the perception of the ‘genre’ of experimental filmmaking, how can we be truly inclusive when film is so tied to access to specialized equipment, not to mention the monetary costs associated with film stock itself? The tools need to be accessible to everyone, not just the privileged few. Cecilia Araneda of VUCAVU spoke eloquently about it at the gathering. I’m not sure we came up with any blanket solutions; we probably could have spent the whole gathering addressing this one issue. It’s a really important one. As a female filmmaker with Inuit heritage, I actually don’t feel like I’ve been affected a lot by these issues but that just makes me all the more emboldened to fix them. I think it’s important to champion other voices, and other modes of creation and other stories whether they be Indigenous, female, marginalized, newcomer, outsider, LGBTQ, or barriered in any other way, and I’m excited about finding solutions and hearing those voices.

KR: And, of course, there is no singular answer to the problem of inclusion in our community, but what would you say is the best step that organizations—including film collectives and larger media arts organizations—can take to help ensure a more inclusive environment?

LM: An important first step is realizing that everyone is responsible for inequity—not just those of us that are affected by it. Secondly, I think it’s time to stop being so lazy about it. It is our responsibility as humans to actively do something about this—let alone as artists, co-op or collective members, citizens or neighbors. From the standpoint of a film co-op, we have to stop ignoring the fact that many of these marginalized people don’t walk through the door; it doesn’t matter that the door is open. It is the responsibility of each of us to actively engage and encourage participation. Maybe running workshops in diverse communities will help, or getting outside of the customary ways of doing things and exploding the concept of what film can be (sort of like what Amy Fung did with Images this year), or do it one-on-one, encourage ideas, rethink rules around access and membership, create mentorships, partnerships or programs. It’s also important to remember how important failing is to the process of learning; eventually we will find a way. I think having voices at the table is an important thing, but getting those voices there is part of the problem.