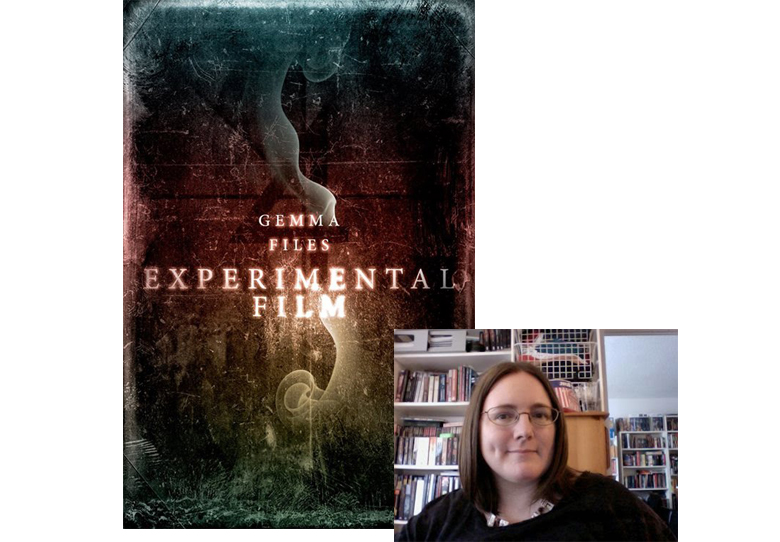

With eight books and countless stories, essays and reviews to her name, Toronto-based writer and film instructor Gemma Files has long been a fixture of the Canadian horror scene. Her latest, Experimental Film (2015, ChiZine Press) has been scooping up awards and acclaim. As the title suggests, it’s fiction about cinema: the story of Lois Cairns, a former film critic and instructor with an autistic son, coming across the lost works of an early 20th century Canadian filmmaker whose works may resonate with supernatural power. It is a fascinating and terrifying read. I put some questions before Gemma about Experimental Film, her writing more broadly and the relationship of cinema and literature.

Murray Leeder: Experimental Film joins Walker Percy’s The Movie-goer, Theodore Roszak’s Flicker, Steve Erickson’s Zeroville and others in the peculiar category of literary fiction about cinema, and even invokes a kind of “cinematic” quality in its section headings. How do you conceive of the differences between these mediums, and is Experimental Film an attempt to bridge that difference?

Gemma Files: I'd like to start by making the point that I haven't actually read any of the cited books aside from Flicker, and I've just started reading that—I picked up a copy down at Readercon, right before I won the Shirley Jackson Award for Best Novel. So although I did read Marisha Pessl's Night Film before I started writing, most of my inspiration came from either nonfiction sources—I'm a big fan of the BFI Film Studies series in all its variations, and Danny Peary's Cult Movies trilogy of reference books—or from the one-two punch of Ramsey Campbell's absolutely amazing Ancient Images (which revolves around the search for a lost British-made Boris Karloff/Bela Lugosi movie that may have been censored for containing references to a noble family's pact with dark powers) vs. Tim Lucas's Throat Sprockets (in which a film fan becomes “infected” by the imagery of an obscure grindhouse giallo/softcore director's movies, slowly turning into a very particular sort of vampire), as well as the very detailed lecture tracks Lucas has recorded for the DVD releases of various Mario Bava movies.

As a former film critic, meanwhile, I'm always interested when people create clips of nonexistent movies for use in movies, whether as plot points or as background—it certainly seems to work better than when filmmakers try to make up writing samples for “writer” characters, especially if these extracts are supposed to prove said fictional writers' genius. (I mean, I get that the process of writing isn't very cinematic per se, but sometimes I genuinely find myself sitting there wondering if anybody associated with these films has ever written anything professionally before, or even known anyone who writes for a living.) Therefore, one of the main influences on Experimental Film is definitely “Cigarette Burns” (2005), the Season One Masters of Horror episode directed by John Carpenter, in which a legendary short film maudit from the 1970s proves to exert a violent effect not only on those who watch it but also on people who even consider watching it. I watched it again the other night and was interested to see that it suffers from dead technology syndrome (in a world of streaming and digital screenings, a world in which reel changes aren't done by hand anymore because no one's employed as a projectionist, are markers signifying a sudden impending splice even a thing?), yet remains otherwise intact and still powerful—like every film does eventually, it's already become a period piece.

As a former film critic... I'm always interested when people create clips of nonexistent movies for use in movies...

For me, the major difference between film and prose is that while film is entirely concerned with visual action and dialogue, prose can—and does—explore everything else inside of, around and behind those two things: context, memory, thoughts, feelings. You aren't restricted to what the camera “sees,” so you can examine something from multiple points of view, or reframe it through many different narrative strategies. In film, you're always balancing the camera's ability to capture events in real-time with the editor's ability to re-shape that raw footage through judicious use of cuts, dissolves, montages and other effects; this is something I've often tried to take advantage of on the page as well, the opportunity to say: “Let's just go straight from here to here, because recounting the journey between these two points adds absolutely nothing to the story.” And now there's a sort of jump-cut is definitely a phrase that's come up in more than one of my short stories before, so the way that Lois Cairns tries to either distance herself from her own experiences or “see” them more clearly by translating them into filmic/cinematographic terms is very much a continuing concern for me.

ML: Building on the above: can you imagine Experimental Film being filmed, or would that be redundant?

GF: The fact that Experimental Film has won a couple of awards has already put it on Hollywood's radar, so I've actually been recently called upon to imagine how it could be made into a film. The two biggest challenges would probably be the fact that it's chock-full of exposition which would have to be made “active” in order to engage a cinematic audience, and that it's a very interior narrative, generally: everything's about how Lois sees things, or—after a certain point—whether she sees them at all. She's also an unreliable narrator, to say the least. The stuff with her family would be difficult, as well; some readers already find her unlikeable, self-centred, obsessive, a “whiny narcissist,” as one Goodreads review put it.

Other people seem to think her son Clark's behaviour is atypical for a kid with autism (it's based on an earlier phase in my son's life, so not so much), or that her husband Simon is far too “nice” and supportive to be believable. (The latter was a conscious strategic choice on my part, by the way, because I'm really tired of horror stories in which couples under exterior pressure start emotionally cannibalizing each other, especially the magical disappearing husband/father trope—things got hard? Ooh, too bad, Daddy's gone. In my opinion, any marriage that's survived their kid being diagnosed probably isn't going to crumple just because one of them runs into professional trouble, especially if the other half of the equation sees the supernatural primarily as something God can save you from.)

ML: Your book opens with a quotation from Maxim Gorky’s 1896 “Kingdom of Shadows” essay (beginning with “Last night I was in the Kingdom of Shadows,” a review of a programme of the Lumière brothers films in Nizhni-Novgorod), albeit a slightly different translation than the one I’m most familiar with. How did you first encounter this essay and how did you react to it?

GF: I first encountered that quotation—in a much longer form—as part of a reference book about early cinema that I used to fact-check Experimental Film's first section; I used it because I thought it perfectly summed up many audiences' first reaction to cinema in execution rather than concept, and because it's frankly creepy. We have this received idea that people first exposed to the Lumiere Brothers' Train Arriving at a Platform in Paris all freaked out and ran, just like people confronted by The Great Train Robbery supposedly ducked when an actor with a gun shot it straight into the camera, and this obviously isn't entirely untrue...but neither is it untrue that people didn't take issue with the fact that real life is in colour, that it has sound. (Hell, even still photographs were sometimes in colour by the time people started putting narrative films together, and they already had wax cylinder voice recordings, though synching those up to an accompanying visual would have been a pain.)

This new technology was miraculous in one way but incomplete in others, therefore, so Gorky's reaction of finding it horrifying has that for context. This mute, grey life finally begins to disturb and depress you, he writes. It seems as though it carries a warning, fraught with a vague but sinister meaning that makes your heart grow faint. You are forgetting where you are. Strange imaginings invade your mind and your consciousness begins to wane and grow dim...

I'm also amused by the fact that he immediately leaps from the then-current “bucolic scenes of nature” and industry plus the occasional home movie (The two are so much in love, and are so charming, gay and happy, and the baby is so amusing...) to positing what he sees as an inevitable injection of sex and violence into cinematic spectacle—women undressing, “Madame at Her Bath,” even snuff. (I also could suggest a few themes for development by means of a cinematograph and for the amusement of the market place. For instance: to impale a fashionable parasite upon a picket fence, as is the way of the Turks, photograph him, then show it. It is not exactly piquant but quite edifying.) This definitely falls in line with my own observation that in much the same way that Renaissance painters often supplemented their income by charging patrons big fees to paint classical/Biblical scenes involving nudity or gore ("Portia Wounding Her Thigh" or "The Rape of Lucretia," "The Penitent Magdalene"—almost always stark naked, for some reason—or "Susannah and the Elders") that they could contemplate in private, pornographic photography was definitely a thing by that point, so it only stands to reason that roughly an hour after the first movie camera started up, somebody was probably already trying to convince people to have sex in front of it.

ML: The idea of looking back to very early cinema as a kind of space that is haunted or haunting has appears to have some currency in our contemporary world. You can see this in many of Guy Maddin’s works, including the recent web project Seances; Blumhouse Pictures is also currently doing a viral advertising campaign for a mockumentary called Fury of the Demon about an early film purported to drive viewers insane. Do you have thoughts on why this trope of early cinema’s spectrality seems of such relevance today?

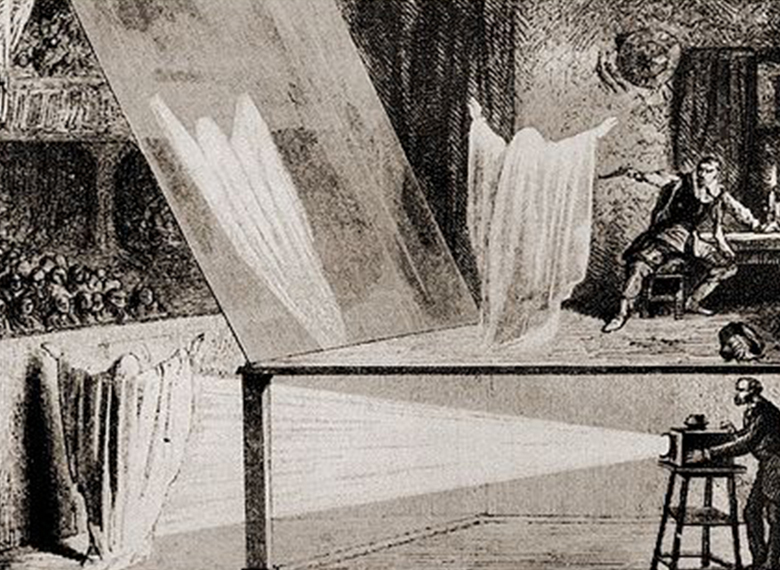

GF: I've said before that film has a sort of solidity you just don't get with almost any other medium, an irrefutable reality, which endows trick cinematography with a sort of black magic sheen. Surely that must have happened, we think, whenever we see something onscreen—and we know we're right, even if all that really “happened” was a collection of actors and/or crew members simply performing their functions for money, both in front of and behind the camera's unwavering eye. So it makes total sense that people might think of cinema as being haunted—every movie is a ghost story, housing the images of people who once lived long after their physical deaths. The starker and cruder the image is, meanwhile, the more enduring its apparent power; go back far enough, and “special effects” supposedly become a completely negotiable concept.

I've said before that film has a sort of solidity you just don't get with almost any other medium, an irrefutable reality, which endows trick cinematography with a sort of black magic sheen.

ML: Experimental Film draws on Slavic mythology, especially the Wendish legends about Lady Midday. What drew you particularly to this group of legends?

GF: I've always loved fairytales, and I knew I wanted to write a particularly creepy one for this book—something like the Grimms' “Mrs Gertrude,” a Mother Holle/Baba Yaga variant that contains one of my all-time favourite weird lines: “So now you have seen the witch in her true ornament.” Then I was clicking around, and fell headlong over a reference to Lady Midday; it was almost that simple. I liked the idea of Mrs Whitcomb drawing her inspiration from Wendish culture, because it's one of those liminal, half-forgotten things that could feed really easily into Canada's mosaic of immigrant influences. I also really love folk horror in general, so the concept of “little gods”—local gods, rural gods, supplanted and literally demonized by Christianity's influx—becoming enshrined in legend as monsters was a very attractive on. It fit in well with Safie Hewsen's Yezedi background, too, which grew in turn out of the fact that I already knew I wanted Armenian-Canadian experimental filmmaker Soraya Mousch (first introduced in “each thing I show you is a piece of my death,” my initial attempt at celluloid horror, which I co-wrote with my husband Stephen J. Barringer) to appear in the book as a supporting character.

Other attractive qualities of Lady Midday include the fact that she's the embodiment of light and heat rather than cold and darkness—we don't expect a figure with a blinding halo for a face to be horrifying, even if she's carrying a giant pair of shears. I like how she overturns our expectations about horror iconography, and I love how she represents the devouring muse, a creative impulse so pure and focussed it could cauterize your brain like sun through a magnifying glass. The more I thought about her, the more I remembered this one time I had a fever so hot I went into convulsions and felt like my mind was melting: ekstasis, “to be or stand outside oneself, a removal to elsewhere.” That was a definite little god moment. I'm attracted to that sort of numinous event or presence—it's really at the heart of why I write, and what I write.

ML: Experimental Film is also particularly interested in the effaced history of silent era female filmmakers, especially as it aligns with the history of Canadian cinema. How did you become interested in this area, and how does this interest manifest in the book?

GF: Like Lois Cairns, I used to teach both film history and Canadian film history, and I had to develop the curriculum for the latter myself, from the bottom up. So I've been obsessed for a long time with the idea that Canadians seem to have little or no regard or respect for their own cultural product, and English-speaking Canadian film is at the very bottom of that barrel. Yet when you look at the beginning of Hollywood history, so many of the founding figures of the silent screen were transplanted Canadians—Mary Pickford, Mack Sennett. The very first “movie star,” the first actor whose name became a box office draw after being revealed to the public, was Florence Lawrence, from Hamilton, Ontario. Then there were figures like Nell Shipman, “the Girl from God's Country,” who wrote, directed and produced her own movies while also doing her own stunts, training the animals she worked with, and doing one of the first-ever onscreen nude scenes. My parents are both actors, so I've been around the industry all my life, and I know how to make distinctions between runaway productions—stuff shot up here because it's cheaper, masquerading as one American city or another—and actual cultural product, let alone how ridiculously difficult it's getting to make the latter, not least because we keep scuttling our own ability to. (Check out recent modifications to the CanCon scale projects have to hit in order to get provincial/federal government funding, and weep.) Whatever I can do to attract attention to the fact that Canada is a separate country from our southwards neighbour, therefore, I'll do, so adding these sorts of observations to Experimental Film's mix was a positive pleasure.

Canadians seem to have little or no regard or respect for their own cultural product, and English-speaking Canadian film is at the very bottom of that barrel.

ML: How much of your own personal and professional experience informs the plot and characters of Experimental Film (relative, perhaps, to other writings of yours)?

GF: Oh, so much. That's probably really obvious, by this point. This is the single closest thing I've written to my own life, thus far. My Mom used to ask me why I didn't write what I knew, and I blew her off; I didn't want to produce “some damn Oprah book,” I'd tell her. But to convince people that what's patently not real maybe might be, I've gradually discovered—enough to keep them reading, at the very least—you really do have to root your fantasy in some version of emotional reality. Maybe I'm just finally old enough to give myself permission to do it this overtly.

You can find Experimental Film, along with her other publications at ChiZine Publications: www.chizine.com