Meet in the Middle: Stations of Migration and Memory Between Art and Film (MITM) is an ambitious multi-year project staging the city of Regina as a meeting place for discourse. The “stations” of its title refer to its programming: a series of films, performances and exhibitions culminating in four days of events and an international symposium, November 2-5th, 2016.

Meet in the Middle uses the central theme of trauma as it relates to migration and memory reflected through film, art and the work located at their intersections. Twinning Saskatchewan with Armenia, the project identifies points of convergence between the two, in their isolated geographies and histories of genocide. Although the fragmentary and durational nature of the project renders it difficult to fully grasp, Meet in the Middle is an impressive testament to the collaborative energy within the city and beyond.

A MUSEUM ON SCREEN

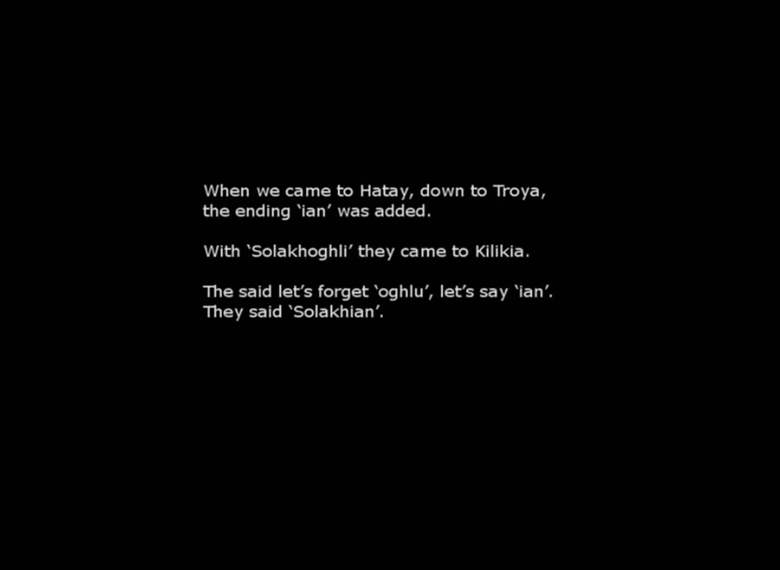

At the centre of MITM’s November events was Egoyan at the MacKenzie—the North American premiere of Steenbecket, an installation by Armenian-Canadian polymath Atom Egoyan first commissioned by Artangel in 2002 and exhibited at London’s now-defunct Museum of Mankind. Creating a contextual framework for this work at the MacKenzie, The Armenian Centre for Contemporary Experimental Art (ACCEA) also presented a selection of films by contemporary Armenian filmmakers at the Regina Film Theatre under MITM’s umbrella. Their series of one-shot, unedited films reflected on the haunting effects of the 1915 Armenian Genocide, contemplating the ways in which the loss of homelands and ancestral presence bears on contemporary experiences. Laureline Koenig and Liza Sargsyan’s layered projection-performance film, Andranik (What’s Next) (2011), illustrated this historical residue with a survivor’s testimony. The speaker—presumably the titular Andranik, delivers a monologue describing the endless iterations of the surname his family was forced to change during centuries of forced territorial and migratory shifts, from the Turkish Surenoghli to Solakhoghli, Solakhian to Tzolakian and then Tzolagian. He selects his final chosen name, Zeytuntsian, so as “not to remember.” This dual act of healing and defiance is weighted down with the film’s weary and anticipatory title, What’s Next? The films variously mapped Armenia’s haunted lands and the connectedness of its inhabitants, reflecting on that which is lost, what is remembered, and what can only be imagined after its traumatic events.

The jewel of the film series was Sergei Parajanov’s resplendent The Color of Pomegranates (1969), selected and introduced by Atom Egoyan. Through a sequence of episodic tableaux, Parajanov composes a poetic biography of eighteenth century Armenian troubadour Sayat-Nova. Each scene, from the trio of glossy, seeping pomegranates that open the film, left impressions indelible, individual illuminated miniatures of the film’s inspiration. Egoyan offered The Colour of Pomegranates as a significant moment in both his cultural and artistic awakenings—“a museum on screen.”

TESTIMONY

The symposium began with an overview of previous stations, launching into an expansive consideration of MITM’s central themes of migration, memory and trauma; discussions lingering on the weight of memory, the role of the artist-historian, and the longing of the diaspora. Artist Mkritch Tonoyan, a former Armenian soldier, discussed his work Roll Call, an audio monument installed at the MacKenzie, in which Tonoyan reads the names of fallen Saskatchewan brothers-in-arms. Rather than recording presence, the work calls out to the dead, looping and repeating their names in a determined gesture of remembrance. The acts of listing and naming were reiterated as favoured artistic strategies, also appearing as motifs in Koenig and Sargsyan’s What’s Next, and Apra Hacopian’s From the World of Silence (2008). Janine Windolph, President of mispon: A Celebration of Indigenous Filmmaking, and Trudy Stewart, mispon Festival Director, discussed cathartic possibilities in relation to their work researching, filming and sharing stories. For Windolph, film functions as a healing tool, through which personal and familial trauma can be addressed (More Questions than Ancestors (2012)). Testimonies, gathered for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission during Windolph and Stewart’s roles as Statement Gatherers for the Saskatchewan region, have also driven their docudrama projects; challenging and making important contributions to the mapping, interpretation and presentation of the broad legacy of residential schools. What is possible to remember through the weight of trauma and time, and indeed if and how the memories of such events can be translated on film are also concerns shared by Atom Egoyan.

Surenoghli to Solakhoghli, Solakhian to Tzolakian and then Tzolagian. He selects his final chosen name, Zeytuntsian, so as “not to remember.”

Memory’s fragmentary nature finds a home in the haunted medium of film. Memory remains, as speaker Dr. Marie-Aude Baronian (University of Amsterdam) noted, the umbrella theme of Atom Egoyan’s multilayered oeuvre. His preoccupation with memory, notably the precariousness of testimony and witnessing in particular, is consistently revisited. Panel speakers traced this line of thought using examples from various films and artistic projects. Presented in her paper “Film, Testimony and Otherness,” Baronian argued that Egoyan’s characters (a term that also includes machines/ screens) are both image-producers and viewers, whose positions can shift into and out of these roles. As viewers, these characters emerge as witnesses with singular experiences. The urgent, singular nature of testimony is bound to various tensions with which Egoyan engages: the profound difficulties in translating horror, the effects of time, the statement as a moment of judgment, dispassionate objectivity vs. emotional subjectivity as they relate to issues of credibility, and all the pressures these tensions produce. So it is in moments of character testimony that the testimonial act and its effects, rather than its content, are significant. The anxiety and infuriation of not being heard or believed is one particularly resonant for the Armenian people, for whom full acknowledgment of the Genocide has been denied.

A COMMUNITY OF WITNESSING

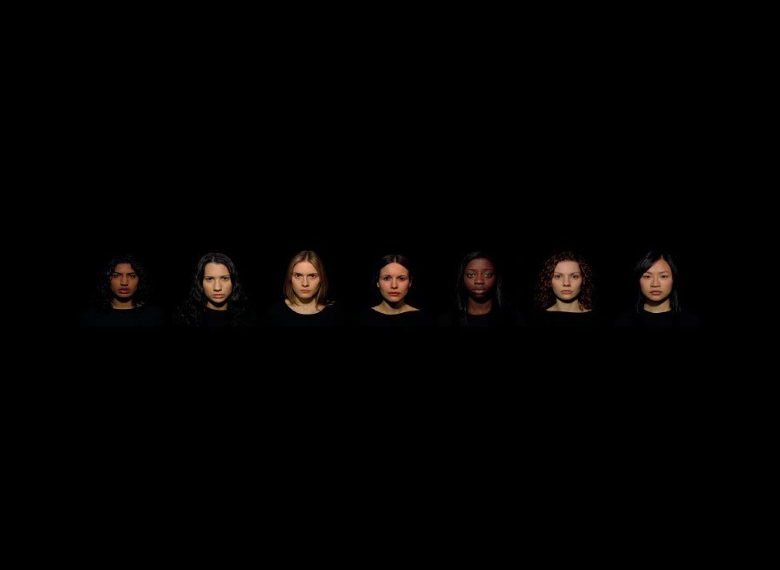

In “Chorus: Positioning the Witness in Atom Egoyan’s Auroras,” Timothy Long (Head Curator, MacKenzie Art Gallery) reflected on Egoyan’s opus on testimony, Auroras (2007). First exhibited at Luminato Festival in 2007, Auroras restages the eyewitness testimony of Aurora Mardiganian, whose distressing account of the death march, kidnapping and genocidal horrors she survived were published in her 1918 book Ravished Armenia. The next year, a film of the same name followed, incredibly, with Mardiganian playing herself. During the film’s promotion, Mardiganian broke down, the toll of repeating her traumatic story having become too much. However, the tour continued, with seven stand-ins assuming her role. This is the thread Auroras picks up, Egoyan’s interest taking root in the process of substitution required to keep the story alive. In a darkened room, seven actresses share a portion of Mardiganian’s story on seven projections that encircle the viewer on three sides, elucidating a moment where Mardiganian is witness to a torturous act, also viewed by the victim’s daughter. Sentence by sentence, the projected women describe the moment the mother is blinded, her face “turned to the stars” while her daughter begs soldiers to spare her. Sight, watching, and witnessing are demonstrated to be at the forefront of this work. Timothy Long, in his presentation, focused on the point at which cinema potently expands into the space of the spectator, the effects of which being an example of theatroclasm, a “destabilising” slip between spectator and art object. Auroras removes the safe distance created by conventional filmic testimony by surrounding, overwhelming, and, with life-size screens, equalising viewers with victims, creating a “community of witnessing.”

Memory’s fragmentary nature finds a home in the haunted medium of film.

In contrast to the isolating condition of the white cube, Egoyan took Auroras further in a modification of the installation outside Berlin’s Maxim Gorki Theater in 2015. Here, double-sided screens depicting pairs of actors were set filed in a row, an arrangement emblematic of a death march. This streetside reconfiguration implicated passers-by, often unwittingly, into the narrative. Viewers could take two positions, passing by the side and watching, or moving in between each screen. This act coerced them into taking the position of soldier, witness or participant. The role of witness takes on particularly affecting significance as Mardiganian’s words declare: “Civilians were more cruel to the deportees along the road than the soldiers.” By casting actors of various ethnicities, Long argues, Egoyan emphasizes that such horrors can affect us all. So too does this management of the viewer’s role(s). In the wake of recent political events, the capacity of each of us to play the role of victim and victimizer takes on the feeling of a particularly topical warning.

THE FLOCK

Egoyan’s refusal to provide resolution underscores the cyclicity, and the repetitive compulsions that characterise and haunt his work. University of Regina Associate Professor Dr. Christine Ramsay’s presentation, “Haunted Geographies in Atom Egoyan’s Calendar and Return to the Flock” discussed this at length, referring to a distinctly emblematic scene from the film Calendar (1993). The film opens and closes with the screen filled edge to edge with a flock of sheep that “never seemed to end.” In the final scene, the voice of Armenian-Canadian actor Arsinée Khanjian’s character floats over these sheep. It is a voicemail she has left for her husband, a photographer played by Egoyan. Over the course of the film, Khanjian’s character, a translator, facilitates her husband’s photographic tour of historical Armenian sites, coming to fall in love, with their guide. The voicemail message recalls seeing the sheep earlier in the narrative, and the moment at which she grips her lover’s hand while watching her husband’s hand grip his camera, filming the endless flock “like you knew what was happening behind you.”

Egoyan emphasizes that such horrors can affect us all.

The film ends with her asking, “Were you there? Are you there?” Given the context of Egoyan’s work, it is not hard to imagine the endless flow as emblematic of death marches and diasporic fleeing and again, the positioning of the witness (“Were you there? Are you there?”). The sheep scene also reaches through cinematic history back toward, unsurprisingly, Parajanov’s Colour of Pomegranates, where Sayat-Nova digs the grave of the holy Catholicos in the floor of his church, one of the many churches also featured in Calendar. Through an open door, a flock of sheep stream in. They steadily fill the church, the place that connects worlds, and surround the Catholicos as he lies in repose. This, and the ritual slaughter of “scapegoats” in Pomegranates, is contextualized in Egoyan’s meditation on Armenian history and legacy of trauma.

VESSELS OF MEMORY

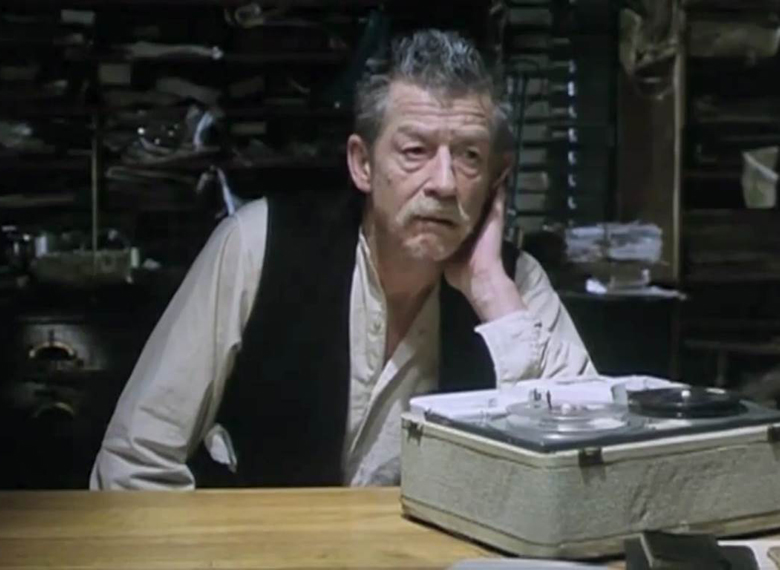

Egoyan’s installation Steenbeckett, the centrepiece of Egoyan at the MacKenzie, expands this preoccupation with memory into new territories. The age of postproduction proves again to be a fertile era, this time in Egoyan’s use of the work of Irish playwright Samuel Beckett. In 2000, he directed Beckett’s one-act play Krapp’s Last Tape, with John Hurt in the title role. In the film, the audience spends one “late evening in the future” with Krapp in his muddled den. It begins with a sigh coddled in unhurried silence on the night of the wearied man’s birthday. In commitment to an annual tradition, he receives and prepares his own dubious gift: an annual slope down memory lane. Groping around for a particular spool, he locates an audio recording he made on his 39th birthday. In this recording, 39-year-old Krapp reviews another tape, made on a birthday a decade previously. Krapp’s feverish excitement melts into brooding despair as he listens to his younger selves in a state of transfixion. He derides the ambition and foolish self-importance of his youth, a “stupid bastard” he barely recognizes. Bitterly, he records a new tape, reviewing the past year he spent “drowned in dreams.” He angrily declares he has nothing to say, save the disappointment of a poorly-received book he published. Krapp desires not simply to archive his memories, but to give them life and meaning in moments of recollection, which the audio recordings are not fully able to fulfill. Both Beckett and Egoyan share an interest in the preservation, transmission, and dislocation of memory and time through audio and video technologies (Calendar, Speaking Parts (1989), Felicia’s Journey (1999)), rituals that also seek to provide protagonists with a sense of identity and personal history. Egoyan skilfully balances Beckett’s minimalism with a fully-fleshed, rich production, in which Hurt’s remarkable voice, the chiaroscuro light, and the talismanic reel-to-reel recorder form a holy trinity.

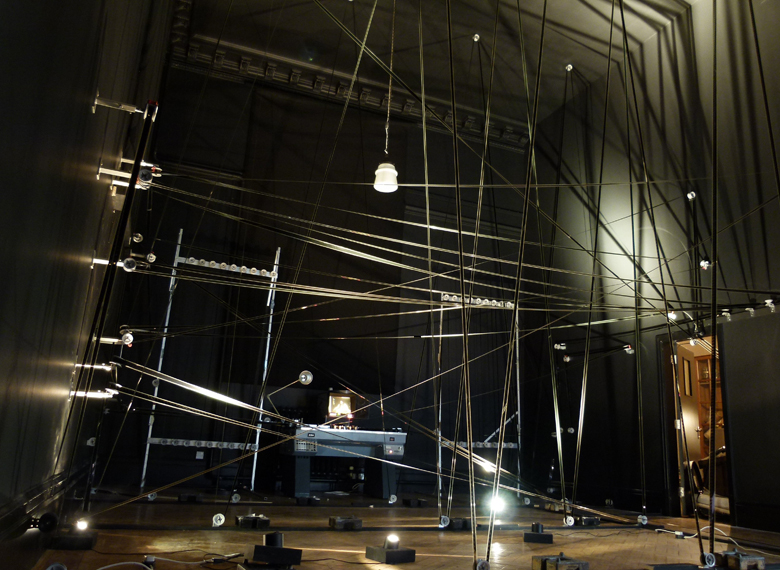

Steenbeckett lingers on the concluding ninth shot of Krapp’s Last Tape, a single takesome twenty minutes long. Offering viewers a close encounter normally contained within film production, the scene’s 35mm strip is liberated from its spool and projector reel, and erected in a kinetic, architectural prism stretching from the gallery’s floor to its ceiling. The endless vein of film (a feat of celluloid!), journeys around the room, punctuated by red leader. It is given motion by a Steenbeck editing table, through which it threads, and which is located behind the film’s latticework, atop which sits a monitor playing out Krapp’s scene. The treatment of the Steenbeck strikes both tender and monumentalising chords. At a safe distance and protected, it is able to exceed its potential, becoming the star of the show. Egoyan reminisces of machines “large enough to hug,” pleasuring in the gentle gestures Krapp performs when handling his precious reel-to-reel.1 In her presentation, Dr. Catherine Fowler (University of Otago, New Zealand), described Steenbeckett as, on the surface, the “scene of a crime”—a space for mourning the death of analogue filmmaking. Indeed, the voluminous celluloid beast is offset by the sleek digital projection of Krapp’s Last Tape on an adjacent wall, an open-casket record of what was and what is. While the 35mm will accumulate dust, and the sound is already linty, the DVD will remain near-perfect. But this is expanded cinema. Here, the subtle absorption of environmental motes is not a sign of degradation but a testament to film’s textural qualities, enduring physical presence and temporality, in which both its power and its vulnerability enjoy equal weight, soaring above and beyond the dominance of supposed “perfection.”

But Steenbeckett works both with and beyond nostalgia, as Dr. Fowler and Dr. David Pike (Chair of the Department of Literature at American University, Washington, DC) argued. Set up as if to compete for our attention, the warmth of film and its curious, near-obsolete technologies prove to be a more commanding presence. Cinema is not guaranteed the cultural primacy it has enjoyed in years past. Pike notes that, in fact, film and digital technology work to reinforce the other. Digital technology may lack the tactility of film, but its efficiency cannot be denied. One suspects that if Steenbeckett suffers a hitch in the course of its run, it will be a more complicated fix than its digital neighbour. Similarly, its archival abilities are more reassuring, a benefit that Egoyan (and perhaps Krapp) would recognize. Pike describes this in terms of a practical and emotional split.

The treatment of the Steenbeck strikes both tender and monumentalizing chords.

Egoyan described the irresistible “confluence of form, content and process” that drew him to cinematize Krapp’s Last Tape, his last film-on-film, and edited with the Steenbeck.2 He described the pleasure of on-screen and real-life transdimensional mirroring, in which Krapp would rewind his tape in tandem with Egoyan’s rewinding of Krapp’s Last Tape. Not only is Krapp deeply attached to his tapes, Beckett’s play is broadly a study on age and the transition of time, a mirroring that can also be found in Steenbeckett. If the medium is indeed the message, in technology we find an extension of ourselves, a shared bodily and psychic decay into obsolescence.

What sets Steenbeckett apart from Egoyan’s other filmic treatises on memory is the shift toward the personal and collective memory-vessel—the physical mediums through which memory is transmitted. The very human necessity to preserve cultural memory has a home made of bricks and mortar. Museums and galleries are our chosen institutional archives of collective memory, although they are not always the most reliable translators. Nonetheless, these archives endeavour to preserve what might otherwise be lost and provide much-needed cultural touchstones, ideas and histories, including those embedded with trauma. Steenbeckett suggests that these institutions are essential to the framing of its own expanded experience, sharing a sense of the sanctity and responsibility of objects and the secrets they keep. These storehouses and machines are the bulky archives of what makes us, keeping what we hold most dear, despite the complexity of this task and the possibilities of failure. And under the rooves of these temples, mausoleums, black boxes and white cubes, cinema expands beyond the screen, allowing audiences to move with fluidity inside the frame into a thinking space, and toward a more embodied, poetic experience of memory and self-reflexivity.

Meet in the Middle is a project by Elizabeth Matheson and Christine Ramsay for Strandline Curatorial Collective and the University of Regina, in association with Timothy Long (Head Curator, MacKenzie Art Gallery) and Rachelle Viader Knowles (Senior Lecturer, Coventry University; and Adjunct Professor, University of Regina).

For full details visit www.egoyanatthemackenzie.ca. A major publication featuring many of the symposium’s contributors, Steenbeckett: Atom Egoyan (Black Dog Publishing Ltd.), will follow in April 2017.